In Arabian Nights (15 page)

Authors: Tahir Shah

'Ah, Señor Benito,' he said knowingly. He tapped a hand to

the reception's bell.

A submissive bellboy with large feet appeared.

'Ibrahim will show you,' he said.

As I plodded in Ibrahim's oversized footsteps, up the steep

slope towards the top of Tangier's medina, I cautioned myself to remember

how the Arab world proceeds. In Europe we bluster about, demanding answers

to direct questions, whereas in the East a far more circuitous and ancient

system is at work, where a little inane conversation can open gilded doors.

Almost a mile from the Continental, Ibrahim the bellboy froze

in his tracks. He turned ninety degrees to the left, to face an

ordinary door painted gloss white. He stuck out a hand. I

rewarded it appropriately.

'Señor Benito does not appreciate women,' he said.

I thanked him for the tip and tapped at the door. A dog

growled through the letterbox, and its din mingled with the

scent of figs. A firm hand struck the dog and the animal yelped

away. Then came the grinding sound of tired old feet approaching

slowly, a key turning and rusting hinges pressing back on

themselves.

The smell of figs became all the stronger when the door was

fully open. Señor Benito stepped through the frame and out into

the sunlight. His movements were made in slow motion, allowing

ample time for observation. He was a relic of old Tangier.

Dressed head to toe in pressed cream linen, with a fuchsia handkerchief

overflowing from his top pocket, his slender form

dazzled all who saw it. There was not an ounce of fat. His face

and all visible skin were as pale as his suit, almost dove grey. I

offered my hand. Señor Benito held the ends of my fingers for a

moment and squinted.

'

Bonjour

,' he said.

'I have come about the

Arabian Nights

.'

'Please come inside.'

Moving in slow motion, I followed the lines of cream linen

through the doorway, past a miniature sharp-toothed dog, into a

rambling villa, painted in off-white inside and out. The building

was less of a house and more like a temple, dedicated to

flamboyant indulgence and to phallic art. Every inch of space

was adorned with paintings, sketches, and sculptures, each one a

study on manhood.

The elderly Italian led the way into the salon, a well-proportioned

room adorned with phalluses great and small.

There were phalluses torn from Greek marbles, phalluses

portrayed in oils, sketched in charcoal, and on an elaborate

mantelpiece was a phallus crafted from wire mesh and parrot

feathers.

'We spoke on the telephone,' I said when we were seated in

the salon. It was a sentence designed to break the silence and to

cure my unease at the phallic decor.

Señor Benito smoothed a crease from his cream linen shirt.

He sauntered over towards the window, which was filled with

the winter blur of Gibraltar in the distance, and he turned.

'I have a nice bottle of port,' he said, 'a Sandeman 'sixty-three.'

He rolled back the northern hemisphere of an ornamental

globe, revealing a concealed drinks cabinet. His ashen fingers

fished out the bottle and poured two glasses.

Benito touched the port to his lips.

'Thank God for the Iberian Peninsula,' he said softly.

'Could I see the books?'

The old Italian jerked his chin towards a built-in set of shelves

at the far end of the room.

'Help yourself,' he said.

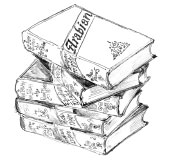

I scanned the bookcase. There must have been five hundred

books, half on phallic interests in every language of the world;

the other half dedicated to works of African exploration. At

ankle level, I found the set of ten volumes, the black cloth spines

bejewelled in gold,

Alf Layla wa Layla

, 'A Thousand Nights and

a Night'.

'Go on, take them out,' said the Italian.

I leaned forward and pulled out the books on either side.

Then, I carefully pushed my fingers behind the set and urged

them out one by one. The bindings were exquisite, the condition

near perfect. I opened the first book. It began with the name of

the Indian city Benares, the date in Roman numerals,

MDCCCLXXXV, 1885. After that, the words 'Printed by the

Kamashastra Society for Private Subscribers Only'.

'Two thousand copies were printed,' said Benito, topping up

our glasses. 'After the first ten volumes, Burton published six

more,

The Supplements

.'

'They were really printed in London, in Stoke Newington,' I

said.

The Italian put a hand to his heart.

'The censorship police,' he said dimly. 'They have hounded

good men before and since.'

'I don't understand how Abdul Hafiz the salesman found

you.'

Benito meandered over to the bookcase, stroking a hand over an

oversized Roman phallus as he went. He only stopped when he

was standing a foot away from me, his face three inches from mine.

'The Network,' he said.

I stepped back and he stepped forward, like a tango partner

following the lead. I was pinned to the bookcase.

'Are you a salesman as well, then?'

Benito blinked. 'A collector,' he said. 'And as such I am

connected to the Network.'

'What is the Network?'

'A group of people who link other people together,' he said. 'A

man with a want and another with a need.'

'Where is it, the Network?'

The Italian turned his palms upwards and stuck his arms out

to the side.

'It's all around us,' he said.

'But your need . . . to sell such a fine set of books as these?'

Benito glanced down at his white canvas shoes.

'It's a need inspired by a certain standard of living,' he said.

'Ask any collector and he will tell you.'

'Tell me what?'

'Tell you that there's no point having all this if you can't

afford a nice glass of port from time to time.'

After an hour of conversation I plucked up courage to enquire

the price of the books. I sensed Benito had lived in Tangier

since the old days, when Paul Bowles's salon attracted the great

writers of the Beat generation. As an adoptive Moroccan, he

knew the protocol. Unlike in the West, where the price is the

first thing you demand, in the East a transaction is far more

subtle. You first establish that you want to buy an object. You

inspect it and only then do you ask how much it might be.

The Italian didn't say the price at first.

He strolled back to the window, through two millennia of

phallic art, and took a good hard look at the rain.

'I've lived in this house since before you were born,' he said.

'Tangier is sleeping now. But back then it was wide awake. It

raged with life, with vitality, like a circus of the bizarre.' He put

out a hand and weighed his words. 'I heard from the Network

that a young man, a writer, was searching for one thing in life,'

he said. 'When asked to write it down on a piece of paper, he

wrote its name. Imagine how I felt . . . for that object you dream

of is sitting in my own home, gathering dust.'

Benito mumbled a price, a quarter of the market rate. I

thanked him and wrote out a cheque. He stepped slowly across

the room to a fine bureau with cabriole legs, opened one of the

miniature drawers, removed a scrap of crumpled paper, shuffled

back over and passed it to me. Written on it in my hand were the

words 'Richard Burton's

Arabian Nights

, Benares edition, 1885'.

The Italian collector looked out at the rain.

'Perhaps we could have lunch tomorrow,' he said in a whisper.

'I know a nice little place for fish.'

Opening the curtains next morning at the Continental, I was

dazzled by a flood of canary-yellow light. I held a hand to my

brow and spied the ferries straddling the Strait. Tangier is a

hybrid of Europe, Africa and the Arab world. It is a city of such

charm and sophistication that the people who reside there sometimes

forget their astonishing good fortune.

Eager to explore, I descended the steep steps and found the

desk clerk eating his breakfast on the counter. He grunted a

greeting, leaned down to open a cabinet below and pulled out a

pair of scratched sunglasses.

'We keep these for special guests,' he said with loathing.

I thanked him, bolstered at the thought of extra privilege, and

ambled out to the street. For thirty minutes I roved up and down

and up again until, after endless twists, turns and dead ends, I

came to the Grand Socco, Tangier's great square.

Poised at the edge of the old medina, the Grand Socco is a

cross-section of East and West. There are market stalls erupting

with produce, cafés packed with gritty no-nonsense men,

fountains, benches and a great mosque. There is a gate, too, leading

into the shadowed passages of the medina.

Burton had passed through it into the square during the

winter of 1885. He had come to seek fresh air, while working on

his epic translation. Part of the reason for his visit to Morocco

was to scout the country out. It had long been his dream to

become the British ambassador and the signs were good that his

appointment was imminent. With twenty-five years of experience

in the Consular Service, Burton had never been promoted,

despite regarding the Prime Minister himself as a personal

friend. He put his stalled diplomatic career down to a report he

had written four decades earlier, while in the employ of Sir

Charles Napier, on a Karachi male brothel touting a wide range

of eunuchs and young boys.

The first volume of

Arabian Nights

had appeared with much

media attention in the second week of September, three months

before Burton docked at Tangier. Each month or two another

volume was completed, then printed, and mailed directly to subscribers.

The early reviews had been mostly encouraging and no

subscribers had demanded their money back. Despite the good

reception, Burton must have been seething from an article in the

well-respected

Edinburgh Review

. Its correspondent Harry

Reeve had written: 'Probably no European has ever gathered

such an appalling collection of degrading customs and statistics

of vice. It is a work which no decent gentleman will long permit

to stand upon his shelves . . . Galland is for the nursery, Lane for

the study, and Burton for the sewers.'

Tangier's damp winter climate had brought on Burton's gout.

He didn't much appreciate the town, so it was perhaps just as

well that he was passed over for the position of ambassador. He

wrote to John Payne, a fellow translator of the

Arabian Nights

:

'Tangier is beastly, but not bad for work'. His description of the

Grand Socco is recorded in the tenth volume. He said that the

coffee-houses were all closed after a murder had occurred in one

of them. The usual clientele had been forced to drink their

refreshments and take their

kif

out on the street, despite the miserable

conditions.

It was there he found a storyteller plying his trade.

Characteristically harsh in his judgement, Burton was scathing

of the square, just as he was of the town in which it was found.

He wrote: 'It is a foul slope; now slippery with viscous mud, then

powdery with fetid dust, dotted with graves and decaying

tombs, unclean booths, gargottes and tattered tents, and frequented

by women, mere bundles of unclean rags . . .'

Of the storyteller, he was a little more approving: 'he speaks

slowly with emphasis, varying the diction with breaks of

animation, abundant action and the most comical grimace: he

advances, retires and wheels about, illustrating every point with

pantomime; and his features, voice and gestures are so expressive

that even Europeans who cannot understand a word of Arabic

divine the meaning of his tale. The audience stands breathless

and motionless surprising strangers by the ingeniousness and

freshness of feeling under their hard and savage exterior.'

Alas, there were no storytellers in evidence any longer. I

scanned the square, taking in the detail, wondering how the

atmosphere had changed in the century and more since Burton

had stood there. One significant alteration was the fabulous

Cinema Rif.