gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (42 page)

What was it that led the Reverend Marmaduke Carver to conclude that the primordial fountain that gave rise to the four rivers of Paradise existed in the same mountain range as Abus Mons, in other words Bingöl Mountain? Was he aware of Strabo’s reference to Abus Mons as the source of both the Euphrates and Araxes?

33

It is possible, although if this were the case then surely he would have mentioned it. More likely is that it was quite simply an intuitive decision based on whatever evidence he had in hand when he came to write his fascinating book.

Strangely, Carver does not identify the Gihon with the Araxes, nor does he associate the Greater Zab with the Pison. Instead, he sees major waterways that split away from the Tigris and Euphrates as evidence for the existence of these other two rivers. The Pison, for instance, he has entering neighboring Persia and linking, eventually, to the Indus, one of the longest rivers in Asia. Yet this vagueness should not detract from Carver’s remarkable insights into the geographical location of the Garden of Eden, and we are by no means finished with his findings quite yet.

I felt the need now to focus my efforts more toward Bingöl Mountain, the Abus Mons of antiquity, in an attempt to better understand why Carver believed that here somewhere was the primordial fountain of life, and why the Dutch scholar Martijn Houtsma concluded that this was “the site of the biblical Paradise.”

29

THE WORLD’S SUMMIT

B

ingöl is a Turkish place-name that means “a thousand (

bin

) lakes or springs (

göl

),” an allusion to the many mountain streams that take their rise from the glacial lakes that grace its summit. In the Armenian language, Bingöl Mountain is known as Biurakn, which means “a million (

bir, byur

) eyes (

akn

),” a reference, once again, to the countless springs, or “eyes,” that take their rise on its summit (although see chapter 33 for a clearer interpretation of this Armenian name).

Bingöl is mentioned also in Armenian texts under the more enigmatic name of Mount Srmantz, or Srmanç

1

(again, see chapter 33 for a discussion of the meaning of this name), described as Katar Erkri, the Summit of the Earth,

2

or the World’s Summit,

3

or, indeed, the Top of the World, from which flowed the “four rivers to the four corners of the world.”

4

Bingöl was also a “place of the gods,”

5

the habitation of mythical beings identified, almost certainly, with the Peri of Kurdish and Persian folklore (the region’s population until the early twentieth century were mainly Armenians, Kurds, Turks, Yezidi, and Kızılbaş [Alevi], the last two being ethno-religious groups quite separate from the others mentioned here).

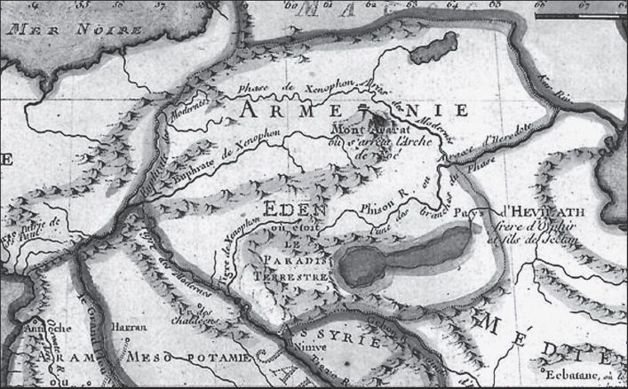

Very probably, the Judeo-Christian belief in the four rivers of Paradise flowing out of the Garden of Eden (see figure 29.1, for instance) is simply a variation of the cosmic mountain theme preserved in connection with Bingöl Mountain by the Armenian inhabitants of the region. It was probably for this reason that Martijn Houtsma, in 1927, noted that Armenians considered it “the site of the biblical Paradise,”

6

which, if correct, should be extended southward to include the plain of Mush, the proposed site of the Garden of Eden itself.

Figure 29.1. Section of a map of the Middle East by French cartographer and geographer Philippe Buache (1700–1773), published in 1783. Eden is shown to the west of Lake Van, placing it in the vicinity of the Mush Plain and Armenian Highlands. Confusingly, the identities of the Pison and Gihon rivers are transposed: the Araxes is shown as the Pison (written “Phison”), while the Greater Zab becomes the Gihon (written “Gehon”).

Having said this, we know that the Genesis account of the earthly Paradise describes real rivers, three of which—the Tigris, Euphrates, and Araxes—were considered to take their rise from the same primordial fountain that existed somewhere in the vicinity of the Bingöl massif. Only one of the rivers, the Pison, remains somewhat of an enigma, even though the Assyrian Church, as we saw in chapter 27, identifies it with the Greater Zab, which rises in the mountains southeast of Lake Van.

THE PISON RIVER—NEW EVIDENCE

Having said this, compelling evidence suggests that the Pison was also once seen to take its rise on Bingöl Mountain and is to be identified with the Peri Şu, or Gail River. This flows initially westward before turning south to merge, eventually, with the Eastern Euphrates just north of the ancient fortress town of Kharput, thought to be Carcathiocerta, the lost capital of Sophene.

This connection between the Pison River and the Peri Şu is recorded in a book written in 1870 by German cartographers Wilhelm Strecker and Heinrich Kiepert.

7

It examines the geography of the

Anabasis,

a seven-volume work penned by Greek professional soldier and writer Xenophon (ca. 430–354 BC). He marched with the ten thousand Greek mercenaries hired by Cyrus the Younger, who sought to wrest the throne of Persia from his brother, the king, Artaxerxes II.

8

The route of the Ten Thousand, as they are known, to and from the Battle of Cunaxa on the banks of the Euphrates, some 45 miles (72 kilometers) north of Babylon, took them through Colchis (modern Georgia), Armenia, and Mesopotamia. The identity of the rivers, towns, and cities Xenophon describes encountering on this two-way journey has been the subject of debate among scholars for hundreds of years.

The Ten Thousand are known to have marched through the foothills of the Bingöl massif, and discussing the sights they might have encountered Streker and Kiepert make the following observation:

The native people spoken to on my trips to Armenia Major, call this river [i.e., the Peri Şu] Phison, and see it as a river of Paradise, [which they say] lies on Bingöl Mountain.

1

That this is not an arbitrary adoption of modern times is proved by the ancient Armenian writer who indicates the existence of a Castell Phison in Sophene, probably identical with the area between the two Euphrates.

9

The superscript number 1 after the word “Mountain” in the original text refers the reader to the base of the page. Here we read that although the inhabitants of the region assert the Peri Şu to be the “Phison,” the authors have been unable to verify this claim among the works of the Armenian writers.

10

This is a shame. Yet we are still left with the tantalizing possibility that the Peri Şu

is

the Pison, even though this new information is unlikely to constitute a major challenge to the Greater Zab’s claim to being the self-same river. As stated in chapter 27, the word of the ancient Assyrian Church should not be taken lightly, especially as the Armenian Church seems to have a tendency to move around holy places (the case of the ark’s Place of Descent being a prime example—see chapter 30).

Having said this, the fact that the Armenian population of Armenia Major

believed

that the Peri Şu was the Pison now links the sources of

all four

rivers of Paradise with the area around Bingöl Mountain, which, we should not forget, was known in Armenian tradition as Katar Erkri, the Summit of the Earth, its waters carrying the “four rivers to the four corners of the world.”

*17

11

FOUNTAIN OF LIFE

Quite independent of Judeo-Christian tradition, Muslim Kurds revere Bingöl Mountain as the site of another heavenly, paradisiacal fountain of great renown. Here is to be found Ma’ul Hayat, the Fountain of Life, the waters of which can rejuvenate youth and provide everlasting life.

12

According to popular legend, Alexander the Great (called in Persian Iskender and in Turkish Zülkarneyn, meaning “the Horned One” or “the Two-horned,” a reference to the ram horns on his helmet) traveled to “the land of darkness,” beyond the setting sun, in search of the Fountain of Life, which was said to exist “in the north, beneath the Pole Star.”

13

His guide and vizier on the journey was the mysterious al-Khidr, a wise man; however, when they came to a fork in the road, both men went in different directions. Only al-Khidr ended up finding the Fountain of Life and drinking from its waters (or eating a fish that swims in the fountain in another version; see figure 29.2). Even though al-Khidr waited for Alexander to catch up, the fountain disappeared as he approached. Al-Khidr also then vanished, having been granted immortality by Allah.

Although the Persian and Turkish accounts of Alexander’s journey do not mention Bingöl by name, local Kurdish folklore does. Its version of the story tells how Alexander, with deep wounds and pains in his body, went in search of the Ab’i Hayat, the Waters of Life, which he found in the vicinity of Bingöl Mountain (named Jabal-i-çur). Here he either drinks or bathes in its waters, an act that cures his ailments. In honor of this miracle Alexander chooses a spot on a nearby river and builds a castle called Çapakçur,

14

this being the old name for the town of Bingöl, which lies a short distance from the mountain.

Figure 29.2. Al-Khidr (Turkish Hızır), the Green One, who gains immortality at the Ma’ul Hayat,

the Fountain of Life

, thought to be located in the vicinity of Bingöl Mountain.

AL-KHIDR, THE GREEN ONE

Al-Khidr, called in Turkish Hızır, means the “Green One.” He features in the Holy Qur’an,

15

as well as in Persian literature and various non-Islamic sources, as a mysterious figure, an ever-youthful “servant of Allah” who appears at the right moment to avert a disaster or rectify a fatalistic situation. There are many accounts of people who encounter a bearded holy figure only to find afterward that it was al-Khidr. He is a saint and a holy man, as well as the spiritual head of the Sufi movement, the so-called

qutb,

the intermediary between Allah and humankind. He is also identified with Saint George and shares the same feast date as him, which is April 23. Some even see the presence of al-Khidr in the proliferation of carved foliate heads, or Green Men, in Norman churches and cathedrals.

16

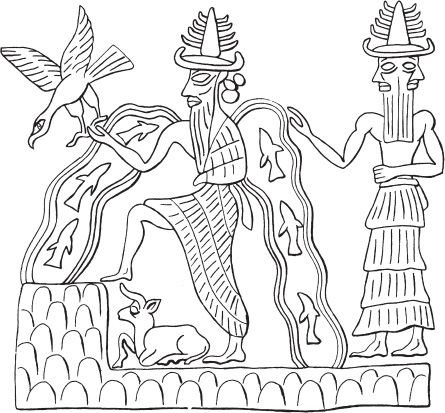

THE CULT OF ENKI

Al-Khidr himself was originally, most probably, a deity belonging to Mesopotamian myth and legend. Very likely he is linked with Enki, the Sumerian god of creation, water, and intelligence, known in the Akkadian and Babylonian language as Ea. In art Enki is generally shown as a human figure wearing a horned helmet with streams of water emerging from his shoulders, like twin fountains (see figure 29.3). Within the flow fish swim upstream, like salmon trying to reach the source of a river. These twin streams represent the Tigris and Euphrates,

17

over which Enki presided as god of Eridu, an ancient Mesopotamian city located on the shores of the Shatt al-Arab waterway, where the two rivers come together before emptying into the Persian Gulf. However, there is no reason why Enki should not also have been connected with the

sources

of these mighty rivers.