gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (40 page)

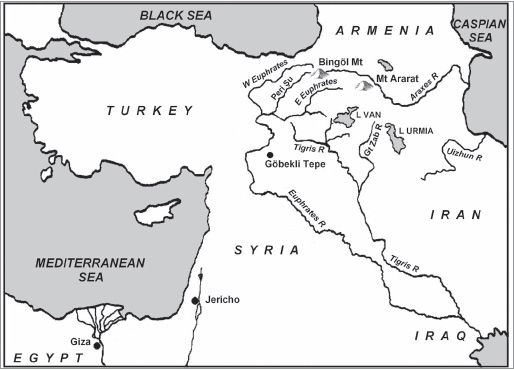

Figure 27.2. Map of southwest Asia showing the most likely candidates for the four rivers of Paradise: the Euphrates (Phrat), Tigris (Hiddekel), Araxes (Gihon), and Greater Zab (Pison). The modern trend in identifying the Pison with the Uizhun River of Iran is rife with problems due to its great distance from the sources of the other three rivers.

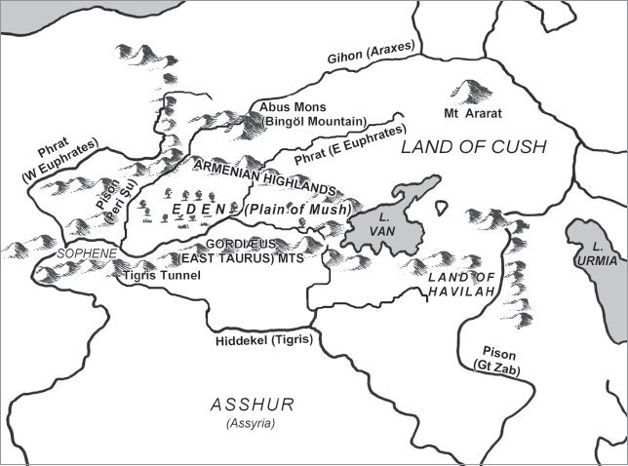

Choosing the Phasis as the Pison pulls the imaginary epicenter for the terrestrial Paradise much farther north, toward the northern extremes of the Armenian Highlands, whereas identifying the Pison with the Greater Zab places the epicenter much farther south, close to the northern edge of the plain of Mush, which separates the Armenian Highlands from the Eastern Taurus Mountains to the south (see figure 27.3).

Figure 27.3. Map showing sources of the four rivers of Paradise with their epicenter in the vicinity of the Mush Plain in eastern Turkey. Note the locations of the land of Cush, through which the Gihon flowed, and the land of Havilah, associated with the Pison River. Note also the Peri S̨u, or Gail (“Wolf”) River, which in Armenian tradition is identified with the Pison (see chapter 29).

Was this where I would find the Armenian monastery where, according to my dream, the monks believed they served God in the Garden of Eden itself? As we shall see next, the Mush Plain becomes one of the most likely candidates for the site of the terrestrial Paradise, information that, although available long ago, has not stopped theologians and scholars from locating Eden everywhere but where the four rivers of Paradise take their rise.

28

THE FOUNTAIN OF PARADISE

T

he book of Genesis’s description of the four rivers of Paradise indicates very strongly that the Garden of Eden was located in historical Armenia, modern-day eastern Turkey, with the epicenter being somewhere in the vicinity of the enigmatic plain of Mush, a vast expanse of congealed lava, created across tens of thousands of years by the outpouring of the various volcanoes that surround it. After crumbling to dust, the lava was transformed into a rich soil that has made Mush one of the most fertile regions in eastern Turkey, noted in the past for its wheat and tobacco. Vineyards were also once numerous, with a fair wine apparently being produced.

1

THE PLAIN OF MUSH

The plain itself lies at a height of just over 4,100 feet (1,250 meters) above sea level and is approximately 40 miles (64 kilometers) in length from east to west and 10 miles (16 kilometers) broad. Visible at its eastern end is the extinct volcano Nemrut Dağ (Mount Nimrod), which takes the form of a gigantic caldera half a mile (800 meters) in diameter, within which is an enormous crescent-shaped lake. Obsidian from Nemrut Dağ has been found at Göbekli Tepe.

The Murad Şu, or Eastern Euphrates, cuts right across the plain, dividing it in two, before vanishing into a narrow gorge at its western end. This creates a pass through the Eastern Taurus Mountains, along which the somewhat hazardous road to Diyarbakır winds its way. This was the old obsidian route from Bingöl and Lake Van to the various proto-Neolithic and Pre-Pottery Neolithic centers, such as Hallan Çemi, Çayönü, Nevalı Çori, and, of course, Göbekli Tepe.

Another gorge at the plain’s southeast corner forms a pass through the Eastern Taurus range, providing access to the university city of Bitlis (ancient Baghesh) and Lake Van while another pass, carved out by the Murad Şu, opens the way north toward Bingöl, both the town and the mountain, beyond which is the old Armenian city of Karin, modern-day Erzurum.

MONASTIC FOUNDATIONS

Some miles to the northwest of the town of Mush, the capital of the province of the same name, are the remains of Surb Karapet, or more correctly Surb Hovhannes Karapet Vank, the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist. Before its destruction at the time of the Armenian Genocide in 1915, it was a major place of pilgrimage, with Christians coming here from all over Armenia to venerate holy relics belonging to John the Baptist. According to tradition, Armenia’s great crusading churchman Gregory the Illuminator built the monastery on the site of important pagan temples destroyed by him and his army at the beginning of the fourth century. Today, Surb Karapet, which from old pictures looks more like a fairy-tale castle than a monastery, is little more than a few pathetic walls in the middle of a bustling Kurdish village, which has long since lost interest in its rich Armenian heritage.

Apparently, several monasteries were once to be found on the plain of Mush, which formed part of a royal kingdom called Taron, or Turuberan, where Armenian Christianity had its beginnings even before the arrival of Gregory the Illuminator in the fourth century.

2

I could find information about just one other notable monastic ruin in the area, and this was Surb Arakelots (Holy Apostles), located in a mountain valley southeast of the town of Mush. However, an examination of what was known about Surb Karapet and Surb Arakelots, or, indeed, any of the other monasteries that once existed in the region, did not in any way feel similar to what I had seen and experienced in my dream.

THE TREE OF LIFE

Yet the more I recalled the strange ceremony taking place inside the gloomy church interior, the more I became convinced not only that the Eden monastery existed, but that the monks there had been elevating an object of great spiritual value. It had been removed from a plain, wooden box that acted as a reliquary (a relic holder). As to the nature of the relic, this seemed to be a blackened piece of wood, like a short, round section of a tree branch, some 2.5 inches (6 centimeters) in diameter and 7 to 8 inches (18 to 20 centimeters) in length.

Initially, I thought the monks might have identified this relic as a piece of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which the Genesis account tells us was to be found in the Garden of Eden. However, this did not sit right with me, and very quickly I realized that I had this wrong. The relic was in fact thought to be a fragment of the Tree of Life, the

other

tree in the Garden of Eden. That felt absolutely right, especially as I had seen it being elevated during a ritual that seemed to celebrate life itself.

The monks, I suspected, believed that simply possessing this holy relic invoked a sense of the eternal life that Adam and Eve experienced before their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The couple’s existence was sustained through their proximity to the Tree of Life, which, situated within the garden, was seen as a powerhouse of divine energy that transcended the normal laws of nature. Yet without the benefits of the Tree of Life, Adam and Eve, along with all their descendants, were doomed to suffer mortality in all its ugly ways, a just punishment for committing the original sin, or so the book of Genesis tells us.

That the monks of the monastery drew some kind of spiritual power from what they saw as a fragment of the Tree of Life made absolute sense. Combining the religious potency of this relic with the fact that the monastery was thought to have existed in the Garden of Eden would only have increased their faith in what they believed they were achieving here in this spiritual powerhouse. No wonder I could so vividly recall this archaic ritual that must have taken place before the assumed destruction of the monastery at the time of the Armenian Genocide.

I sensed strongly that the monastery in question existed somewhere in the vicinity of the plain of Mush. It was a perfect setting for the Garden of Eden, especially as high mountains surround it on all sides and from these come streams that feed all four rivers of Paradise.

FINDING OTHER EDENS

Despite this information, the most often quoted solution regarding the whereabouts of the Garden of Eden stems from the somewhat puzzling conclusion, first proposed by influential French theologian and pastor John Calvin (1509–1564), that the terrestrial Paradise was located in the vicinity of Basrah, in southern Iraq. Here the Euphrates and Tigris rivers were once thought to have come together and then parted again to form all four rivers of Paradise. The fact of the matter is that although these two great rivers do indeed converge here to form the Shatt al-Arab waterway, into which flows Iran’s Karun River (which some take to be the Gihon

3

), this hardly fits the evidence offered for the location of the Garden of Eden in the book of Genesis.

Others have suggested that the four “heads” of the rivers of Paradise refer to their mouths, meaning that we should be looking for the Garden of Eden where the Euphrates and Tigris empty into the Persian Gulf. This has prompted all sorts of complicated theories involving now-vanished rivers, with the most persuasive being that the Pison once ran through Arabia’s Wadi al-Rummah, emptying into the Persian Gulf close to the Shatt al-Arab waterway.

4

As far-fetched as these claims might seem, they remain the most popular theories regarding the true site of the Garden of Eden.

5

More incredible still is the view that the holy city of Jerusalem is the terrestrial Paradise, based on a few brief references in the Old Testament comparing the city to the Garden of Eden, along with a Jewish legend that speaks of Jerusalem as the center of the world.

6

Once again, this is not simply the belief of lay people, but the opinion of theologians and historians, even though Jerusalem is located nowhere near

any

of the easily identifiable rivers of Paradise.

These theories have been put forth despite the fact that Armenian scholars have for many years attempted to convince the outside world that the terrestrial Paradise was located in their historical homeland. Their arguments go unnoticed because they are usually written in Russian Armenian, which very few non-Armenians can read. Even when their work

is

published in English, something is lost in translation, resulting in very few people taking it seriously.

7

THE REVEREND MARMADUKE CARVER

Yet, as we have seen, Westerners do occasionally conclude that the area around the

sources

of the four rivers of Paradise constitutes the most likely site of the Garden of Eden. Dutch scholar Hadrian Reland worked this out at the beginning of the eighteenth century, although he was certainly not the first to do so. One of the earliest individuals to come to the same conclusion was the rather grandly named Marmaduke Carver (d. 1665), a former rector of Harthill in South Yorkshire. His fascinating work on the subject, entitled

A Discourse of the Terrestrial Paradise, Aiming at a More Probable Discovery of the True Situation of That Happy Place of Our First Parents Habitation,

was published posthumously in 1666, one year after his death.

Having learned that the Reverend Marmaduke Carver had identified the site of the Garden of Eden as Armenia Major, I decided to find out more about the churchman’s life and theories, so went in search of him and his book, beginning with his former parish of Harthill, near Sheffield. Yet here, in the local parish church, I found no mention of him, other than his name entered in a long list of rectors from medieval times to the present day.

One thing I did manage to establish was that toward the end of his life Carver had spent much of his time in the city of York, just 60 miles (97 kilometers) from Harthill. Here he had become chaplain to Sir Thomas Osborne (afterward Duke of Leeds), high sheriff of the county, delivering sermons in York Minster, the city’s famous cathedral. More significantly, I found that on his death in August 1665 Carver’s body had been laid to rest in the south aisle of the cathedral choir.

So after leaving Harthill, I traveled to York Minster, hoping to find some evidence of Carver’s gravesite. Yet no evidence of his interment remains today, not even the wall plaque that marked the spot. This was obviously a great disappointment, so after sitting down briefly in the choir area to meditate on what I should do next, I made the decision to visit the York Minster Library, located within the cathedral grounds. Here I was finally able to find out a little more about the fate of Marmaduke Carver’s memorial plaque. Originally it had borne an inscription in Latin, written by James Torre, an early historian of the minster, but this had been destroyed during restoration work in 1736. It was subsequently replaced with a new plaque, its inscription now in English. This, however, along with the site of Carver’s grave, has since been lost due to subsequent restoration work in the south aisle. Mercifully, both versions of the inscription have been preserved.

*16

8

As you can see, it is a fitting epitaph to the churchman’s life and work, in particular his search for the terrestrial Paradise: