Hell-Bent (11 page)

Authors: Benjamin Lorr

Rest reveals this is not just muscular exhaustion. Use of my left shoulder has simply disappeared.

The next two days are spent in wonderment and fear at this new development. It turns out that most of my range of motion is intact. Swinging side to side, pulling weight down, scratching my right ear, and zipping my fly all feel normal. But one particular motion—it almost feels like a channel my arm cannot pass through—is impossible. As if the muscles needed there have gone blank. Lifting my arm with the elbow directly beneath the forearm—the motion of shampoo applications and water bottle to lips—is simply unavailable to me. My arm begins the movement, gets to a certain point, and then quivers. Like it has been frozen midair by a magician.

It is a highly specific and completely painless paralysis.

Taking class with this absence is baffling. Despite the limited physical mobility, every action is even more exhausting than before. Instead of a rest for the muscles, the lack of movement drains me. And the harder I focus, the more exhausting it becomes. It is frustration I am unable to put into words

until I find a description by

neuroscientist Richard Restak of a recovering stroke victim:

Each small gain in ability to move the limb brought with it a sense of heaviness and resistance, as if the arm were being held down by heavy weights. The harder he tried to move, the greater fatigue and the greater effort required. This inner sense of exerting a mental force against a feeling of inner resistance was later described … “as a kind of mental force, a power of will. … As if there was a resistance which could be overcome … some kind of mental energy.”

Esak notices it in class the next day before I can tell him. I am sure this has less to do with his exceptional perception, more to do with the fact that my postures look deranged. When we talk afterwards, he is firm. First, I must stop doing wall-walks if I want my arm to return. I nod and silently note that he poses this as a question. Second, he tells me this is totally and completely normal. It means I am doing things right. He tells me it happened to him early in his training and his shoulder came back completely within a month. I nod again, silent at the prospect of a month without my shoulder.

Over the next few days, I become obsessed with regaining the range of motion, staring at myself helpless in the mirror as I make stunted gestures. I also become obsessed with whether other Backbenders believe me. The work we are doing is so hard and so exhausting that my shoulder seems like a convenient excuse. Like a psychological manifestation designed to save my body from this torture. But instead of wariness, the other Backbenders embrace my condition. David is especially warm. The same thing happened to him in a previous Backbending to both shoulders simultaneously. He tells me I’m holding up well and that he was terrified. And for the first time I start to belong.

What is amazing is that at no time do I ever get really get angry. Not

with Esak, not with myself. I have this extremely worrisome, strokelike phenomenon that has debilitated my ability to function and that has a very clear and indisputable cause (i.e., doing wall-walks correctly). And instead of anger or doubt, I feel pretty calm about the whole situation. I have this weird sensation that my body is simply adjusting. That this is just part of the process. The only time I actually get scared is when I conduct a thought experiment: If this doesn’t make me quit—what type of injury would?

When we line up to take Beginners Class—the basic series of twenty-six postures that makes up the Bikram regime—I end up next to Esak so much that it’s a joke among the people in my car. I know why too, I’m always rushing in late, and nobody else wants to step into the spot. Everyone wants to take it easy during class, save their energy for the nightly routines. But nobody wants to let Esak down. That, of course, makes me perfect for my role. Compared to everyone else here, I already know I’m going to let him down.

During class, I notice Esak squirm a lot. I notice him grimace and pop out of postures a few seconds early. At first I think my presence annoys him. That he wants to bend next to someone who can inspire him. Then I think that he is lowering himself to my presence: the master teacher incrementally altering his instruction for each student. And while I’m not ruling out either possibility, I think there is another reason. The basic series of Bikram Yoga is just really, really hard. Even if you are the best in the world. That is what it is. Hardness as definition. Meaning, if it’s not hard, you’re not doing it right.

One of the few days I’m not lined up directly next to Esak, he is teaching the Beginners class. It’s a 10 A.M. on a weekend. Members of the general public—non-Backbenders—are taking class with us, and the room is packed.

The density of bodies and Esak’s intensity make the class feel hotter than normal. A big linebacker-sized fellow toward the back of the room is gasping. I can hear him huffing. Then stomping. Then there is silence as he goes down in a crumple. Esak keeps teaching the class without even a pause of acknowledgment. Eventually the linebacker gets up and stumbles toward the door to leave class for the locker room.

Esak stops him before he can make it. Instead he has the man kneel right by the lip of the firmly shut door. So close to relief. “You are free to leave right now,” he tells the man, whose blocklike head is in his hands, and who is audibly wheezing again. “But you have a choice. Sometimes your yoga is in the postures. Today, your yoga is recognizing you have a choice.”

Then after instructing us to come out of a posture, with a voice aimed directly at my heart, “Everyone else—stop listening! Stop thinking! Don’t imagine his class is easier than yours. Don’t flatter yourself with your effort. Right now, this is the person working hardest in this class. He is getting every benefit he can.

“What you need to ask yourself,” Esak continues, “is whether you are getting the same benefits he is. Just because you’re still standing doesn’t mean you’re still doing the yoga like he is. If you aren’t putting the same effort into it, you’re doing nothing. No benefits. You might as well walk out of the room, because if you limp through this series, you’re flattering yourself if you think you’re doing yoga.”

It’s a funny thing that way. Someone standing and looking very impressive in the mirror and someone sitting hunched over doing almost nothing. Same yoga.

Much later, I would meet a yoga teacher—Alison Tavares from Arizona—who would make this dynamic even clearer. We are sitting poolside in San Diego; it is seventy degrees with a slight breeze, impossibly far from the stink and oppression of the yoga room. Alison tells me about teaching a class with three men she loved. One, the first student she ever taught, was a triathlete in his late twenties, the type that might shave his chest to cut down his swim time. To his left was her father, in his late seventies, a few months in recovery from cardiac bypass surgery. His chest had been shaved at the spot where his doctors had sawed through his breastbone and implanted a defibrillator. And last in the row was

her husband, an ex-marine, now

paraplegic, out of his wheelchair on the floor balanced on the remainder of his legs. All three in the same posture. All three side by side. Watching them, she realized this radical, almost Vitruvian quality of the yoga. It was metric, adapting to the individual. Each of the men in front of her was a dedicated student; each spoke enthusiastically to her about the benefits they

received from the yoga. But to an outsider, each appeared at an impossibly different place, and in the case of her paraplegic husband, potentially not even doing the same posture. What they shared was a commonality of exertion, and a commonality of form to which they poured this effort.

After class, I find the man in the locker room. He’s sitting on the floor with his back against a corner. His face is red, and it’s unclear if he’s been crying. Everyone else is walking around him.

So it’s the greatest relief to have Esak next to me, struggling. Legs trembling, occasionally coming out of a posture early to sneak a break. It’s a relief because for the first time, I don’t feel like such a clod. Because in the beginner series we’re all leveled, all equal. But it’s also a relief, because I know he’s legit. Only a fraud could make it through flawlessly every time.

And then it’s over.

On the last day of Backbending, Esak teaches class. There is a small moment in the beginning of every class where students are given a tiny break. The official Bikram dialogue calls it a warm-up, a moment where you walk your hips “several times, right and left and right and left.” At Backbending, Esak has forbidden us to take the warm-up. The idea being that we are training to be champions, and champions don’t need warm-ups—they go right into postures. In the last class, when we get to that part, he says for whatever reason, “Go ahead, walk your legs out. … Ah yes, a little treat.” Despite being in class, I laugh out loud at the joke, and then, almost like I’m choking on the sensation, I suddenly start crying. It’s inexplicable and actually the first time I have ever cried in the yoga room. These aren’t tears of sadness exactly, more self-recognition: It is such a small, simple movement and it feels so good on my aching body.

Hours later, even after we have packed our things away, David’s house retains a battered feel. The hardwood floors are visible again, but there are still small overlooked remnants hiding in plain sight. Reminders: a stray lime on a shelf, a forgotten pair of yoga shorts on a doorknob, a couch that may forever stink like Bengay. Everyone is circling around, giving hugs, promising to keep in touch, making rash commitments to come to the next Backbending, wherever it will be.

As thanks, a group of students presents Esak and David with custom-made T-shirts that read JEDI FIGHT CLUB—CHANGE YOUR MIND. Esak gets positively bouncy with enthusiasm. He sits on David’s staircase, wearing the shirt, hugging people good-bye, accepting donations as they leave.

When it is my turn, I slip Esak as large a check as I can reasonably write and quietly tell him I wish I could triple it. The sentiment is real. I hug him good-bye with my gimpy shoulder, then quickly leave for the car. My body is wires at this point. I walk in stutters. I have learned a lot in the last two weeks, perhaps more about my body than in the preceding two years, but as soon as I pull out of the driveway, I decide to stop all backbends until I see a doctor.

The next day, driving back to New York, I find myself doing wall-walks against the aluminum siding of a rest-stop gas station. There is a moment, just prior to unbuckling the seat belt, where I wonder what I’m doing. But by the time I’m actually at the wall, I just shrug my shoulders, roll my eyes at the sky, and arch back to meet the pain like it’s a moral obligation. When I’m done, my shirt is off and I’m smiling like a fool. Guess it turns out I’m a junkie too.

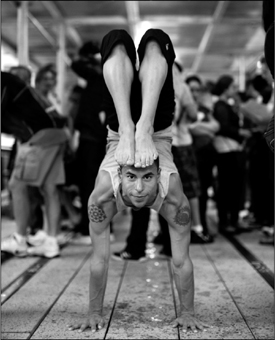

Joseph Encinia in handstand scorpion pose

Heartbreak opens

for even breaking is opening … My spirit takes journey, my spirit takes flight, and I am not running. I am choosing. I am broken. I am broken open. Breaking is freeing. Broken is freedom. I am not broken; I am free.

—

DEE REES THROUGH THE CHARACTER OF ALIKE

Emmy

Emmy is Bikram’s oldest student, and theirs is a special relationship. Emmy is the only person left who can criticize Bikram in public. She is the only one who can scorn him. Who can reference the fact that his physical skills are in decay. That his ego has turned him into a cartoon. She can joke at him and not just with him. They love each other; they insult each other; they fight with each other. But above all, they need each other. Bikram is remarkable. And Emmy is remarkable in ways that complement Bikram without encroaching.

At eighty-three, she is almost regal in bearing: spine solid as a crowbar when she walks, white hair perpetually pinned up, single pearls on her ears. In her long, tight dresses, at the many formal events that dot the Bikram landscape, she introduces you to the concept of octogenarian sexy.

When Emmy teaches, she never rises to the podium, never sits on Bikram’s throne. Instead she circulates the room, talking softly into her headset microphone as her voice broadcasts out through the mounted speakers on the wall. The effect, especially in the megarooms of hundreds, is ghostly.

Unlike Bikram, who is a focal point when he teaches, demanding even more attention than the mirrors, Emmy is everywhere and nowhere. She wanders up and down the aisles of bending practitioners, giving highly specific modifications, and it is impossible to know whether she is far or near until suddenly you feel a firm, bony finger pushing at your pelvis, and the voice from the speakers is telling the room to “push the hip forward. Really, now. It is just impossible to balance if you don’t push it forward.”

Where Bikram believed American students would never be ready for anything more than basic postures, Emmy wrestled the Advanced Series out him. She still teaches the class weekly at the International Headquarters. Occasionally she will demonstrate. Her postures are beautiful, her instructions clipped. “Stop fidgeting! There is no fidgeting in yoga. You look like a cat clawing around before it takes a shit.” There is no class quite like Emmy’s in the Bikram universe; she has mastered all the guru’s knowledge and yet made it entirely her own.