Hearts West (13 page)

Authors: Chris Enss

With the help of her good friend, Georgiana Bruce Kirby, the two built a ranch house on the property and began farming the land. Realizing their long, full dresses hampered their work in the fields, Eliza decided the two needed to wear bloomers. She made their wide, loose pants from old gymnastic suits. Like her mail-order bride plan, it was another unconventional action that shocked the community around her.

In 1852, Eliza accepted a marriage proposal from San Francisco resident and entrepreneur, William Alexander Fitzpatrick. According to Georgiana's journal, William was the “greatest blackguard in the country.” He frequently mistreated Eliza and their life was a series of stormy partings and reconciliations. The two divorced four years later.

In 1856, Eliza abandoned ranch life and returned to her work at state women's prisons, speaking out for reform. She eventually took a job as principal of the first Santa Cruz public school. In her leisure time she toured the state, lecturing on topics ranging from spiritualism to women's rights. She penned four books on the subject of women and the emerging West. In 1859, she organized a society to assist destitute women in finding homes in the West, and took charge of several such emigrant parties. “None but the pure and strong-hearted of my sex should come alone to this land,” she reasoned.

Historian Herbert Bancroft boasted that Eliza was one of the “first women to recognize the effects her sex could have on the Wild Westâand probably one to be avoided at all costs by the hell-raising male population in the California gold fields.” Her efforts convinced like-minded female pioneers to relocate and cast their influence over the new frontier.

This is the most gladdening intelligence of the day . . . Eliza Farnham and her girls are coming, and the dawning of brighter days for our golden land is even now perceptible. The day of regeneration is nigh on hand . . . We shall . . . prepare ourselves to witness the great change which is shortly to follow, with feelings akin to hilarious joy.

California Daily Altaâ1849

Eliza Farnham's unconventional methods of bringing civility to the Wild West helped transform the frontier and make the emerging country fit for wives and family.

BRIDAL COUPLES

D

uring the late 1880s, Gold Country hostelries were literally filled with blushing brides. Women arrived from eastern locations to wed the men they'd met through mail-order advertisements and set up house in the rich hills of northern California. San Francisco was one of the most popular places in the country to honeymoon. Couples found it to be a cheerful city with enough sights to occupy their time for months. The presence of many new partners gave the location a sense of solace that helped make the mail-order pairs feel at home as well. San Francisco innkeepers competed for the business of honeymooning couples, offering them a variety of goods and services in return for staying at their establishments. The rivalry between the hotels was fierce and often made front-page news.

So great has become the competition between three or four of the leading city's hotels in the solicitation for bridal couples that the most successful of the landlords in this effort presents each one of the brides who stop at his hostelry a beautiful bouquet or basket of cut flowers. The clerk who receives the couple inquires of the bridegroom if he suspects a recent marriageâand it is seldom that a mistake is madeâand then the flowers go up to the apartments engaged.

One of the most lucrative classes for the landlords is the newly married. Beginning in October and ending in April, it is estimated that there are in the city an average all the time of two hundred pairs of brides and grooms. The manager of the hotel which entertains most of them says he frequently has forty couples, and averages over twenty-five during the busy season. They are, he says, the most desirable class of guests. Always pleasant, they want the best of everything, and are given it. This hostelry makes a feature of pleasing those people, and all embarrassments are lessened to the minimum. Guests there are so used to seeing large numbers of brides and grooms that they are spared the stares so customary where this class is rare.

It is said to be the purpose of the great hotel company organizing here, and which intends to build a structure at a cost of $2,500,000, to arrange one floor with bridal apartments.

Matrimonial News

âJanuary 1887

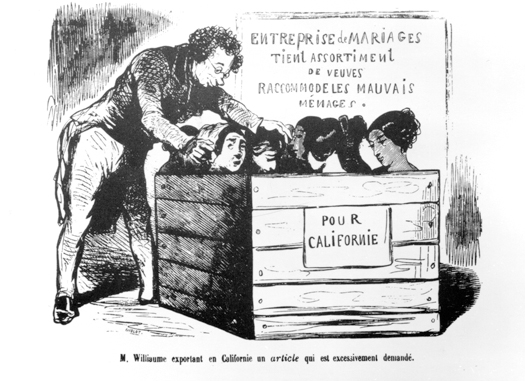

French advertisement, 1857. A marriage broker packages brides set for shipment to California, where women are in high demand.

CALIFORNIA HISTORY ROOM, CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA

KATHLEEN FORRESTSTALL

Irish Bride in Waiting

A

weather-beaten stage labored over a rocky incline, then came to a stop to give the tired team of horses a chance to rest. Three road-weary passengers emerged from the coach and looked around. Eighteen-year-old Kathleen Forreststall was among them. She was a tall woman with red hair, green eyes, and a shocking number of freckles scattered across her face. She stared down at the valley below and at Fort Klamath in the near distance. She had left her home in County Cork, Ireland, on March 10, 1853. Five months later she was now looking out over the Oregon territory that was to be her new home.

Kathleen's journey to the West had been a difficult one. Since reaching the states, she'd encountered rugged terrain, torrential downpours, and hostile Indians, and been robbed of her life savings. Nevertheless, considering the tragic life she had left behind in her homeland, these struggles were much more bearable.

Kathleen was born on November 16, 1835, in Waterford, Ireland. Her parents were farmers who had seven children to help them work a thirty-two acre plot of land that belonged to a British couple. She was the oldest girl and dreamed of becoming a schoolteacher. Kathleen was an exceptional student, and her mother and father encouraged her in all of her scholastic endeavors. When she was fourteen, however, a countrywide famine forced her to reevaluate her life's pursuit.

By the time Kathleen became a teenager, the population in Ireland was more than eight million. There were few industries, so the country depended largely on agriculture. Farms decreased in size as the population grew. Most of the people, such as the Forreststalls, lived as tenants on the small farms they worked, and most of the produce they raised had to be turned over to the landlord as rent. Kathleen's family, and others like them, had to struggle to survive on what was left from their production.

In 1848, a blight or disease infected the crops, rotting potatoes. Millions faced starvation. During the time of the first failed crops, Kathleen lost her mother and five of her siblings to hunger and sickness. Many of Kathleen's neighbors and friends were emigrating out of the country and making their way to America or Canada. Kathleen, having watched her family starve, determined she would leave Ireland as soon as she could raise the money to do so.

An opportunity arose when a doctor who was paying a visit to the Forreststall home shared a copy of a San Francisco paper with Kathleen. The publication contained ads from pioneers and western settlers searching for wives, and many articles told of the shortage of women in the remote areas of the West and the opportunities available for adventurous females seeking a new life. Kathleen poured over the advertisements looking for a suitable solicitor. Within the numerous announcements was a plea from a young soldier: “In the interest of lifelong companionship and devotionâI am submitting this notice. I am a soldier with the United States Army. I am 27 years of age and of good, sturdy stock. I would like to correspond with a lady interested in matrimony.”

Lieutenant Fred M. Careyâ1851

Kathleen sent a letter off to Lieutenant Carey describing her background, religious views, physical appearance, and desire to marry. Their written courtship was short, and the lieutenant proposed to Kathleen in his second letter. He also sent along the funds necessary for her to make her way to America.

After bidding farewell to her father and sisters, she boarded a ship and set sail in search of a better life. The voyage across the Atlantic was challenging.

Kathleen was hundreds of miles from Ireland but still feeling the pangs of hunger, because the vessel was poorly equipped with provisions. She survived on stale crackers and tea until the ship docked at the Isthmus of Panama, where she was able to purchase bananas and bread. She befriended another woman on the journey and the two spent a great deal of time together, swapping secrets and plans for the future. Kathleen foolishly told her new confidant the hiding place for the money sent to her by the lieutenant. Before the ship made port again, the woman had stolen $300 that Kathleen had sewn into the lining of one of her dresses.

When Kathleen arrived in San Francisco, she was virtually penniless. She sent a wire to the groom-to-be, and Lieutenant Carey arranged to pay for her stage fare. After a long, grueling ride, the coach arrived at Fort Klamath. Kathleen's lieutenant was there to meet her.

Fred Carey was a shy, unassuming, slightly balding man who stood barely over five-feet-five-inches tall. The two smiled at one another and politely shook hands. He escorted her to the Fort's guest quarters and after giving her a chance to unpack, the two set out for a walk.

Kathleen and Fred spent two days getting to know each other. He explained the vagabond lifestyle of a soldier and she agreed to take on all the responsibilities that were expected of an Army wife. A wedding date was set for the next time a minister would be at the Fort. A pair of officers' wives offered to help Kathleen make preparations for the big day.

A week before Fred and Kathleen exchanged vows, the lieutenant was ordered to escort a supply wagon to Fort Walla Walla in the northern portion of the state. The couple said their goodbyes and the lieutenant promised to hurry back. As he left, Kathleen realized for the first time how much she had become attached to him. She had not anticipated falling in love but, happily, she had.

During Fred's absence, a social was held in honor of the Fort's commanding officer's birthday. An array of food was served, parlor games were played, and there was music and dancing. Kathleen joined in the festivities, contributing a pie to the banquet and agreeing to dance with some of the soldiers. She had a delightful time and made sure those around her were equally as joyful.

Upon Fred's return, the men in his service complimented him on his choice for a wife. They bragged about her cooking and talent as a dancer. Fred was horrified to learn that his intended had engaged in such “inappropriate” behavior while he was away. He confronted Kathleen, who, seeing no harm in what she had done, confessed to the actions.

The outraged and humiliated lieutenant called off the wedding. Kathleen begged him to reconsider, but he refused. Adding insult to injury, he demanded the money he invested in his mail-order bride be returned.

In order to earn the funds needed to repay Fred, Kathleen took on the job as the Fort's laundry woman. Once financial restitution had been made, she relocated to San Francisco. Historical records show that she answered another advertisement for a mail-order bride, and this time, successfully married the ad's author. The newlyweds moved to a mining camp in Placer County and opened a boarding house.

Lieutenant Fred M. Carey never married.