Hearts West (12 page)

Authors: Chris Enss

THE RED STOCKING SNOOZERS

A

cold Sierra wind blew past the lace-curtained window of a quaint Victorian home overlooking the lush Nevada City, California, terrain. Inside, three elegantly dressed ladies sat fireside, sipping tea and discussing the rough elements who lived and worked in the town's mining camps. It was 1878, and the hills across the Gold Country were filled with unattached, rambunctious prospectors. Once the sun had set and they could no longer work their claims, they made their way to the saloons to drink away their free time. Refined females considered such behavior to be an abomination and the source of great trouble. The proper ladies at the tea party believed the love of a good woman could deter coarse miners from these depraved activities and bring about civility in their community.

Taking a cue from other frontier entrepreneurs, the women decided to make a written appeal to single females in the East to come to the West. With the abundance of available men in the region, the ladies were hopeful numerous matches would be made. Several obstacles needed to be overcome, however, before such a venture could be launched.

Lack of funding to support such a grand endeavor would be a major hurdle, but first there was a local group that needed to be dealt with before any potential brides arrived. Young bachelors in the area had organized a secret society whose principal object was the suppression of the female sex.

Members of the newly organized “Tea Trio” society recognized the necessity of disbanding the bachelor society, and plans were made to bring about its demise. They sought a young reporter with a local newspaper, and, promising the timid man a bride of his own, asked him to join the bachelors' secret club and publish his findings. In case he should meet with an untimely death, the ladies promised to defray the expense of his funeral.

The eager young man set to work and made inquiries of those suspected of being members of the group. After tackling half a dozen, one society bachelor willing to share information with the reporter was found. The gentleman wasn't an inducted part of the organization yet, but he had a friend who was. The friend agreed to submit the reporter's name to the group, and if he was accepted, his initiation would follow that night.

The following article, written by the journalist about his experience, appeared in the Nevada County newspaper, the

Daily Transcript

.

My application was favorably received at the next regular meeting. I had gone to bed. It was 11:30 p.m. when I was informed by the committee of my success, and led to the place of the meeting in the bushes half way up the north side of Sugar Loaf. I was blindfolded and the initiation ceremony was most peculiar. Finally, the bandage (a lady's lace handkerchief) was removed in response to an order like this, “Proclaim the fact of his redemption and let the blind behold!”

The sight that met this reporter's eyes cannot be adequately described. The members sat in a circle on the ground. In the absence of President Mike Garver, Jerry Payne was called to the chair, or rather a boulder, which answered the same purpose. Joe Fleming and George Stewart were hanging on to a monstrous banner to keep it from being blown over by the breeze. On this banner was inscribed the name of the order “THE RED STOCKING SNOOZERS.” Am Lord, Dex Ridley and L. Sukeforth were taking turns throwing wood upon the campfire that illumined the mysterious scene, and at the same time discussing topics of current interest, such as the new style of fall bonnets, etc.

The two Fulweiler Brothers were playing seven-up with the queens left out of the pack. M. Rosenburg and H. Hirshman had been stationed one on the summit and the other at the foot of Sugar Loaf to give warning of approaching danger.

Among other names proposed for membership during the evening were those of Walter Vinton, Fred Searls and Archie Nivens. George Hentz moved that the applications be allowed to remain over for one month. Hentz seconded his own motion. It was put to a vote and carried unanimously. Everything was going along smoothly until Am Lord discovered the President pro-tem wearing a white vest and mauve-colored necktie. This created a suspicion among the members that Jerry's faith was weakening. He saw the storm brewing, and rising, began to speak. In a few well chosen words, he sharply criticized former members who had “for years” shared the benefits of the society, and had basely deserted it, “seeming” he added, “to embrace the first opportunity. A woman!”

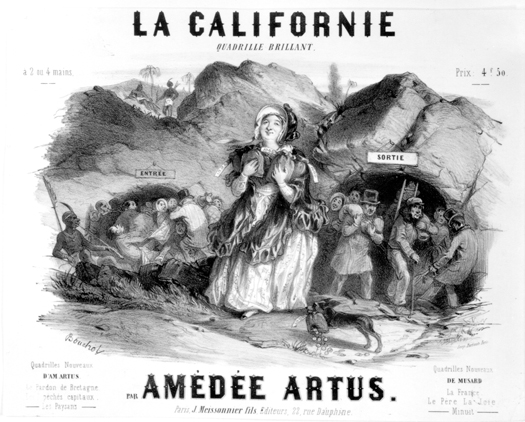

French advertisement, 1857. A French woman stands between two mines where California Argonauts bid for her affections and the chance to be her husband.

CALIFORNIA HISTORY ROOM, CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA

“I call the gentlemen to order,” hastily interrupted John Bacigalupi. “If the President knows anything he knows that according to the Constitution the name of wo____, that is to say fe____, of course you understand, the other sex of our species is not to be spoken of or about on such occasion as this.”

The president glared upon the crowd and singling out Si Jackson who lately joined and was extremely bashful, fastened his eye upon him and said sternly, “Sit down!”

“Go to thunder!” was the prompt response.

Charley Fulweiler smiled approvingly, but detecting the president looking at him with considerable austerity, squirmed so that he put his foot in the hat of Jesse Holcomb, who had dropped in, in a friendly sort of way.

“Now gentlemen, what I want to say is this,” said H. Hirshman, who had left his post at the foot of the hill to join the conclave. “We need a higher discipline in our organization. We need so to speak, a sort of spartan firmness, we need . . .”

“You will need to get your lives insured before we get through with you,” shrieked a female voice a short distance away. “Gim'me the club, Sarah. Oh, gimme it quick!”

There was the sound of rushing skirts through the bushes. The meeting adjourned in confusion, and the members scattered in every direction.

The guards had been negligent in their duties, and when the indignant Tea Trio reached the scene of the “Red Stocking” deliberations, there wasn't a young man to be found.

Harris LongfieldâMarch 3, 1878

There is no historical information available to indicate that the Red Stocking Snoozers continued to get together after their encounter with the Tea Trio. The Trio did continue to meet but shifted their focus from matchmaking to raising funds for orphans.

ELIZA FARNHAM

The Dedicated Sponsor

The mission is a good one, and the projector deserves success. The enterprise in which Mrs. Farnham has engaged is one which evinces much moral courage. Her reward will be found in the blessings, which her countrymen will invoke for her when the vessel in which the association is to sail shall have arrived in California with her precious cargo. May favoring gales attend the good ship Angelique.

Horace Greeley, NewspapermanâApril 12, 1849

E

liza Farnham stepped off the spacious packet ship

Angelique

, docked in the San Francisco harbor, and scanned the bustling, seaside city with a smile. The pier was lined with curious, enthusiastic men waiting to introduce themselves to the more than 200 young ladies who had replied to Eliza's ad seeking marriageable women to accompany her to the West. Taking the hand of each of her young sons, she proceeded proudly down the gangplank. All eyes were fixed on the thin, bespectacled author and lecturer, on her intelligent, deep-set eyes, and her dark hair arranged in prim ringlets around her face. She stopped and waited for her charges to disembark. Just three ladies who dared to take the trip across the ocean followed after Eliza.

The happy expressions the hopeful men wore were at once replaced with disappointed sneers. Lonely miners, who had come to California seeking a fortune in gold in 1849, were eagerly looking forward to seeing members of the opposite sex. Men outnumbered women on the emerging frontier by more than twelve to one. When news of Eliza's trip to the Gold Country reached their desperate ears, they believed she would be bringing 10,000 eligible ladies with her.

Disgruntled pioneers from every profession took to the saloons to drink away their dreams of finding a wife among Eliza's few recruits. The streets were soon filled with intoxicated men using their fists to work out their frustrations. Miner Dashel Greech reported of the scene: “I verily believe there was more drunkenness, more gambling, more fighting, and more of everything that was bad that night, than ever before occurred in San Francisco within any similar space of time.”

It was precisely this volatile, dissolute way of life that Eliza sought to correct. She believed the gentling influence of good women could bring positive lasting changes for western pioneers and miners, and could help tame the Wild West in the process. Many notable historians described her at the time as “a woman bent on doing the world as much good as possible.”

Born on November 17, 1815, in Rensselaerville, New York, Eliza Woodson Burhans was raised by an overbearing aunt and drunkard uncle. Her mother passed away when she was five, and she never knew her father. Her upbringing was strict and troubled, plagued with abuse and neglect. She managed to rise above her struggles, however, finding solace in her schoolwork, as well as in books by Voltaire and Thomas Paine.

In 1835, at the age of twenty, Eliza made her first trip west, traveling over the Santa Cruz mountains in a buggy. The trip was grueling, but exhilarating for the young woman who gained strength in the beauty of the open country. She had read about the spacious landscape of the western frontier and wanted to see the unsettled prairie firsthand. She considered the new territory “a wholly honest place where mankind could push the boundaries of all he believed possible in himself and his world.”

Upon her return from her adventures out West, she moved to Illinois to live with her sister and brother-in-law. It was there, in the Prairie State, that she met a young New England lawyer named Thomas Jefferson Farnham. After a brief courtship the pair married in the fall of 1836. Eliza, who never saw herself as attractive, was transformed by Thomas's love. “I never imagined myself clothed with external splendor, or gifted with beauty, until approving eyes gazed upon me,” she wrote.

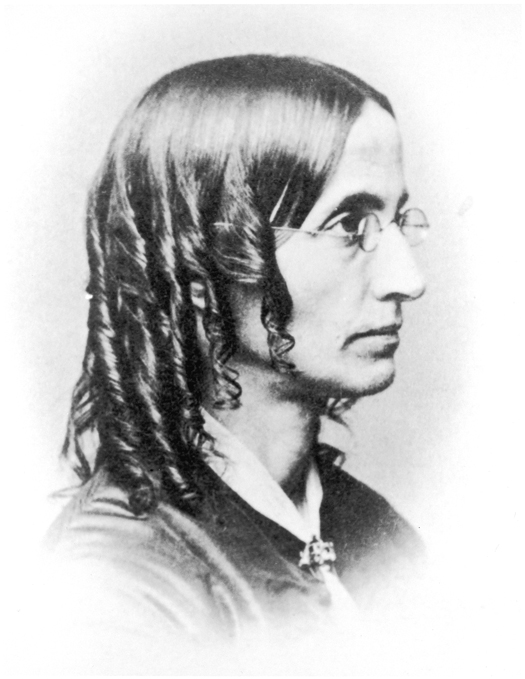

Eliza Farnham

CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FN-05824

Thomas moved his new bride into a quaint two-room cottage, and presented her with a chestnut pony as a wedding gift. For a while they were blissfully happy.

In 1838, she gave birth to their first son. But the following year the couple watched him suffer with yellow fever and die. The disease also took her sister's life. She buried the pair together. “It is a devastating time,” she wrote, “My sister is gone and my boy. His little coffin . . . seemed to carry my very heart into the earth with it.”

Thomas mourned the loss by taking a job as leader of an emigrant party heading to Oregon. Eliza remained behind, pouring her sorrows out on paper. She traveled throughout Illinois by stagecoach, compiling notes for a book she hoped to one day write.

Not long after Thomas returned from his overland trek, he moved his wife east to New York. He wrote extensively about his trip across the frontier, and by 1846 had published four guidebooks. After giving Thomas two more sons, Eliza realized her dream of seeing her own work in print. Her first manuscript, published in 1843, focused on what she called “a woman's moral and spiritual superiority.” Her subsequent work centered on the same theme, pondering the importance of a woman's role as a civilizer in frontier society. Her profound declarations and ideas shocked most readers, generated attention from politicians, and prompted a job offer from the Sing Sing Prison, where she was invited to serve as jail matron for the women's section.

Eliza was twenty-seven when she accepted the position at Sing Sing, and she set about immediately to change the cruel ways in which female inmates were treated. She brought the establishment out of its dark age, where harsh fire-and-brimstone religiosity was practiced, and into a new era where prisoners were supplied with books and taught to read.

Feeling restless and increasingly resentful of Eliza's popularity as a reformer, Thomas went west again in 1847. A year later, while visiting San Francisco, he fell ill and died from complications of pneumonia. Once Eliza heard of Thomas's death, she left at once for California. With her arms around her sons, nine-year-old Charles and eleven-year-old Edward, Eliza walked through the muddy, unpaved San Francisco streets toward the mortuary. Rowdy men filled every thoroughfare, parading from gaudy gambling house to gaudy saloon and back again like ants. Bawdy music spilled out of windows and doors of the bars, and guns fired at all hours of the night. Eliza drank in what she deemed “a wild, depraved sceneâthe reckless abandon of a city raging with Gold Rush fever.”

The lack of women in this rambunctious setting did not escape her attention. She was one of a handful of females in the Gold Country and wherever she went, men stared at her. “Doorways filled instantly,” she wrote, “little islands in the street were thronged with men who seemed to gather in a moment, and who remained immovable until I passed.”

Recalling her belief that women were “civilizers in a frontier society,” a plan began to take shape. “If this rugged area were to be reformedâit would take women to bring that change about,” she later wrote. After a short rest, Eliza began the journey back to the East Coast with the idea to petition single women to move to California as “checks upon the many evils” there.

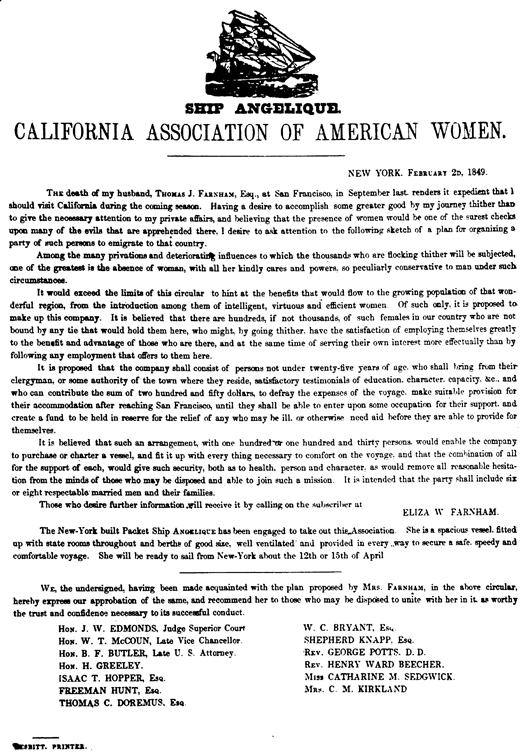

On February 2, 1849, Eliza drafted an advertisement to be published in New York papers that explained her intentions:

It is proposed that the company shall consist of persons not under twenty-five years of age, who shall bring from their clergyman, or some authority of the town where they reside, satisfactory testimonials of education, character, capacity, etc., and who can contribute the sum of two hundred and fifty dollars, to defray the expenses of the voyage, make suitable provision for their accommodation after reaching San Francisco, until they shall be able to enter upon some occupation for their support, and create a fund to be held in reserve for the relief of any who may be ill, or otherwise need aid before they are able to provide for themselves.

To give her advertisement an air of respectability and authority she hoped would further attract prospective brides, she secured endorsements from leading political figures like Horace Greeley, William Cullen Bryant, and Henry Ward Beecher. More than 200 ladies responded to Eliza's broadside, but a sudden illness kept her from being able to actively organize the expedition. In the end, only a handful of brides-to-be agreed to go to California with her.

Reformer Eliza Farnham authored this broadside encouraging single women to come West and act as “cheers upon many of the evils there.”

CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, VB-4

Eliza and her entourage set sail on April 15, 1849. The trip was widely publicized in frontier newspapers. Lonely miners eagerly anticipated the arrival of the packet ship

Angelique

, hoping to find a wife among its gentle freight. Some men, such as miner Henry Holmes, made mention of the forthcoming event in their daily journals. “Went to church three times today,” Holmes reported, “A few ladies present, does my eye good to see a woman once more. Hope Mrs. Farnham will bring 10,000.”

Not everyone found the idea of supplying single pioneers with potential brides acceptable. Many socialites considered it a scandalous plan, and the campaign was mired in controversy. Rumors that Eliza was little more than a procurer ultimately kept many women from committing to the journey.

The highly anticipated trip to San Francisco was troublesome from the start. Eliza challenged the authority of the ship's captain, demanding he make an unscheduled stop for fresh water. Furious with what he referred to as a “brazen female meddler,” the captain lured Eliza and her charges off the ship in Chile and left them stranded there. A long, anxious month passed before they were able to catch another ship for San Francisco. Eliza and her boys arrived at their new home in Santa Cruz in February of 1850, and from there proceeded to find the land that had been left to them. After a short carriage ride through the country, the three arrived at the homestead. The house itself was little more than a shack, but the acreage around it was lush and filled with cattle. “An ideal place to raise a family,” she would later write in her book,

California, In-Doors and Out

.