i bc27f85be50b71b1 (133 page)

Read i bc27f85be50b71b1 Online

Authors: Unknown

VA"tUILAR SYSTEM AND HEMATOLOGY

433

SO. Sheppard KC. Nursing lvbnagemenr of Adulrs wirh Hemarologic Disorders. In PG Beare, Jl. Myers (cds), Adulr Ilealrh Nursing (3rd ed). Sr.

100llS: Moshy, 1998;670-711.

S 1. Reid ('D, ChJr3ch S, Luhin B (eds). Painful Evenrs. In Management and

Therapy of Sickle Cell Disease (3rd cd). National Institures of Health,

1995. Pub. 25-2117;,5.

52. Reid CD, Charach S, Lubin B (cds). Acme CheST Syndrome. In Managemenr and TIlerapy of Sickle Cell Disease (3rd ed). National Insmures of Ilealth, 1995. Puh. 25-2117;47.

53. Day SW, Wynn LW. Sickle Cell Pain and Hydroxyurea. Am J Nurs

2000; 100:34-39.

54. Bahior BM, Srosscl TP. llernarology: A Parhophysiologlcal Approach

(.lrd cd). New York: Churchill Livingsrone, 1994;359.

)5. levi M. De Jonge E. Current Management of Disseminated Intravascubr CoagulaTIon. Ilosp Pracr (Off Ed) 2000;35:59-66.

56. MarJ!tsann-Jacobs E. Nursing Care of Chenrs with Hematologic Disorders. In E Matassann-J.1Coh!t, Ji\'1 Black (eds), Medical-Surgical Nursing: Clinical Management for ContinUIty of Care (5th ed). Philadelphia:

S.llInders, 1997;1469-1532.

57. ThrombolyrlC Disorders. In AE Belcher, Blood Disorders. St. Louis:

Mosby, 1993; 112.

58. Ilorrell CJ, Rorhman J. ESTablishIng rhe eriology of rhrombocyropenia.

Nurse Pracr 2000;2.1:68-77.

S9. Warkenrln TE. Clinical Picture of Heparin-Induced Thrombocyropenia.

In Tl:-. \Xfarkcnnn, A Greinacher (cds), I leparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1999;43-73.

60. Jerdee AI. Ileparin-associated thrombocytopenia: nursing Implications.

em Care Nurse 1998; 18:38-43.

61. Gibbar-Clemenrs T, Shirrell 0, Dooley R, Smiley B. The challenge of

warfann rherapy. Am J Nurs 2000; 100:38-40.

62. llarknes, GA, DIOcher JR (cds). Medical-SurgIcal Nursing: Toral Pariem

Care (9rh ed). St. LouIS: Mosby, 1996;656.

63. Schroeder ML. Principles and Practice of Transfusion Medicine. In GR

Lee. J Foerster, J Lukens, et 31. (cds), Winrrobe's Clinical Hematology,

Vol. I ( I Olh cd). Balrimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999;8 J 7-874.

64. National Blood Resource Education Programs Transfusion Therapy

GUIdelines for Nurses. US Department of He:llth and Human Services,

National Insrirutes of Health. Seprember 1990.

65. Goodn1.l11 Cc. The Ilemarologic SYSTem. In: CC Goodman, WG Boisonnaliit (cds), Pathology: Implicarions for the Physical TherapISt. PhIladelphIa: Saunders, 1998;381.

7

Burns and Wounds

Michele P. West, Kimberly Knowlton,

and Marie Jarrell-Gracious

Introduction

Treating a patient with a major burn injury or other skin wound is

often a specialized area of physical therapy.' Physical therapists

should, however, have a basic understanding of normal and abnormal

skin integrity, including the etiology of skin breakdown and the factors that influence wound healing. The main objectives of this chapter are therefore to provide a fundamental review of the following:

1. The structure and function of the skin (integument)

2.

The evaluation and physiologic sequelae of burn injury,

including medical-surgical management and physical therapy

intervention

"'For the purpose of this chapter, an alteration in skin integrity secondary to a

burn injury is referred ro as a burn. Alteration in skin integrity from any other

etiology is referred to as a wound.

435

436 AClITE CARE HANDBOOK FOR PIIYSICAL TIIERAPISTS

3.

The etiology of different types of wounds and the process

of wound healing

4.

The evaluation and management of wounds, including

physical therapy intervention

Structure and function: Normal Integument

Stnlcture

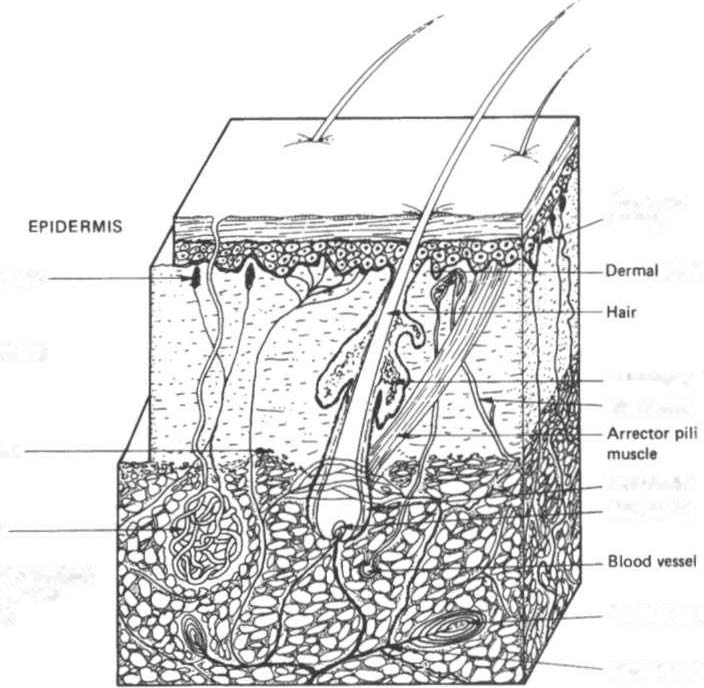

The integumentary system consists of the skin and its appendages

(hair and hair shafts, nails, and sebaceous and sweat glands),

which are located throughout the skin, as pictured in Figure 7-1.

Fr" nervI

endln91

TactlM! corpuscle

pipill.

DERMIS

S41bIceoullIl.nd

Blood_I

SubcutlllKlln

pepilll

H.ir follicle

H.ir pipill.

t ,land

SUBCUTANEOUS

CONNECTiVe

TISSUE

p.cini.n corpuscle

Nerve bundle

Figure 7-1. Three-dimensional representation of the skin and subcutaneous connective tissue layer showing the a"allgemellt of hair, glands, and blood vessels.

(With permission from N Palastallga, D Field, R Soames, e/ al. Anatomy and

Human Movement {2nd ed!. Oxford. UK: Butterworth-Heineman", 1989;49.}

BURNS AND WOUNDS 437

Skin is 0.5-4.0 mm thick and is composed of twO major layers: the

epidermis and the dermis. These layers are supported by subcutaneous tissue and fat that connect the skin to muscle and bone. The thin, avascular epidermis is composed mainly of cells containing

keratin. The epidermal cells are in different stages of growth and

degeneration. The thick, highly vascularized dermis is composed

mainly of connective tissue. Table 7- 1 lists the major contents of

each skin layer.

The skin has a number of clinically significant variations: ( 1) Men

have thicker skin than women; (2) rhe young and elderly have thinner

skin than adults'; and (3) the skin on various parts of the body varies

in thickness, number of appendages, and blood flow.' These variations affect the severity of a burn injury or skin breakdown, as well as the process of tissue healing.

Function

The incegument has seven major functionsJ:

I.

Temperature regulation. Body temperature is regula red by