Honor Thy Father (36 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

Joseph Bonanno Tucson, Arizona

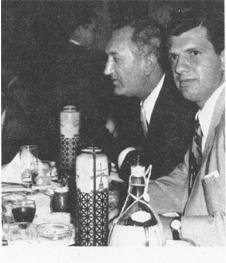

Joseph and son Bill at Moulin Rouge Restaurant, Hollywood, California

Bill Bonanno prepares for federal case

Joseph Bonanno and daughter, Catherine, on her wedding day, Tucson, Arizona, 1960

A

FEW DAYS LATER

, R

OSALIF’S MOTHER FLEW TO

S

AN

F

RAN

cisco from New York carrying among her luggage a box of live snails that she had personally selected at a Brooklyn fish market, live lobsters from Maine, special Italian sausages stuffed with cheese, and other delicacies that were rare in California and that she intended to serve at a large family gathering on the following day, the first Sunday in March.

The dinner, to be attended by a dozen people, would be held at the home of her daughter Ann, who was in her seventh month of pregnancy, and with whom Mrs. Profaci would be staying in San Jose until after the birth; she would help with the cooking, would look after Ann’s two young children, and would also be available for whatever assistance she might provide her eldest daughter, Rosalie, and her youngest daughter, Josephine, who was twenty-one and would be getting married in June, shortly after her graduation from Berkeley.

Josephine would be married in the chapel on the Stanford campus to a non-Catholic, non-Italian, hazel-eyed young man with long blond hair named Tim Stanton, the son of an upper-middle-class family in Westchester County, New York. Josephine had met Tim Stanton at a college barbecue exchange in the spring of 1966 when she was a student at Santa Clara, and during that summer in New York she went with him to the suburbs to meet his parents, an encounter she had dreaded in advance even though, early in their dating, she made it clear to him who her relatives were, learning to her surprise and relief that this precaution was unnecessary; he already knew. The meeting with his parents turned out to be unexpectedly pleasant, because the Stantons succeeded in making her feel welcome and comfortable.

During the next two years, after Josephine had transferred to Berkeley and as her relationship with Tim Stanton became closer and there were plans for marriage, it was not Tim’s family, but Josephine’s, that seemed the more concerned. That it was to be a non-Catholic wedding ceremony was most disappointing to Josephine’s mother and older brother; but when they sensed how determined Josephine was and how inseparable the young couple obviously were, they accepted the inevitable and Josephine’s brother agreed to escort her up the aisle on her wedding day.

The extended family, however, which included Bill Bonanno and his friends in addition to other in-laws and relatives of the Profacis’, still expressed doubts about the wisdom of such a marriage; and by the time of the large family dinner, Tim Stanton had been the subject of several conversations and debates in Brooklyn and San Jose. They had all met him by now, inasmuch as Josephine had introduced him at various times during the last year; and since he was so different from anyone who had ever approached the family threshold before, he was a subject of both fascination and confusion.

Some of Bill’s friends, reacting to Stanton’s long hair and his casual style of dress, and having heard him denounce the war in Vietnam and hint at his own refusal to fight if drafted, regarded him quickly if incorrectly as part of a radical new generation that wished to overthrow the system; and in any showdown with the new generation, Bill’s men would be curiously on the side of the system—the government, the police, and “law and order.” These men did not want the system to collapse, for if it collapsed they would topple with it. While they recognized the government as flawed, hypocritical, and undemocratic, with most politicians and the police corrupt to a degree, corruption was at least something that could be understood and dealt with. What they were most wary of and what centuries of Sicilian history had taught them to mistrust were reformers and crusaders.

Bill Bonanno’s view of the younger generation, however, was less rigid, and he agreed with Tim Stanton on many issues—except when he learned that Stanton was thinking of registering as a conscientious objector or of joining the Peace Corps and serving in Malaysia with Josephine after the marriage. Bill believed that joining the Peace Corps was “copping out” since it was subsidized by the same government leaders who were fomenting war in Vietnam. If Stanton did not wish to engage in an immoral war, then, according to Bill, he should be willing to pay the price and should go to jail. Jail was the place for many honorable men these days, Bill believed, including himself in such company.

Rosalie was not upset by any of Stanton’s political views, but she was distressed that Josephine was marrying outside the church; she preferred that her youngest sister agree to “go along” with the Catholic wedding and the religious beliefs that she had grown up with and ostensibly had accepted until recently. But in this instance, Bill supported Josephine’s decision not to give the appearance of believing what she did not; and yet Bill was bothered by Josephine for other reasons, vaguely definable ones that were inspired by his suspicion that Josephine privately detested him. He was perceptive enough to sense that Josephine remembered well certain raging scenes between himself and the Profaci family after Rosalie had left him in Arizona in 1963 and had returned to New York. Josephine had since then seemed quiet in his presence, occasionally suggesting her disapproval by certain gestures and remarks; and Rosalie herself recently said that Josephine had probably decided on a different course with regard to marriage and religion because Josephine had seen how Rosalie had suffered by following the ways of the past. Bill knew of course that he could count on Rosalie not to miss an opportunity to portray herself as some sort of martyr; but he also knew and took pride in the fact that Rosalie’s sister Ann had never held a grudge against him—Bill and Ann always got along splendidly, and he had often said in jest at family gatherings that he had married the wrong Profaci.

Ann, though a bit heavy like her mother, had a beautiful face, expressive eyes, and, uncharacteristic for a Profaci, a sense of humor. Ann was an efficient homemaker, a wonderful mother, and, while she was intelligent, she deferred to her husband’s judgment; her husband was clearly in charge. But Josephine, Bill was sure, would lead a different life, she was the product of another time. She was the first daughter to finish college, and, without being a feminist, she undoubtedly identified with the cause of modern women seeking greater liberation, which was probably one reason, Bill thought, why she disliked him, for he typified everything that she as a modern young woman undoubtedly rejected—he was the dominant Sicilian male who did as he pleased, came and went as he wished, unquestioned, the inheritor of the rights of a one-sided patriarchal system that the Bonannos and Profacis had lived under for generations.

But at this point, in March 1969, with his mother-in-law visiting San Jose, Bill Bonanno was not eager for any further friction with the Profacis; and at the Sunday dinner that Mrs. Profaci was preparing, and at which Josephine would be present and perhaps also Tim, Bill decided that he would be on his best behavior.

In the morning, however, Bill woke up with a mild headache, and as he went out to the patio with the Sunday newspapers and a book under his arm he noticed that two of Charles’s rabbits had broken out of their pens, had dug into the flower garden, and were now chasing one another wildly around the backyard. The yard was also littered with toys and pieces of wood.

“Rosalie!” Bill yelled to his wife in the kitchen. “Is Chuckie getting out of bed today?”

“He’s not feeling well, and I thought I’d let him sleep for a while.”

“I want him to clean up this mess out here and catch these rabbits!”

“He’s not feeling too well,” she repeated, her voice rising. “What do you want me to do?”

“I told him three times this week I wanted this place fixed up,” Bill said, sitting down on a patio chair in the midmorning sun and putting on his dark glasses. He had stayed up half the night reading the book that he held in his hands, a new novel about the Mafia called

The Godfather

. He was half-finished, and so far he liked it very much, and he thought that the author, Mario Puzo, had insight into the secret society. Bill found the central figure in the novel, Don Vito Corleone, a believable character, and he wondered if that name had been partly inspired by “Don Vito” Genovese and by the town of Corleone, which was in the interior of western Sicily southeast of Castellammare. Bill believed that his own father possessed many of the quietly sophisticated qualities that the writer had attributed to Don Vito Corleone, and yet there were also elements in the character that reminded Bill of the late Thomas Lucchese. Lucchese in real life, like Don Vito Corleone in the novel, had influential friends in Democratic political circles in New York during the 1950s, men who reportedly performed special favors for generous political contributions; and in 1960, Lucchese went to Los Angeles to mingle with some of these friends who were attending the Democratic National Convention. Lucchese favored the nomination of John F. Kennedy, but other dons such as Joseph Profaci, influenced partly by an immigrant Sicilian’s traditional suspicion of the Irish, were against Kennedy. Most Irish politicians, like Irish priests and cops, would do no favors for the Italians, whom, in Profaci’s view, they privately abhorred—a view that Lucchese did not share, nor did Frank Costello, who had been on intimate terms with William O’Dwyer. But after Kennedy became president and after the Irish Mafia rose to power, and when only Valachi among Italians achieved fame in Washington, many mafiosi asserted that Profaci had been right.

The Sicilians described in

The Godfather—

not only Don Vito Corleone and his college-educated son Michael (with whom Bill identified) but other characters as well—were endowed with impressive amounts of courage and honor, traits that Bill was convinced were fast deteriorating in the brotherhood. The novel was set in the years following World War II, and in those days the Mafia was probably as the novelist described it; and as Bill continued to read the book, he became nostalgic for a period that he had never personally known. He read on the patio for nearly an hour, then was interrupted by the sound of Rosalie’s impatient voice coming from the kitchen.

“Joseph,” she yelled, “stop blowing that balloon—I don’t want you exerting yourself today!”

Bill resumed his reading, but was interrupted again by Rosalie who stood at the patio door saying that she was going with the children to Ann’s house to help prepare dinner. Bill, who had an appointment with a man at noon, would join her there later.

“Now don’t be late,” she called, as she turned to leave.

“I won’t,” he said, waving at the children, and saying nothing to Charles about the condition of the yard or the fact that the rabbits were running loose somewhere behind the small bushes and plants. Bill would deal with that tomorrow.

He read for another half hour, then got up to shave and get ready for his appointment. He was dressed casually on this Sunday, looking as if he were headed for the golf course. He wore light blue slacks and brown loafers, and glaring from under his gray sweater was a Day-Glo orange shirt. In the kitchen, after pouring himself a cup of coffee, he decided to telephone Brooklyn and say hello to his aunt Marion and his uncle Vincent Di Pasquale, with whom he would again be staying when he reappeared before the Kings County grand jury in a few weeks. That the phone was tapped was of no concern to him now, since he would be saying nothing of importance on this call; but after his aunt Marion had picked up the receiver, Bill heard a series of clicking sounds and various extensions being picked up, and he called out, “Hey, how many people are on this phone?”

“Hello,” his aunt said in a voice he could barely hear, and he also heard his cousin Linda on the bedroom extension in the Brooklyn house, with a child crying in the background.

“Is that you, son?” his aunt Marion asked, a childless woman who had always called him son. “Is that you?”

“Yes,” Bill said, “its me and the FBI on my end, and on your end its you and Linda and the baby and probably Aunt Jeanne upstairs and the New York detectives, right?”

“Hello,” said Linda, “how’s everybody there?”

“Fine,” Bill said. But before he could say much to Linda, his aunt Marion, a woman in her late sixties who kept abreast of nearly every trivial detail concerning the several relatives of the Bonannos, the Labruzzos, the Bonventres, and other kin and

compare

at home and overseas, had several things to say; among them was that her back ailment was improving, that Bill’s uncle’s cold was no better, that her nephew was doing well in art class, that the weather was chilly, that the television set needed a new tube, and other bits of vital information that Bill knew would fascinate the federal eavesdropper who was recording this conversation for posterity.

Mrs. Profaci stood at the stove cooking the snails, the lobsters, and preparing the ravioli, while Rosalie and Ann helped her, and Josephine sat in the living room with the men. Ann’s husband, Lou, was serving drinks, and the six children were running through the house, which was handsomely furnished and had a guitar near the fireplace that Lou used to play, along with the bass, when he sang professionally in small clubs where he was thought of as a second Russ Colombo. A relaxed, genial man approaching forty, Lou was now in business and sang only in the shower. But he appeared to have no regrets, was happily married and on good terms with his mother-in-law, delighted that another child was expected, and seemed to be unaware of the noise the children were now making as they scampered through the room out toward the patio. Lou noticed that his little son Lawrence was waving a toy pistol that Bill had given him; and while Lou knew that his wife did not like even toy guns in the house, he said nothing.

Bill was not yet at the house, nor was Tim Stanton. Tim would probably be late and they would not wait for him before starting dinner; but there was no question of going ahead without Bill. Until he arrived and greeted the assemblage, all would wait and talk among themselves, never thinking of sitting around the table without him, for in many subtle ways Bill was regarded as the head of the family.