Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (2 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

In America, the

Titanic

is often described as a cross-section of the Gilded Age, an era of rapid industrialization and wealth creation in the United States that began in the 1870s and ended with the introduction of income taxes in 1913 and the outbreak of World War I the following year. Her sinking is sometimes viewed as the warning bell for a complacent society steaming toward catastrophe in the trenches of the Western Front. As the poet and actress Blanche Oelrichs observed, it was “

as if some great stage manager planned that there should be a minor warning, a flash of horror” before the greater calamity to come.

When Robert Ballard’s book

The Discovery of the Titanic

was nearing publication in 1987, I asked Walter Lord, the dean of

Titanic

historians, to pen an introduction. In it he pondered the enduring mystique of the

Titanic

and concluded:

The thought occurs that the

Titanic

is the perfect example of something we can all relate to: the progression of almost any tragedy in our lives from initial disbelief to growing uneasiness to final, total awareness. We are all familiar with this sequence and we watch it unfold again and again on the

Titanic

—always in slow motion.

As the tragedy of the

Titanic

unfolds once again on these pages, the remarkable characters who people it, will, I trust, help illuminate a world both distant and near to our own, and convey anew the poignance of this epochal disaster.

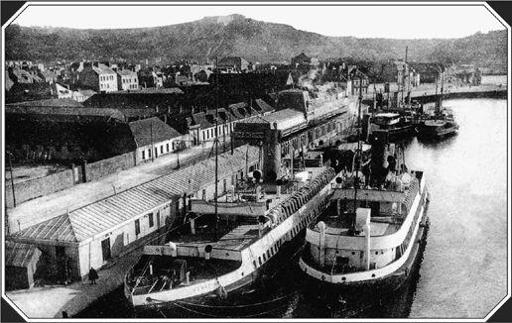

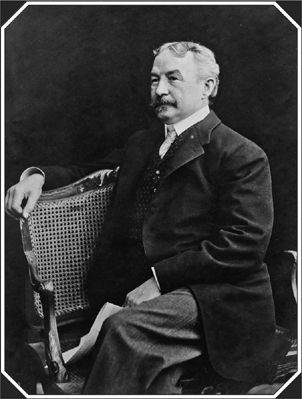

The train from Paris pulled in behind Cherbourg’s dockside station on the afternoon of April 10, 1912. On board was the well-known artist and writer Francis D. Millet.

(photo credit 1.1)

T

he

Titanic

was going to be late.

To the first-class travelers aboard the

Train Transatlantique

, now chugging to a stop at Cherbourg’s quayside terminus, this would be dismaying news. The six-hour journey from Paris had been quite long enough. How many hours, they wondered, would now have to be spent in this small, smoke-grimed station before White Star’s new steamer could arrive to take them to New York?

As the passengers descended from the train, the scene on the platform was frenetic, according to a young American named R. Norris Williams, who recalled “

the porters scurrying around, the crowding and jostling … excited people with lost luggage, porters asking for a larger

pourboire

, Thomas Cook’s representatives trying to placate some irate would-be-important-looking person—in short—pandemonium.”

One representative trying to placate amid the pandemonium was Nicholas Martin, the manager of White Star’s Paris office, who had taken the train to Cherbourg to be a calming presence for just this kind of circumstance. As trolleys piled high with steamer trunks and leather suitcases were pushed along the platform, he circulated among knots of passengers, offering reassurances that although the

Titanic

had been delayed while leaving Southampton, she was now en route across the Channel and the tenders would be ready for embarkation by half-past five.

The most important person Martin had to appease was a tall, thin man with a large black mustache and an impatient expression. The American millionaire John Jacob Astor IV was not only the wealthiest passenger waiting to board the

Titanic

, he was also a friend of the White Star Line’s chairman, J. Bruce Ismay. Astor and his young wife, Madeleine, had, in fact, made the crossing from New York with Ismay on the

Titanic

’s sister liner,

Olympic

, just ten weeks before. Astor, according to one acquaintance, “

made a god of punctuality” and had a habit of compulsively reaching into his waistcoat to check the time on his gold pocket watch. Fueling Astor’s impatience on this occasion was the uncertain health of his wife, now several months pregnant. Concern for her had caused him to hire a nurse to be in attendance for the voyage home. Martin no doubt made sure that the Astor party, which included the nurse, a lady’s maid, a valet, and an Airedale terrier, was quickly ushered into the station.

Far less demanding of the White Star manager’s attentions were the more than one hundred third-class passengers, Lebanese and Syrian emigrants, mostly, along with a few Croatians and Bulgarians, who were arranging themselves docilely on wooden benches beside their wicker cases and carpetbags, occasionally calling out to their playing children to stay near. They had been traveling for days since they had left their villages, and a few hours more made little difference.

To a seasoned traveler like the celebrated artist and writer Frank Millet, delays, likewise, were something to be taken in stride. But spending several hours in a stuffy waiting room amid the braying voices of his fellow Americans was a more daunting prospect. Like many U.S. expatriates, Millet had an acquired disdain for his less sophisticated countrymen—and women. “

Obnoxious, ostentatious American women,” in fact, would be singled out for special scorn in a letter he penned the next morning from the

Titanic

. “[They are] the scourge of any place they infest and worse on shipboard than anywhere,” he wrote to his old friend Alfred Parsons. “Many of them carry tiny dogs and lead husbands around like pet lambs. I tell you, when she starts out, the American woman is a buster. She should be put in a harem and kept there.”

Such crankiness was not typical of Frank Millet, a man known for his geniality and disarming smile. His friend Mark Twain used “a Millet” as a label for a warm and likeable fellow. “

Millet,” he once wrote, “makes all men fall in love with him” and is “the cause of lovable qualities in people.” Millet’s less than lovable mood on this April day in Cherbourg can be put down to exhaustion. He had just completed a month in Rome where, as he described to Parsons, he had had “the Devil of a time.” As the head of the new American Academy of Art in the Eternal City, Millet had found himself mediating a stream of administrative squabbles. And his final week there had been monopolized by paying court to J. Pierpont Morgan, the American financier who was to help fund the Academy’s new building.

Now Millet was required back in America where more meetings awaited. In Washington, the Commission of Fine Arts, for which he was vice chair, was eager to finalize agreement on a Doric temple design for the Lincoln Memorial. Next came the American Academy’s annual board meeting in New York followed by a trip to Madison, Wisconsin, where he had won a commission to paint murals for the state capitol building. It was a punishing schedule for a man who would be sixty-six in November but Frank Millet had never been content doing just one thing. As one of his oldest friends observed, “

Millet was an artist but constantly subject to a great temptation, that of making excursions into other fields. Thus he led more or less the life of a wanderer.”

During his wandering life Millet had shown an almost uncanny knack for being present at many of the landmark occurrences of his day. Where things were happening, Millet was invariably to be found—from the U.S. Civil War, where he had served as a drummer boy, to the building of the White City for the 1893 Chicago Exposition, to the conflict in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, to the boarding of the

Titanic

on its maiden voyage. As an English art critic wryly noted in 1894, “

Inertia is not one of Millet’s faults; he is ever in movement, a comrade in the world of art. Are the heavens to be decorated? See Millet. Is there to be a banquet for the gods? See Millet. Has the army moved? Yes, and Millet with it. He breathes the air of two hemispheres … he is contagious in art and manly enthusiasm.”

The name by which Millet’s era is known was coined by his friend Mark Twain in his first novel,

The Gilded Age

, a satire he cowrote with a friend in 1873, on the greed and corruption underlying Americas’s post–Civil War boom. On March 11, 1879, Twain had stood beside Millet at his wedding in the Montmartre

mairie

[town hall]. The other witness was sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and the bride was Elizabeth “Lily” Merrill, the younger sister of one of Frank’s Harvard classmates. Lily was a beautiful, if strong-minded, young American woman—drawn from the very ranks of those whom her husband would later claim “should be put in a harem and kept there.”

In 1885 Lily and Frank became the center of an artists’ colony in the village of Broadway in Worcestershire. This unspoiled Cotswold village had beguiled Frank on a visit from London in the spring of that year and he had rented an old stone house on the village green. His artist friends came to visit and some chose to stay. Henry James put Broadway on the map by extolling it in

Harper’s Monthly

as “

this perfection of a village.” The novelist, then forty-two, had been drawn there by the presence of one of his protegés, a twenty-nine-year-old artist with soulful eyes and a cropped black beard named John Singer Sargent. In 1886 Sargent painted a portrait of Lily Millet looking ravishing in a white dress and mauve shawl with her black hair swept high. Twenty-six years later she still wore her hair that way, though it had by then turned an elegant white.

In April of 1912, Frank, too, showed signs of his years and his once-handsome face had assumed the mien of a genial owl. As he walked through the tiled concourse of Cherbourg’s dockside station, his features likely also reflected the fatigue he felt after his challenging month in Rome. Lily had joined him toward the end of his time there, and they had left together for Paris two days ago and stayed at the Grand Hotel before departing on separate trains. By now Lily would be across the Channel and on her way back to Broadway, to Russell House, the large stone manse where, years before, his circle of artistic friends—Sargent, James, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edwin Austin Abbey, Edmund Gosse, Alfred Parsons, and others—had enjoyed rollicking evenings of what Frank called “high Broadway cockalorum.”

In recent years, however, Russell House had been more home base than home for Millet. It had really been Lily’s home, where she had raised his daughter and two sons, decorated the house, and designed the large gardens. Millet’s absences most often took him to the United States, where his murals of mythical and historical figures were well suited to the rotundas of the domed and pillared public buildings going up in the burgeoning capitals of his homeland.

America’s fondness for grandiose neoclassicism would reach its apotheosis at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Around a large boat basin where Venetian gondolas would glide was erected the White City, a staggering display of domes, porticos, colonnades, and loggias all covered in a white finish and lit at night by white electric bulbs. Frank Millet was the man who made the White City white. As the exposition’s director of decorations he had come up with the right mix of paint to cover the rough, temporary finishes of the pavilions. To help his “Whitewash Gang” apply it within a very tight schedule, he had even invented an early form of spray painting, using a compressor and a hose with a nozzle fashioned from a gas pipe. Millet also created murals for the New York State pavilion and painted some large winged figures on the ceiling of the Palace of Fine Arts, which housed the largest exhibition of American art ever seen in the United States.