Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (27 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

Similarly, few people put their faith in supernatural powers. For those who believe in demons, demons aren’t supernatural. They are an integral part of nature, just like porcupines, scorpions and germs. Modern physicians blame disease on invisible germs, and voodoo priests blame disease on invisible demons. There’s nothing supernatural about it: you make some demon angry, so the demon enters your body and causes you pain. What could be more natural than that? Only those who don’t believe in demons think of them as standing apart from the natural order of things.

Equating religion with faith in supernatural powers implies that you can understand all known natural phenomena without religion,

which is just an optional supplement. Having understood perfectly well the whole of nature, you can now choose whether to add some ‘super-natural’ religious dogma or not. However, most religions argue that you simply cannot understand the world without them. You will never comprehend the true reason for disease, drought or earthquakes if you do not take their dogma into account.

Defining religion as ‘belief in gods’ is also problematic. We tend to say that a devout Christian is religious because she believes in God, whereas a fervent communist isn’t religious, because communism has no gods. However, religion is created by humans rather than by gods, and it is defined by its social function rather than by the existence of deities. Religion is

anything

that confers superhuman legitimacy on human social structures. It legitimises human norms and values by arguing that they reflect superhuman laws.

Religion asserts that we humans are subject to a system of moral laws that we did not invent and that we cannot change. A devout Jew would say that this is the system of moral laws created by God and revealed in the Bible. A Hindu would say that Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva created the laws, which were revealed to us humans in the Vedas. Other religions, from Buddhism and Daoism to Nazism, communism and liberalism, argue that the superhuman laws are natural laws, and not the creation of this or that god. Of course, each believes in a different set of natural laws discovered and revealed by different seers and prophets, from Buddha and Laozi to Hitler and Lenin.

A Jewish boy comes to his father and asks, ‘Dad, why shouldn’t we eat pork?’ The father strokes his long white beard thoughtfully and answers, ‘Well, Yankele, that’s how the world works. You are still young and you don’t understand, but if we eat pork, God will punish us and we will come to a bad end. It isn’t my idea. It’s not even the rabbi’s idea. If the rabbi had created the world, maybe he would have created a world in which pork was perfectly kosher. But the rabbi didn’t create the world – God did it. And God said, I don’t know why, that we shouldn’t eat pork. So we shouldn’t. Capeesh?’

In 1943 a German boy comes to his father, a senior SS officer, and asks, ‘Dad, why are we killing the Jews?’ The father puts on his shiny leather boots, and meanwhile explains, ‘Well, Fritz, that’s how the world works. You are still young and you don’t understand, but if we allow the Jews to live, they will cause the degeneration and extinction of humankind. It’s not my idea, and it’s not even the Führer’s idea. If Hitler had created the world, maybe he would have created a world in which the laws of natural selection did not apply, and Jews and Aryans could all live together in perfect harmony. But Hitler didn’t create the world. He just managed to decipher the laws of nature, and then instructed us how to live in line with them. If we disobey these laws, we will come to a bad end. Is that clear?!’

In 2016 a British boy comes to his father, a liberal MP, and asks, ‘Dad, why should we care about the human rights of Muslims in the Middle East?’ The father puts down his cup of tea, thinks for a moment, and says, ‘Well, Duncan, that’s how the world works. You are still young and you don’t understand, but all humans, even Muslims in the Middle East, have the same nature and therefore enjoy the same natural rights. This isn’t my idea, nor a decision of Parliament. If Parliament had created the world, universal human rights might well have been buried in some subcommittee along with all that quantum physics stuff. But Parliament didn’t create the world, it just tries to make sense of it, and we must respect the natural rights even of Muslims in the Middle East, or very soon our own rights will also be violated, and we will come to a bad end. Now off you go.’

Liberals, communists and followers of other modern creeds dislike describing their own system as a ‘religion’, because they identify religion with superstitions and supernatural powers. If you tell communists or liberals that they are religious, they think you accuse them of blindly believing in groundless pipe dreams. In fact, it means only that they believe in some system of moral laws that wasn’t invented by humans, but which humans must nevertheless obey. As far as we know, all human societies believe in this. Every society tells its members that they must obey some superhuman moral law, and that breaking this law will result in catastrophe.

Religions differ of course in the details of their stories, their concrete commandments, and the rewards and punishments they promise. Thus in medieval Europe the Catholic Church argued that God doesn’t like rich people. Jesus said that it is harder for a rich man to pass through the gates of heaven than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, and the Church encouraged the rich to give lots of alms, threatening that misers will burn in hell. Modern communism also dislikes rich people, but it threatens them with class conflict here and now, rather than with burning sulphur after death.

The communist laws of history are similar to the commandments of the Christian God, inasmuch as they are superhuman forces that humans cannot change at will. People can decide tomorrow morning to cancel the offside rule in football, because we invented that law, and we are free to change it. However, at least according to Marx, we cannot change the laws of history. No matter what the capitalists do, as long as they continue to accumulate private property they are bound to create class conflict and they are destined to be defeated by the rising proletariat.

If you happen to be a communist yourself you might argue that communism and Christianity are nevertheless very different, because communism is right, whereas Christianity is wrong. Class conflict really is inherent in the capitalist system, whereas rich people don’t suffer eternal tortures in hell after they die. Yet even if that’s the case, it doesn’t mean communism is not a religion. Rather, it means that communism is the one true religion. Followers of every religion are convinced that theirs alone is true. Perhaps the followers of one religion are right.

If You Meet the Buddha

The assertion that religion is a tool for preserving social order and for organising large-scale cooperation may vex many people for whom it represents first and foremost a spiritual path. However, just as the gap between religion and science is smaller than we

commonly think, so the gap between religion and spirituality is much bigger. Religion is a deal, whereas spirituality is a journey.

Religion gives a complete description of the world, and offers us a well-defined contract with predetermined goals. ‘God exists. He told us to behave in certain ways. If you obey God, you’ll be admitted to heaven. If you disobey Him, you’ll burn in hell.’ The very clarity of this deal allows society to define common norms and values that regulate human behaviour.

Spiritual journeys are nothing like that. They usually take people in mysterious ways towards unknown destinations. The quest usually begins with some big question, such as who am I? What is the meaning of life? What is good? Whereas many people just accept the ready-made answers provided by the powers that be, spiritual seekers are not so easily satisfied. They are determined to follow the big question wherever it leads, and not just to places you know well or wish to visit. Thus for most people, academic studies are a deal rather than a spiritual journey, because they take us to a predetermined goal approved by our elders, governments and banks. ‘I’ll study for three years, pass the exams, get my BA certificate and secure a well-paid job.’ Academic studies might be transformed into a spiritual journey if the big questions you encounter on the way deflect you towards unexpected destinations, of which you could hardly even conceive at first. For example, a student might begin to study economics in order to secure a job in Wall Street. However, if what she learns somehow causes her to end up in a Hindu ashram or helping HIV patients in Zimbabwe, then we might call that a spiritual journey.

Why label such a voyage ‘spiritual’? This is a legacy from ancient dualist religions that believed in the existence of two gods, one good and one evil. According to dualism, the good god created pure and everlasting souls that lived in a wonderful world of spirit. However, the bad god – sometimes named Satan – created another world, made of matter. Satan didn’t know how to make his creation last, hence in the world of matter everything rots and disintegrates. In order to breathe life into his defective creation, Satan tempted

souls from the pure world of spirit, and locked them up inside material bodies. That’s what humans are – a good spiritual soul trapped inside an evil material body. Since the soul’s prison – the body – decays and eventually dies, Satan ceaselessly tempts the soul with bodily delights, and above all with food, sex and power. When the body disintegrates and the soul has a chance to escape back to the spiritual world, its craving for bodily pleasures draws it back inside some new material body. The soul thus transmigrates from body to body, wasting its days in pursuit of food, sex and power.

Dualism instructs people to break these material shackles and undertake a journey back to the spiritual world, which is totally unfamiliar to us, but is our true home. During this quest we must reject all material temptations and deals. Due to this dualist legacy, every journey on which we doubt the conventions and deals of the mundane world and walk towards an unknown destination is called ‘a spiritual journey’.

Such journeys are fundamentally different from religions, because religions seek to cement the worldly order whereas spirituality seeks to escape it. Often enough, the most important demand from spiritual wanderers is to challenge the beliefs and conventions of dominant religions. In Zen Buddhism it is said that ‘If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.’ Which means that if while walking on the spiritual path you encounter the rigid ideas and fixed laws of institutionalised Buddhism, you must free yourself from them too.

For religions, spirituality is a dangerous threat. Religions typically strive to rein in the spiritual quests of their followers, and many religious systems were challenged not by laypeople preoccupied with food, sex and power, but rather by spiritual truth-seekers who wanted more than platitudes. Thus the Protestant revolt against the authority of the Catholic Church was ignited not by hedonistic atheists but rather by a devout and ascetic monk, Martin Luther. Luther wanted answers to the existential questions of life, and refused to settle for the rites, rituals and deals offered by the Church.

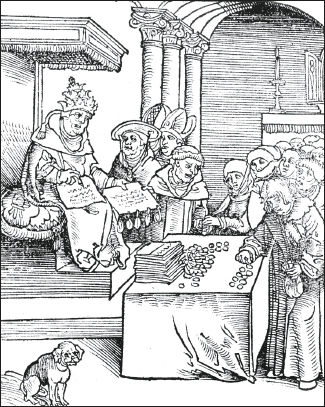

In Luther’s day, the Church promised its followers very enticing deals. If you sinned, and feared eternal damnation in the afterlife, all you needed to do was buy an indulgence. In the early sixteenth century the Church employed professional ‘salvation peddlers’ who wandered the towns and villages of Europe and sold indulgences for fixed prices. You want an entry visa to heaven? Pay ten gold coins. You want Grandpa Heinz and Grandma Gertrud to join you there? No problem, but it will cost you thirty coins. The most famous of these peddlers, the Dominican friar Johannes Tetzel, allegedly said that the moment the coin clinks in the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory to heaven.

1

The more Luther thought about it, the more he doubted this deal, and the Church that offered it. You cannot just buy your way to salvation. The Pope couldn’t possibly have the authority to

forgive people their sins, and open the gates of heaven. According to Protestant tradition, on 31 October 1517 Luther walked to the All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, carrying a lengthy document, a hammer and some nails. The document listed ninety-five theses against contemporary religious practices, including against the selling of indulgences. Luther nailed it to the church door, sparking the Protestant Reformation, which called upon any human who cared about salvation to rebel against the Pope’s authority and search for alternative routes to heaven.

The Pope selling indulgences for money (from a Protestant pamphlet).

Woodcut from ‘Passional Christi und Antichristi’ by Philipp Melanchthon, published in 1521, Cranach, Lucas (1472–1553) (studio of) © Private Collection/Bridgeman Images.

From a historical perspective, the spiritual journey is always tragic, for it is a lonely path fit for individuals rather than for entire societies. Human cooperation requires firm answers rather than just questions, and those who foam against stultified religious structures end up forging new structures in their place. It happened to the dualists, whose spiritual journeys became religious establishments. It happened to Martin Luther, who after challenging the laws, institutions and rituals of the Catholic Church found himself writing new law books, founding new institutions and inventing new ceremonies. It happened even to Buddha and Jesus. In their uncompromising quest for the truth they subverted the laws, rituals and structures of traditional Hinduism and Judaism. But eventually more laws, more rituals and more structures were created in their name than in the name of any other person in history.