Hitler's Last Secretary (26 page)

Read Hitler's Last Secretary Online

Authors: Traudl Junge

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Military, #World War II

Wedding to Hans Junge, 19 June 1943

The newly-weds: Traudl and Hans Junge with the witnesses to their wedding, Otto Günsche (left) and Erich Kempka (right)

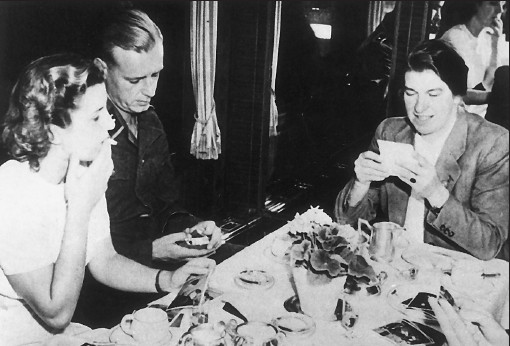

In the Führer’s special train: Traudl and Hans Junge with Johanna Wolf (right) looking at their wedding photographs (photo: Walter Frentz)

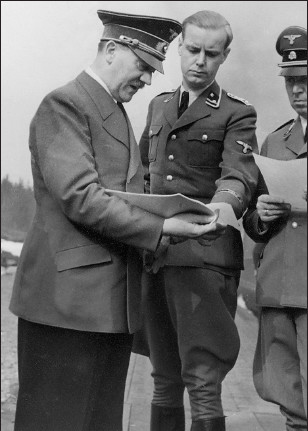

Adolf Hitler with his orderly Hans Junge, early 1940s

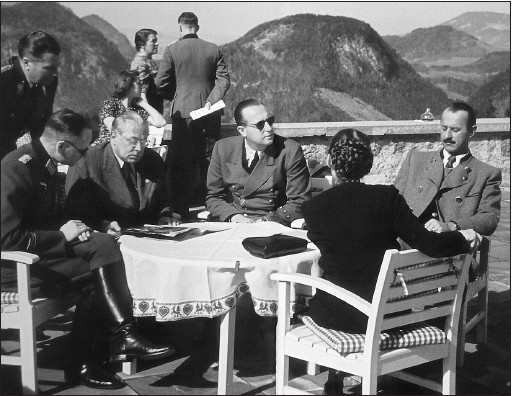

On the Berghof terrace, 1943, seated left to right: Lieutenant Colonel Gerhard Engel, Heinrich Hoffmann (with Traudl Junge behind him), Walther Hewel, Gerda Bormann (back view), State Secretary for Tourism Hermann Esser (photo: Walter Frentz)

In conversation with Sepp Dietrich, 1943 (photo: Walter Frentz)

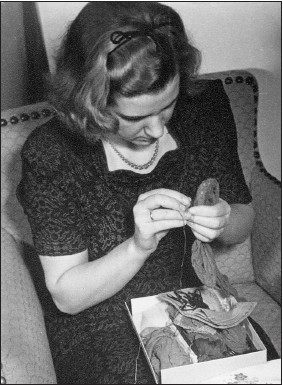

The evening ritual: darning stockings in her room at the Wolf’s Lair Führer headquarters, 1943

Only Adolf Hitler’s meals were cooked in the diet kitchen at the Wolf’s Lair. From left to right: Marlene von Exner, kitchen assistant Wilhelm Kleyer, Traudl Junge, late 1943

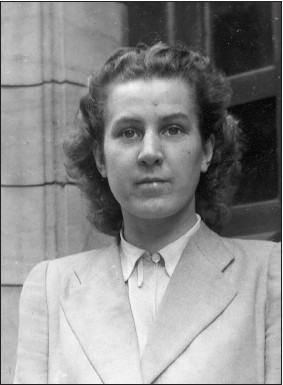

Photograph for her new identity card, Berlin, November 1945

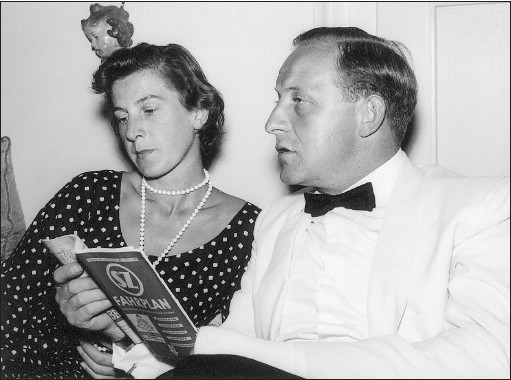

Traudl Junge with her fiancé, Heinz Bald, 1955

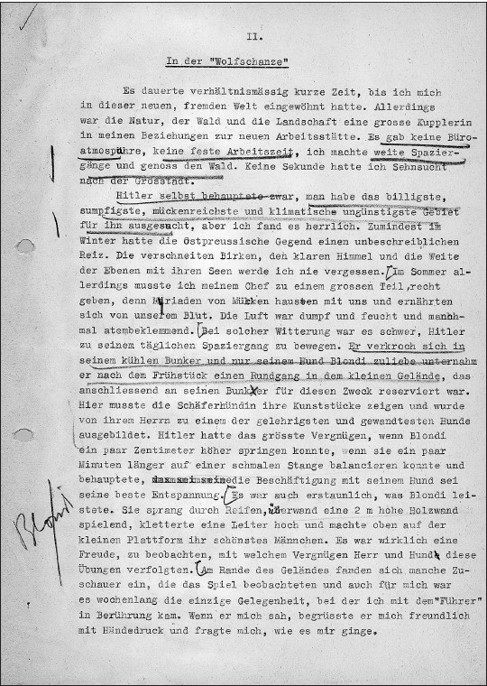

Traudl Junge’s original typescript of 1947

When we came back there was another air-raid warning. The raids were coming thick and fast now, concentrating on the area round the Reich Chancellery. We had almost got used to the artillery fire. We noticed only when the roaring noise stopped. Once again we were sitting with Hitler. He was getting more oddly behaved and difficult to understand all the time. Just as yesterday he hadn’t said a word to suggest that he didn’t think victory certain, today he said with equal conviction that there was no longer any hope for a change in the situation. We pointed to the picture of Frederick the Great looking down from the wall, and now we all quoted the words Hitler had used so often. ‘My Führer, where’s the last battalion? Don’t you believe in the lessons of history any more?’ He shook his head wearily. ‘The army has betrayed me, the generals are no good for anything. My orders haven’t been carried out. It’s finally over. National Socialism is dead and will never rise again!’ How upset we were to hear these words! The change had been too sudden. Perhaps we hadn’t really and truly meant it when we said we wanted to stay in Berlin? Perhaps we had hoped to get away with our lives after all. Now Hitler himself was depriving us of that hope.

Eva Braun developed a kind of loyalty complex. ‘You know,’ she told Hitler, ‘I can’t understand the way they’ve all left you. Where’s Himmler, where are Speer, Ribbentrop, Göring? Why didn’t they stay with you where they belong? And why isn’t Brandt here?’ And Hitler, who may well have been thinking how readily and light-heartedly many whom he had raised to great heights had now abandoned him, spoke up for his men. ‘You don’t understand, child. They can serve me better if they’re out of here. Himmler has his divisions to lead, Speer has important work to do, they all have their official duties which are more important than my life.’ ‘Yes,’ said Eva Braun, ‘I can understand that. But take Speer, for example. I mean, he was your friend. I know him, I’m sure he will come.’

During this conversation Himmler rang. Hitler left the room and went to the telephone. He came back looking pale, his face rigid. The Reichsführer had been trying once again, by phone, to get Hitler to leave the city. Once again the Führer had firmly refused. He spoke quite impersonally of his intended suicide, as if it were something to be taken for granted. And we kept seeing our own deaths before our eyes as well as his. We were getting used to the idea. But I hardly slept that night.

Next day the artillery fire comes closer again. The Russians have moved into the suburbs of the city. There is desperate fighting against a huge number of mighty tanks. The situation in the bunker is still the same. We sit and wait. Hitler has become dull and listless after his outburst of fury yesterday, when he shouted about betrayal. It’s as if he has abdicated his office. There are no official military briefings now, the day has no set timetable. In the bright light reflected from the white concrete walls we don’t notice day giving way to night. We secretaries keep close to Hitler, always uneasily expecting him to put an end to his life. But for the time being he goes on with this half-life. Goebbels has brought his state secretary Dr Naumann

96

and his adjutant Schwägermann

97

with him. They are discussing a final propaganda campaign with Hitler. The population must know that the Führer is in the besieged city and has undertaken its defence. That, they say, will give people strength to resist and make the impossible possible. But while the desperate and homeless flee from the ruined buildings and seek refuge in the U-Bahn tunnels, while every man and every boy is supposed to fight and risk his life using some kind of makeshift weapon, Hitler has already buried all hope.