Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (22 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

4.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

He had at last begun to attract more followers, most of them women, educated, middle-class, married. It is hard to understand at this distance how he gained any converts to the idea that we’re all living inside the concavity of a hollow earth. Indeed, it is hard to understand why the hollow earth business was such an important part of Teed’s creed in the first place. Possibly the women just thought it an incidental quirk, forgiving this further evidence of male weirdness, focusing instead on his belief in a male/female God, his insistence on equality of the sexes, and a peaceful life of chastity outside the dungeon of marriage. By this time he had also added another appealing promise—his followers would enjoy personal immortality. Possibly, too, it was a certain sexy charisma on Teed’s part. He wasn’t big, about 5’6” and 165 pounds, but he had square-jawed good looks, a deep resonant voice, and an unwavering focus to his eyes usually described as “forceful” and “penetrating.”

By 1888 the number of believers had so grown that he signed a lease on “a large double brick house on the corner of 33rd Place and College [Cottage] Grove Avenue,” where he set up his largest celibate community to date.

43

The numbers continued to increase in a modest way, and four years later the core group moved into expanded quarters. By then Teed counted 126 followers in Chicago, nearly three-quarters of them women, almost all living in or near a South Side Washington Heights enclave of eight and a half acres containing a mansion, cottages, beautiful gardens and shady walks, and two ponds big enough for ice skating in the winter. They called the compound Beth-Ophra. An 1894 article in the

Chicago Herald

described it as “a fine property … surrounded by broad, shady verandas and magnificent grounds thickly studded with old trees and made attractive by grass plats and flower beds. With … [Teed] in the same fine building live some of the prominent angels [of his church]. There are seven cottages besides in which other members of the Koreshan community live, and an office building—formerly a huge barn—in which is the printing office.”

44

Today this once peaceful spot lies beneath the Dan Ryan Expressway, thundered over nonstop by trucks pounding along, except during rush hour gridlock.

43

The numbers continued to increase in a modest way, and four years later the core group moved into expanded quarters. By then Teed counted 126 followers in Chicago, nearly three-quarters of them women, almost all living in or near a South Side Washington Heights enclave of eight and a half acres containing a mansion, cottages, beautiful gardens and shady walks, and two ponds big enough for ice skating in the winter. They called the compound Beth-Ophra. An 1894 article in the

Chicago Herald

described it as “a fine property … surrounded by broad, shady verandas and magnificent grounds thickly studded with old trees and made attractive by grass plats and flower beds. With … [Teed] in the same fine building live some of the prominent angels [of his church]. There are seven cottages besides in which other members of the Koreshan community live, and an office building—formerly a huge barn—in which is the printing office.”

44

Today this once peaceful spot lies beneath the Dan Ryan Expressway, thundered over nonstop by trucks pounding along, except during rush hour gridlock.

Eventually Teed began looking around for an unspoiled pastoral place to build a new community from scratch, where his New Jerusalem might arise. And how would he recognize the right place? It would be at “the point where the vitellus of the alchemico-organic cosmos specifically determines,” another of those recondite locutions Teed was so fond of. He also called this special spot “the vitellus of the cosmogenic egg.” By cosmogenic egg he meant the earth, and the more common word for vitellus is yolk—though here he was probably using it in the sense of “embryo.” The yolk is inside the egg, of course, its center. In other words, in Koreshan cosmology, they were seeking to locate their magnificent city at the center of the center,

inside

the earth.

inside

the earth.

Teed set off from Chicago in 1893 with an entourage of three women—Mrs. Annie G. Ordway, Mrs. Berthaldine Boomer, and Mrs. Mary C. Mills. They followed an itinerary set by prayer. Robert Lynn Rainard says that “each night the group sought in devotions guidance for the following day’s journey. Spiritual direction ‘guided’ them into Florida and to their ultimate destination.”

45

In January 1894, they found themselves in Punta Rassa on the southwest coast, a few miles west of Fort Myers at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. Today the peninsula is occupied by the Sanibel Harbour Resort and Spa near the causeway to toney Sanibel Island. Punta Rassa was a former cattle shipping town that had died after the Civil War, reborn in the 1880s as a sportfishing resort for the wealthy, complete with its own fancy hotel, the Tarpon House Inn. Teed and his attractive spiritual helpmeets were stopping there when they had a momentous encounter. Rainard says:

45

In January 1894, they found themselves in Punta Rassa on the southwest coast, a few miles west of Fort Myers at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. Today the peninsula is occupied by the Sanibel Harbour Resort and Spa near the causeway to toney Sanibel Island. Punta Rassa was a former cattle shipping town that had died after the Civil War, reborn in the 1880s as a sportfishing resort for the wealthy, complete with its own fancy hotel, the Tarpon House Inn. Teed and his attractive spiritual helpmeets were stopping there when they had a momentous encounter. Rainard says:

At Punta Rassa the Koreshans met an elderly German named Gustav Damkohler, and his son Elwin, who were on their way back from their Christmas visit to Fort Myers. Teed engaged Damkohler in conversation which led to the Koreshans being invited to visit Damkohler’s homestead at the Estero River, twenty miles down the coast from Punta Rassa. Damkohler, who had been a Florida pioneer since the early 1880s, had lost his wife in child-birth, and all but one child to the treacheries of pioneer life. A man in need of companionship, Damkohler was receptive to the fellowship of the Koreshans and the pampering of their women. At Estero Dr. Teed came to the realization that he had been directed to the remote Florida wilderness by the Divine Being.

The Koreshan Story

, a more “official” account, though not necessarily a more accurate one, has this fortuitous meeting taking place differently. According to it, a prospective seller had sent Teed train tickets to inspect a property on Pine Island, Florida, just north of Punta Rassa, and in December 1893 he and the three women went to check it out. It proved prohibitively expensive, but while in Punta Gorda, Teed had taken the opportunity to give a few lectures and distribute a few pounds of Koreshan pamphlets, and some of this literature found its way to Damkohler, who wrote a letter to Teed—in German, sent in a Watch Tower Society envelope covered with biblical quotes.

The Koreshan Story

has it, “as Victoria Gratia (Annie Ordway) held the letter (unopened) she seemed to know that it would lead them back to Florida that winter to the right place to begin.” Back in Florida in January 1894, the momentous meeting took place in Punta Rassa. Teed lit right into expounding his doctrines, and Damkohler soaked it all in like a sponge: “Tears of joy rolled down the man’s cheek, and he exclaimed repeatedly, ‘Master! Master! The Lord is in it!’ He then besought them to come with him and see the land he had held for the Master.”

, a more “official” account, though not necessarily a more accurate one, has this fortuitous meeting taking place differently. According to it, a prospective seller had sent Teed train tickets to inspect a property on Pine Island, Florida, just north of Punta Rassa, and in December 1893 he and the three women went to check it out. It proved prohibitively expensive, but while in Punta Gorda, Teed had taken the opportunity to give a few lectures and distribute a few pounds of Koreshan pamphlets, and some of this literature found its way to Damkohler, who wrote a letter to Teed—in German, sent in a Watch Tower Society envelope covered with biblical quotes.

The Koreshan Story

has it, “as Victoria Gratia (Annie Ordway) held the letter (unopened) she seemed to know that it would lead them back to Florida that winter to the right place to begin.” Back in Florida in January 1894, the momentous meeting took place in Punta Rassa. Teed lit right into expounding his doctrines, and Damkohler soaked it all in like a sponge: “Tears of joy rolled down the man’s cheek, and he exclaimed repeatedly, ‘Master! Master! The Lord is in it!’ He then besought them to come with him and see the land he had held for the Master.”

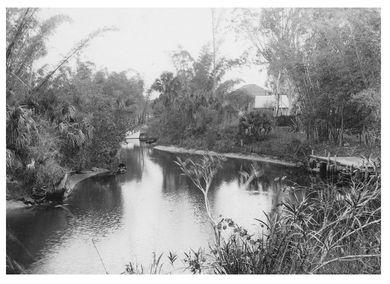

This early view of the Estero River facing east reveals the wild tranquility of the setting Teed selected for his New Jerusalem. The roof in the middle distance belongs to Damkohler’s original cottage. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

Except for their mutual religious fervor, Damkohler and Teed were a study in contrasts. Teed, sleek, meticulously groomed, given to custom-tailored suits, cultured, sophisticated, silver-tongued. And Damkohler, an aging swamp rat, though a handsome one, with forceful features, silvery hair, and an abundant white beard, lacking sight in one eye, more at home speaking German than his halting English.

Damkohler wanted them to see his land right away. They set out down the coast in a borrowed sailboat. At Mound Key they stopped for supper around a fire. Navigating through coastal mangrove thickets, they used two rowboats to make their way up the small sinuous Estero River, captivated by the wild serene beauty of the place, its solemn stillness, sand pines and cabbage palms rising more than forty feet above the placid coffee-colored river, alligators snoozing on the banks, the occasional bright chirp and chatter of tropical birds. They reached Damkohler’s little landing around ten o’clock at night on New Year’s Day 1894. The circumstances were rather more spartan than Teed was accustomed to. The only building was Damkohler’s one-room board cabin, where all camped out. As

The Koreshan Story

describes their arrangements,

The Koreshan Story

describes their arrangements,

The cabin also had a front and back porch, but furnishings were scant. They sat on boxes to eat their meals from a broad shelf built into the back porch. The chief bed was in the cabin’s living room and was assigned to the three sisters. The ladies lay cross-wise with the tall Victoria’s feet resting on boxes along side the bed. Dr. Teed, Mr. Damkohler and the boy slept on cots and piles of old sails on the floor of the attic. This old cabin still stands in Estero today…. Dr. Teed busied himself grubbing and clearing land, while the women were occupied with improving the cabin, preparing meals and other activities about the place. For food and supplies they were obliged to row and sail to Pine Island. The river provided fish and Damkohler’s beehives produced excellent honey.

It sounds like a pleasant idyll. Teed remained three weeks before returning to Chicago, possibly because Damkohler needed additional convincing when it came to turning over the land. Damkohler seems to have been ready to give the Koreshans half his 320 acres, but Teed was urging him to deed over the other half as well—for a token price of one dollar. Thrifty German Damkohler wasn’t so sure about that, but in the end he gave in. The deal they finally struck was $200 for three hundred acres, with Damkohler holding on to twenty for himself. He would later have second thoughts.

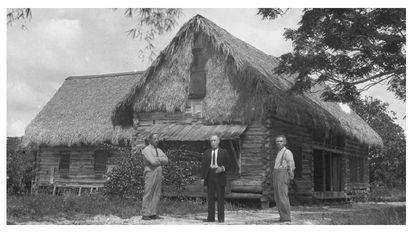

The women stayed on—their company no doubt added inducement to Damkohler—while Teed took the train back to Chicago to put together a group of recruits. A few weeks later twenty-four Koreshans arrived from Chicago and began constructing a two-story L-shaped log building with a thatched roof (known as the Brothers House) as a temporary shelter while they built the first of the community’s permanent buildings. They also put up white canvas “tent-houses” beneath groves of live oaks, with overhangs to create shady front porches with raised wooden floors and decorated with cheery trailers of flowering plants; they were big enough for a few wicker rockers and canvas deck chairs—quite inviting looking in the surviving photographs.

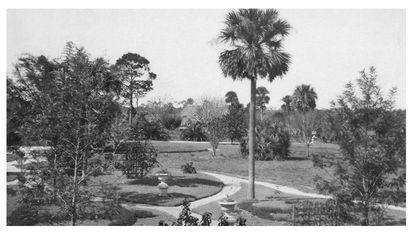

Over the next years they gradually turned Damkohler’s wilderness (he had cleared only one of his 320 acres) into a charming tidy community consisting of over thirty buildings, extensive gardens, and pleasing walkways laid out in a radial pattern from the community’s center. Estero never became the mighty megalopolis of Teed’s dreams. It was to be, he wrote, “like a thousand world’s fair cities. Estero will manifest one great panorama of architectural beauty … Here is to exist the climax, the crowning glory, of civilization’s greatest cosmopolitan center and capital … which shall loudly call to all the world for millions of progressive minds and hearts to leave the turmoil of the great time of trouble, and make their homes in the Guiding Star City.” Estero would be the primary city on earth—or rather

in

it—with a population of 10 million. His plan called for a star-shaped radial geometry reminiscent of Pierre L’Enfant’s graceful design for Washington, DC, boasting grand avenues four hundred feet across, “with parks of fruit and nut trees extending the entire length of these streets,” as an 1895 Koreshan publication describes it. It continues:

in

it—with a population of 10 million. His plan called for a star-shaped radial geometry reminiscent of Pierre L’Enfant’s graceful design for Washington, DC, boasting grand avenues four hundred feet across, “with parks of fruit and nut trees extending the entire length of these streets,” as an 1895 Koreshan publication describes it. It continues:

The construction of the city will be of such a character as to provide for a combination of street elevation, placing various kinds of traffic upon different surfaces; as for instance, heavy team traffic upon the ground surface, light driving upon a plane distinct from either, and all railroad travel upon distinct planes, dividing even the freight and passenger traffic by separate elevations. There will be no dumping of sewage into the streams, bay or Gulf. A moveable and continuous earth closet will carry the ‘debris’ and offal of the city to a place thirty or more miles distant, where it will be transformed to fertilization and restored to the land surface to be absorbed by vegetable growth. There will be no smudge or smoke. Power by which machinery will be moved will be by the utilization of the electromagnetic currents of the earth and air, independently of steam application to so called ‘dyanmos.’ Motors will take the place of motion derived from steam pressure. The city will be constructed on the most magnificent scale, without the use of so called money. These things can be done easily once the people know the force of co-operation and united life, and understand the great principles of utilization and economy.

46Brothers House, one of the first structures the Koreshans built on the tangled Florida wilderness they bought from Gustav Damkohler. (Koreshan State Historic Site)Koreshan manicured grounds, with walkways meandering through beautiful plantings and the occasional stone urn overflowing with flowers in bloom—truly a garden in the wilderness. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

Other books

Everything I Shouldn't / Everything I Need by Stacey Mosteller

Until There Was You by J.J. Bamber

In the Clear by Tamara Morgan

The Splendor Of Silence by Indu Sundaresan

A Wild and Lonely Place by Marcia Muller

The Hollow by Nora Roberts

A Last Goodbye by J.A. Jance

Retribution: An Alpha Billionaire Romance (Secrets & Lies Book 3) by Lauren Landish

Low Red Moon by Kiernan, Caitlin R.

Shadow Flight (1990) by Weber, Joe