Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (14 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

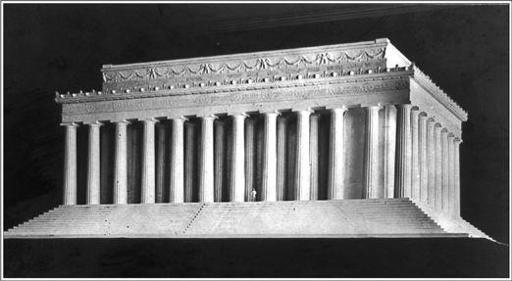

Daniel Burnham and a model of Henry Bacon’s design for the Lincoln Memorial

(photo credit 1.36)

Nineteen years after the Chicago exposition, Burnham and Millet were comrades-in-arms once again, on a project they knew was of great historic significance. Both had been young men when Lincoln was assassinated and had clear memories of the deep national grief that had ensued. For a memorial to the martyred president, Burnham had long supported a site overlooking the Potomac; he wanted the monument to be set apart from other structures and to extend the Mall, aligned to the Capitol and the Washington Monument. But Joseph Cannon, the gruff and influential former Speaker of the House known as “Uncle Joe,” was determined to keep the memorial away from “

that God-damned swamp” by the river. He favored a site across the Potomac in Arlington, Virginia, and thought that Southern members of Congress would support him. Burnham soon dispatched Frank Millet to seek out key Southern representatives and seed the notion that it would never do for the memorial to the “conquerer” to be placed on the land of the “conquered”—Arlington, after all, belonged to the sacred South.

Burnham had also asked Millet to write a report containing the Fine Arts Commission’s recommendations, and by August 10, 1911, the Memorial Commission had accepted its main points and had agreed to hire architect Henry Bacon of New York to draw up a preliminary design. Only a few weeks later, however, Joe Cannon persuaded the commission to engage architect John Russell Pope to create a competing design for two sites other than the one by the Potomac. By December both Bacon and Pope had models ready for display. Bacon’s Doric temple design had many symbolic elements and featured a statue of Lincoln inside with two chambers on either side carved with words from his Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses. The design from John Russell Pope seemed rather pedestrian by comparison—a statue of Lincoln surrounded by a double row of columns—and the proposed sites for it were not particularly distinguished.

Frank Millet returned from Rome for the decisive meeting on February 3, 1912, when the Potomac Park site had finally won the day. But “Uncle Joe” and some of his cronies were still dissatisfied and angling to change the design. So Millet no doubt took time on the

Titanic

to gird himself for his next encounter with the fractious members of the Lincoln Memorial Commission.

Daniel Burnham would not be present at that meeting. On Saturday, April 13, the architect was leaving for Europe with his wife and daughter and son-in-law for a grand tour that would run into the summer. The ship he had chosen was the

Olympic

, and after dinner on Sunday night he would think of his old friend Millet, traveling in near-identical surroundings in the opposite direction. Burnham would summon a steward and write out a Marconi message to Frank Millet on the

Titanic

. He would not receive a reply.

AT

6

P.M

. on Thursday, April 11, the sound of the

Titanic

’s bugler was heard on deck, indicating it was time for passengers to dress for dinner. The dress code had been waived on the first night at Cherbourg but from then onward “

full dress was always

en règle

” as the Washington aristocrat and amateur historian Archibald Gracie noted approvingly. For Gracie and the other first-class men, this simply meant donning white tie and tails or a tuxedo, a standard part of any traveling wardrobe. Archie Butt had slightly more sartorial choice since his seven trunks were packed with both his regular and dress uniforms along with civilian evening wear. (At the White House, Archie often changed clothes six times a day.) For this first formal evening he may have simply chosen his regular uniform or even civilian mufti, reserving a show of gold lace for later in the voyage. Most of the women, too, had a different gown packed in tissue paper for each night of the crossing but were saving their most splendid apparel for Sunday or Monday night.

The beauty of the women on board “

was a subject both of observation and admiration” according to Archibald Gracie. This display of loveliness, however, took considerable effort, making the “dressing hour” a stressful time for ladies’ maids. The array of undergarments alone would baffle a modern woman, beginning with the corsets that most upper-class women still wore. The formidable whalebone devices of the Victorian era were a thing of the past, as were the padded S-curve corsets that had pushed the bosom forward and the derrière backward in the style so favored by King Edward VII. After 1907 a longer, slimmer look was in fashion and corsets had elastic gusset inserts that were supposed to make them less constricting.

But in 1912 a rebellion against the long reign of the corset was beginning. American debutantes had adoped a “park your corset” fad that year, where the constricting undergarments were shucked and left in dressing rooms at dances and parties. Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon, had introduced a corsetless gown in her spring 1912 collection, and in the current issue of the fashion magazine

Dress

, which some first-class ladies had probably brought on board, it was noted: “

Quite as important as the more frivolous bits of underdress is the brassiere for the woman who wants to look pretty and be comfortable.”

Yet the brassiere would not find wide acceptance till after World War I, by which time the corset had finally had its day. On this spring evening in 1912, therefore, only a few of the younger, more fashion-forward women on board, such as Edith Rosenbaum or Madeleine Astor, would have dared to shed their corsets for a brassiere and chemise. Most of the first-class women were helped into their corsets by their lady’s maids, after which they stepped into the various layers of knickers and petticoats that followed. The elegant rustle of undergarments was part of the allure of a well-dressed lady in 1912, and each evening this sound was heard on the

Titanic

’s grand staircase during the procession down to dinner.

At 7:00 the ship’s bugler, a twenty-six-year-old steward named Peter Fletcher, reappeared to summon passengers to dinner with a jaunty little tune called “The Roast Beef of Old England.” By then, many passengers had already gathered in the wicker chairs of the Palm Room. On the second evening at sea there was a convivial, settled air on board, with table companionships well established and stewards addressing their clientele by name. Contrary to popular belief, there was no “captain’s table” where E. J. Smith would entertain a favored selection of passengers each night. Smith normally took his meals at a table for six in the dining saloon or in his cabin, served by his valet or “tiger” as the captain’s attendant was known.

Entertaining duties largely fell to Chief Purser Hugh McElroy, whose Irish wit and genial table talk made him well suited to the task. Passengers dining alone were usually assigned to the purser’s table, and McElroy would then invite two additional passengers to round out the company each evening. W. T. Stead was asked to join McElroy’s table one night, as was his dining companion Frederic K. Seward, who later recalled that all present were “

almost spell-bound by the humor, and beauty, and breadth of vision of Stead’s conversation.” At one point on the voyage Seward was taken aside by an English passenger who whispered in his ear regarding Stead, “

My dear fellow, you know that he was a pro-Boer?” Opposition to the Boer War in South Africa had indeed been one of Stead’s contentious causes—in 1899 he had penned a pamphlet entitled “Shall I Slay My Brother Boer?”

It is not known whether W. T. Stead and Frank Millet spent time together on the

Titanic

, though the pairing of two such celebrated raconteurs would have made for a lively colloquy. The ubiquitous Mark Twain was a friend in common—Stead had met him aboard ship in 1894 while returning from his first visit to America. (By coincidence, Stead’s ship on this crossing had been the

New York

, the same liner that had swung into the

Titanic

’s path while she was leaving Southampton.) During a storm at sea, Stead had kept Twain distracted by recounting one of his celebrated ghost stories. The two men had corresponded afterward, and exchanges of opinion between them had appeared in the

Review of Reviews

, the monthly journal Stead founded in 1890 after leaving the

Pall Mall Gazette

. On the same crossing, Stead had also met and befriended one of Millet’s closest friends, Charles Francis Adams, a Back Bay aristocrat and descendant of the two Adams presidents, and brother of the Washington writer and diarist Henry Adams.

Given these connections, it’s likely that Frank Millet at least greeted W. T. Stead on the

Titanic

, though he may have been wary of the old newsman’s reputation for spooks and séances. Millet might also have taken a dim view of

If Christ Came to Chicago

, the book Stead wrote after his trip to the 1893 exposition. Stead had been fascinated by Chicago and had spent several months there interviewing criminals, gamblers, corrupt politicians, and prostitutes and then describing the city’s underbelly from a viewpoint leavened with his unique brand of Christianity. When published in late 1894,

If Christ Came to Chicago

caused a considerable stir. It opened with an illustration of Christ casting out the moneychangers in front of the White City’s central Court of Honor, and in its back pages was a color-coded foldout chart of Chicago’s red-light district, locating all the brothels, saloons, and pawnbrokers to be found there. By unintentionally providing a handy guide to Sin City, the book became an instant bestseller.

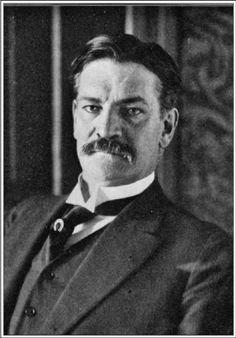

Archibald Gracie

(photo credit 1.16)

As Millet, Archie Butt, and Clarence Moore passed through the dining saloon that Thursday evening, a likely table to have received friendly greetings was the one occupied by Colonel Archibald Gracie IV and his two companions, Edward Austin Kent, a Buffalo architect, and a New York clubman named James Clinch Smith. The affable Gracie was the most outgoing of the three and had the polished manners of a man from an old and distinguished family. His great-grandfather, Archibald Gracie I, was a Scottish-born shipping magnate who in 1799 had built a large Federal-style home in Manhattan overlooking the East River that is now known as Gracie Mansion, the official residence of the mayor of New York.

By the time Archibald Gracie IV was born in 1859, the family was living in Mobile, Alabama, where his grandfather had established a cotton brokerage business. When the Civil War broke out, Gracie’s father, Archibald Gracie III, enlisted in an Alabama regiment, eventually becoming a Confederate brigadier general before being killed during the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, in 1864. Losing him at the age of five had left Archibald Gracie IV with a great curiosity regarding his father’s life and Civil War service. With him on the

Titanic

were copies of

The Truth About Chickamauga

, his 462-page account of the 1863 battle in which his father had served. Like many Civil War battles, Chickamauga was a bloodbath, second only in carnage to Gettysburg—a victory for the Confederate side though a Pyrrhic one. Researching Chickamauga had exhausted Gracie. As he would later write in

The Truth About the Titanic

, “

It was to gain a much needed rest after seven years of work thereon, and in order to get it off my mind, that I had taken this trip across the ocean and back. As a counter-irritant, my experience was a dose which was highly efficacious.”