Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (11 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

5.2Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

For an ideal people, they’re a little short, averaging five feet tall. But they’re tremendously athletic, able to leap thirty feet at a single bound—probably because of their natural, healthy diet, being strict vegetarians and teetotalers. True to the universal racism of the time, their utopian skin is whiter than white—fair-colored Seaborn resembles the “sootiest African” by comparison. Of course they’re all handsome and beautiful. And they generally live to be two hundred years old. The Symzonian form of government is pure democracy, and the society is an uncorrupted meritocracy.

Seaborn’s reaction to all this seems worth quoting at length, as it represents Symmes’ critique of America at the time:

This state of things appeared to me at first to be beyond the limits of possibility in the external world…. My mind was for some time occupied by reflecting upon the extraordinary difference in the

natural

condition of the internals and externals…. I perceived that the greater part of the labour of the externals was devoted to the production of things useless or pernicious; and that of the things produced or acquired, the distribution, through defects in our social organization, was so unequal, that some few destroyed, without any increase of happiness to themselves, the products of the toil of multitudes… . Instead of devoting our time to useful purposes, and living temperately on the wholesome gifts of Providence, like the blest internals, so as to preserve our health and strengthen our minds, thousands of us are employed in producing inebriating liquors, by the destruction of wholesome articles of food, to poison the bodies, enervate the minds, and corrupt the hearts of our fellow beings. Other thousands waste their strength to procure stimulating weeds and narcotic substances from the extreme parts of the earth, for the purpose of exciting diseased appetites…. Still greater numbers give their industry and their lives to the acquistion of mere matters of ornament, for the gratification of pride, an insatiable passion, which is only stimulated to increase its demands with every new indulgence…. I saw that the internals owed their happiness to their rationality, to a conformity with the laws of nature and religion; and that the externals were miserable, from the indulgence of inordinate passions, and subjection to vicious propensities.

But even Symzonia isn’t entirely perfect. They do have their occasional criminals and degenerates. What do they do with them? Exile them to a far land near the northern polar opening, where they grow darker from the sun and become larger due to their gross habits. You guessed it. In ancient times, groups of them wandered over the rim onto the External world, and all of us are the descendents of these debased outcast misfits—thus all the rotten behavior prevailing out here on our side.

Soon the Symzonians conclude that they have to get rid of these Externals, lest their edenic society be infected by them. How do they decide this might happen? By reading our world’s great literature! Seaborn has brought along all sorts of books—including the complete Shakespeare and Milton’s

Paradise Lost.

The Symzonians have translated them into their own language, studied them carefully, and decided that the Externals are hopelessly corrupt. So Seaborn & Co. are peacefully 86’d and sent on their way. Rather than head home empty-handed, while still in the southern polar regions, they slaughter 100,000 seals for their skins, sail to Canton, exchange them there for “China trade” goods, which they bring home, sell, and become rich—briefly. Seaborn’s broker cheats him and goes under, and he’s broke, so he writes the book in hopes of recouping his losses via a best seller. It didn’t work.

Paradise Lost.

The Symzonians have translated them into their own language, studied them carefully, and decided that the Externals are hopelessly corrupt. So Seaborn & Co. are peacefully 86’d and sent on their way. Rather than head home empty-handed, while still in the southern polar regions, they slaughter 100,000 seals for their skins, sail to Canton, exchange them there for “China trade” goods, which they bring home, sell, and become rich—briefly. Seaborn’s broker cheats him and goes under, and he’s broke, so he writes the book in hopes of recouping his losses via a best seller. It didn’t work.

Few copies of

Symzonia

were sold, but still he kept at it. Little had changed since that first circular in 1818, which he delivered “to every learned institution and to every considerable town and village, as well as to numerous distinguished individuals, throughout the United States, and sent copies to several of the learned societies of Europe,” according to the 1882

History and Biographical Cyclopedia of Butler County Ohio.

20

“It was overwhelmed with ridicule as the production of a distempered imagination,” the entry continues, “or the result of partial insanity. It was for many years a fruitful source of jest with the newspapers. The scientific papers of Europe generally treated it as a hoax, rather than believe that any sane man could issue such a circular or uphold such a theory.” Even so, Symmes continued to produce circulars and publish newspaper articles, and he wrote

Symzonia

as well. These seem only to have compounded the ridicule, but he wouldn’t quit.

Symzonia

were sold, but still he kept at it. Little had changed since that first circular in 1818, which he delivered “to every learned institution and to every considerable town and village, as well as to numerous distinguished individuals, throughout the United States, and sent copies to several of the learned societies of Europe,” according to the 1882

History and Biographical Cyclopedia of Butler County Ohio.

20

“It was overwhelmed with ridicule as the production of a distempered imagination,” the entry continues, “or the result of partial insanity. It was for many years a fruitful source of jest with the newspapers. The scientific papers of Europe generally treated it as a hoax, rather than believe that any sane man could issue such a circular or uphold such a theory.” Even so, Symmes continued to produce circulars and publish newspaper articles, and he wrote

Symzonia

as well. These seem only to have compounded the ridicule, but he wouldn’t quit.

Writing about it didn’t put his theory over, so in 1820, Symmes began lecturing. Probably no would-be public lecturer was ever worse equipped to do so. A contemporary said of him, “His voice is somewhat nasal, and he speaks hesitatingly, and with apparent labor.”

21

A 1909 article by John Weld Peck in the

Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

says, “As a lecturer he was far from a success. The arrangement of his subject was illogical, confused, and dry, and his delivery was poor.” Peck adds, “However, his earnestness and the interesting novelty of his subject secured him attentive audiences wherever he spoke.” Train wrecks always draw crowds. Even his friend James McBride, in the biographical sketch appended to his book on Symmes’ theory, admits his deficiencies.

21

A 1909 article by John Weld Peck in the

Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

says, “As a lecturer he was far from a success. The arrangement of his subject was illogical, confused, and dry, and his delivery was poor.” Peck adds, “However, his earnestness and the interesting novelty of his subject secured him attentive audiences wherever he spoke.” Train wrecks always draw crowds. Even his friend James McBride, in the biographical sketch appended to his book on Symmes’ theory, admits his deficiencies.

Captain Symmes’s want of a classical education, and philosophic attainments, perhaps, unfits him for the office of a lecturer. But, his arguments being presented in confused array, and clothed in homely phraseology, can furnish no objection to the soundness of his doctrines. The imperfection of his style, and the inelegance of his manner, may be deplored; but, certainly, constitute no proof of the inadequacy of his reasoning, or the absurdity of his deductions.

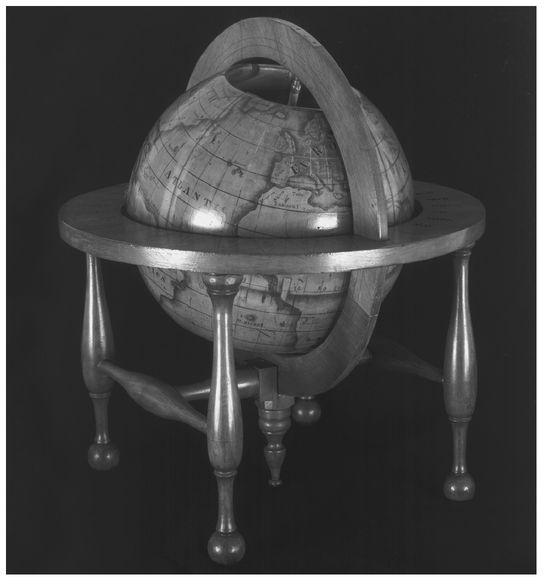

Symmes began this unfortunate enterprise with lectures in Cincinnati and Hamilton, Ohio—his eventual home and burial place. Then for the next several years he took the show on the road, lecturing wherever they’d have him, dragging along a globe customized to demonstrate his polar openings. These appearances seem painful even to contemplate.

In 1822 Symmes petitioned Congress to equip an expedition, with him as leader, to either of the poles to locate the opening there, urging both the great profit and glory that would derive from it. Somehow he persuaded Kentucky senator Richard M. Johnson to present it. After a few remarks the petition was permanently tabled. He tried again in December 1823, asking for an expedition to test the “new theory of the earth,” adding that, theory or not, “there appear to be many extraordinary circumstances, or phenomena, pervading the Arctic and Antarctic regions, which strongly indicate something beyond the Polar circles worthy of our attention and research.” This met with similar result. In January 1824 he petitioned the Ohio General Assembly to pass a motion approving his theory and to “recommend him to Congress for an outfit suitable to the enterprise,” according to the

Butler County

history. “On motion, the further consideration thereof was indefinitely postponed.” Then in 1825, hearing of an arctic expedition the Russians were about to mount, he applied through the American minister to go along; approval was granted, but with no money attached, and he couldn’t afford to do so—yet another disappointment in a life full of them.

Butler County

history. “On motion, the further consideration thereof was indefinitely postponed.” Then in 1825, hearing of an arctic expedition the Russians were about to mount, he applied through the American minister to go along; approval was granted, but with no money attached, and he couldn’t afford to do so—yet another disappointment in a life full of them.

John Cleves Symmes’ globe. (The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia)

He did make one notable convert in his lifetime—Jeremiah Reynolds. Nearly twenty years younger than Symmes, Reynolds had grown up in southwestern Ohio, attended Ohio University without quite getting a degree, and was editing the

Wilmington Spectator,

a paper he had started in that small Ohio city, when he met Symmes in 1824. He was so taken with his theory of concentric spheres that he quit his job to join Symmes on tour as a co-lecturer. Given his subsequent career, one has to wonder about his sincerity in this, whether he might not have simply been looking for the main chance, a way out of a small-potatoes job in a small-potatoes town. He’s an intriguing figure, a major footnote in American literature due to his later influence on both Poe and Melville.

Wilmington Spectator,

a paper he had started in that small Ohio city, when he met Symmes in 1824. He was so taken with his theory of concentric spheres that he quit his job to join Symmes on tour as a co-lecturer. Given his subsequent career, one has to wonder about his sincerity in this, whether he might not have simply been looking for the main chance, a way out of a small-potatoes job in a small-potatoes town. He’s an intriguing figure, a major footnote in American literature due to his later influence on both Poe and Melville.

Reynolds, a natural promoter and entrepreneur, seems to have persuaded the reluctant, stay-at-home Symmes that they needed to take the show on the road, to embark on a national lecture tour to promote his theory. They set out lecturing together in September 1825, starting with a few dates in Pennsylvania.

22

Where Symmes was halting, often seeming confused, his new partner generally wowed skeptical audiences who had come to scoff. In Chambersburg, the editor of the local newspaper wrote that he’d considered Symmes’ ideas “wild effusions of a disordered imagination.” But on hearing Reynolds, he and the rest of the audience were “completely enchained” because Reynolds presented “facts, the existence of which will not admit of a doubt, and the conclusions drawn from them are so natural, so consistent with reason, and apparently in such strict accordance with the known laws of nature, that they almost irresistibly enforce conviction on the mind.” In Harrisburg Reynolds spoke before the legislature, and, according to William Stanton, “fifty of the lawmakers responded with an enthusiastic letter that urged the government to equip an expedition, for the promise it held out was ‘quite as reasonable as that of the great Columbus’ and ‘better supported by facts.’”

22

Where Symmes was halting, often seeming confused, his new partner generally wowed skeptical audiences who had come to scoff. In Chambersburg, the editor of the local newspaper wrote that he’d considered Symmes’ ideas “wild effusions of a disordered imagination.” But on hearing Reynolds, he and the rest of the audience were “completely enchained” because Reynolds presented “facts, the existence of which will not admit of a doubt, and the conclusions drawn from them are so natural, so consistent with reason, and apparently in such strict accordance with the known laws of nature, that they almost irresistibly enforce conviction on the mind.” In Harrisburg Reynolds spoke before the legislature, and, according to William Stanton, “fifty of the lawmakers responded with an enthusiastic letter that urged the government to equip an expedition, for the promise it held out was ‘quite as reasonable as that of the great Columbus’ and ‘better supported by facts.’”

In Philadelphia, they had a major falling-out. Symmes’ health was tricky, and Reynolds offered to take on the entire burden of lecturing—

his

way. Reynolds realized the tactical rewards in downplaying the wackier parts of the theory while stumping for a national polar expedition on its own merits, which he wanted to lead. But Symmes refused to compromise about how the theory should be presented, and the brief partnership ended. Symmes packed up his globe and went off lecturing on his own in the northeast and Quebec, giving several talks at Union College in Schenectady and even spoke to a group of students at Harvard University before ill health forced him to stop. Too sick to make it back home, he went instead to his birthplace in New Jersey, where he was the guest of an old friend of his father until he at last recuperated enough for the journey to Ohio. “When he reached Cincinnati in February, 1829,” McBride’s

Pioneer Biography

says, “he was so feeble that he had to be conveyed on a bed placed in a spring wagon, to his home near Hamilton”—the farm his namesake uncle, Judge Symmes, had given him a few years earlier. He died on May 29, 1829. He was forty-eight years old.

his

way. Reynolds realized the tactical rewards in downplaying the wackier parts of the theory while stumping for a national polar expedition on its own merits, which he wanted to lead. But Symmes refused to compromise about how the theory should be presented, and the brief partnership ended. Symmes packed up his globe and went off lecturing on his own in the northeast and Quebec, giving several talks at Union College in Schenectady and even spoke to a group of students at Harvard University before ill health forced him to stop. Too sick to make it back home, he went instead to his birthplace in New Jersey, where he was the guest of an old friend of his father until he at last recuperated enough for the journey to Ohio. “When he reached Cincinnati in February, 1829,” McBride’s

Pioneer Biography

says, “he was so feeble that he had to be conveyed on a bed placed in a spring wagon, to his home near Hamilton”—the farm his namesake uncle, Judge Symmes, had given him a few years earlier. He died on May 29, 1829. He was forty-eight years old.

Of his many children, Americus, born at the Bellefontaine fort north of St. Louis in 1811, tried to keep his father’s light burning. Americus arranged to have a monument built on his gravesite in Hamilton, Ohio, an obelisk surmounted by a stone hollow globe twenty inches across and open at the poles, and in 1878 wrote his explanatory apologia,

The Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres, demonstrating that THE EARTH IS HOLLOW, HABITABLE WITHIN, AND WIDELY OPEN AT THE POLES,

a book that elucidated the theory with updated “evidence” from polar exploration that had occurred since his father’s death. At seventy-one, he was still giving interviews in support of his father’s theories, telling a

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

writer, “If my father’s plan was adopted, the riddle of an open polar sea could soon be solved, the pole reached, and Symmes’s new world found.” Loyal to the end.

The Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres, demonstrating that THE EARTH IS HOLLOW, HABITABLE WITHIN, AND WIDELY OPEN AT THE POLES,

a book that elucidated the theory with updated “evidence” from polar exploration that had occurred since his father’s death. At seventy-one, he was still giving interviews in support of his father’s theories, telling a

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

writer, “If my father’s plan was adopted, the riddle of an open polar sea could soon be solved, the pole reached, and Symmes’s new world found.” Loyal to the end.

An article by B. St. J. Fry, in the August 1871

Ladies Repository

says in summary:

Ladies Repository

says in summary:

Captain Symmes deserves a tender remembrance, and his friends never failed to cherish his memory, and regret that his last years were so full of cheerless mortification. Had the opportunity been afforded him to penetrate the polar latitudes, his faith and courage would have made him one of the boldest adventurers, and he would scarcely have failed to return with useful information and the broader and more truthful views that are now held by intelligent men. No man of his day had studied the subject more thoroughly, and his plans for penetrating the icy North were those that later explorers have adopted with advantage. But his theory has so many of the elements that are woven into childish Munchausen stories, that few men could consider it with any degree of seriousness. But the men who so readily discarded them were for a time deceived by Locke’s famous “moon hoax,” which had as little common sense to recommend it, and which was less susceptible of proof. For many of Captain Symmes’s surmises have been proven to be well founded, but they do not in any wise establish his theory.

Other books

Saint Peter’s Wolf by Michael Cadnum

Striker (The Alien Wars Book 2) by Paul Moxham

When I Forget You by Noel, Courtney

Doc: A Memoir by Dwight Gooden, Ellis Henican

The Summoning by Kelley Armstrong

Our Daily Bread by Lauren B. Davis

The Haunted Sultan (Skeleton Key) by Gillian Zane, Skeleton Key

As Time Goes By: A BWWM Interracial Romance by Tiffany McDowell

Princess In Love by Meg Cabot

The Girls by Lisa Jewell