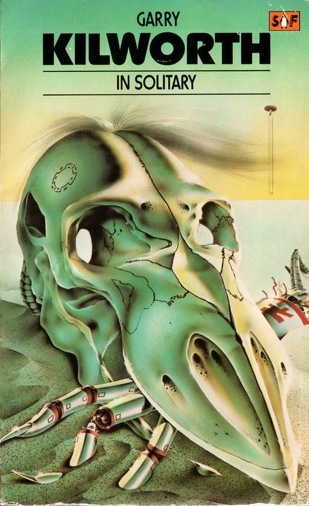

In Solitary

IN SOLITARY

Garry Kilworth

In the last years of the twentieth century (as Wells might have put it), Gollancz, Britain’s oldest and most distinguished science fiction imprint, created the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series. Dedicated to re-publishing the English language’s finest works of SF and Fantasy, most of which were languishing out of print at the time, they were – and remain – landmark lists, consummately fulfilling the original mission statement:

‘SF MASTERWORKS is a library of the greatest SF ever written, chosen with the help of today’s leading SF writers and editors. These books show that genuinely innovative SF is as exciting today as when it was first written.’

Now, as we move inexorably into the twenty-first century, we are delighted to be widening our remit even more. The realities of commercial publishing are such that vast troves of classic SF & Fantasy are almost certainly destined never again to see print. Until very recently, this meant that anyone interested in reading any of these books would have been confined to scouring second-hand bookshops. The advent of digital publishing has changed that paradigm for ever.

The technology now exists to enable us to make available, for the first time, the entire backlists of an incredibly wide range of classic and modern SF and fantasy authors. Our plan is, at its simplest, to use this technology to build on the success of the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series and to go even further.

Welcome to the new home of Science Fiction & Fantasy. Welcome to the most comprehensive electronic library of classic SFF titles ever assembled.

Welcome to the SF Gateway.

For Chantelle, Richard and Annette,

who already read me too well

… but there’s no cage to him

more than to the visionary his cell:

his stride is wildernesses of freedom:

the world rolls under the long thrust of his heel.

Over the cage floor the horizons come.

TED HUGHES,

The Jaguar

1. No member of the Human Race, born a native of the Planet Earth, may have contact with any other such native, by any medium, natural or otherwise, after the age of 170 months, except for the performance of mating.

2. No member of the Human Race under 170 months of age, born a native of the Planet Earth, may have contact with any male member of the same race.

The penalty for disobedience of the Soal Law is death.

Mating

From the Sennish of the Weyym:

…

and the sun shall inhale

…

Tangiia was building his mating canoe. It was a

Satawal, narrow and sleek with a slim outrigger for stability, for in the mating waters speed would be essential. It might mean the difference between a joyous union with a beautiful female, or violent death in the hands of a rival.

This was to be Tangiia’s third mating since the age of one hundred and eighty, for copulation with the Polynesian females was permitted only once every thirty-five months – a mandatory restriction imposed since the Soal first consolidated their victory over Earth exactly 70

2

+83 months previously.

The young man smoothed the bark with a piece of sandstone, running his free hand lovingly over the wood. He already had his fishing canoe, but that was outriggerless and purpose built. It needed too much draught for the sport of mating, being constructed to hold a bellyful of fish. The craft he needed now would be as light as a seabird, and would skim across the surface of the water hardly touching the waves along its arrow-straight course. That would be in the escape from the mêlée. During the capture, he would need to tack in and out of other boats and then run a female down. The seamanship of the females was as good as that of their male counterparts – sometimes better, because of their lithe movements, their spry bodies.

Tangiia remembered his first female as he sat working under the sun on the sugar-white sands of his small island. She had been brown and salty – and very experienced. Without Tangiia realizing she had drawn his attention and led him from the pack. At first he had been disappointed

– a young man likes an equally young woman with whom to share his prolonged lust – but he later understood that his lack of sexual knowledge would have left both partners not only disappointed, but prematurely exhausted. Although the first union with Keha had been a savage, clawing match, not without bloodletting on both sides, the controlled coaxing in the later movements, over the allowed five days, aroused him again and again to the performance of the act.

Keha had been small and agile, with bright, eager eyes: a woman of some 312 months. She had long nails which gave Tangiia some considerably painful but delightful moments at the dagger-point of ecstasy. He had enjoyed everything with her and did not want to exchange her, as was the custom, after the first two days. However, his ideas had not been shared by her, nor by the other man. There had been a fight in which his

lei o mano

had found the throat of his opponent, tearing an ugly wound in the man’s flesh.

This was the way of things. Occasionally fewer men returned from the mating than male children were born. The Soal had planned it so.

A bird floated overhead and Tangiia shouted and waved his fist at it.

‘Foul treader of wind, leave me.’

Birds had fallen into disrepute since the arrival of the conquering Soal, for the invaders resembled birds themselves, with pointed beak-like faces and a web of elastic skin joining the upper and lower limbs. They were approximately a metre tall – two thirds the height of an Earthman – and, to speak truthfully, were more like flying foxes than birds, but fine hair-like feathers covered their bodies. The feathers greyed with age, like hair, and gave the elderly Soal a ghostly, awful presence. Birds like gulls therefore, with white feathers, were especially despised by humans.

‘Go, go,’ shouted Tangiia, and picked up a stone from the beach ready to hurl it at the bird if it had the audacity to land within range.

It eyed the Polynesian warily, and then wheeled away on a warm current of air towards the sun.

‘He goes,’ said Tangiia, addressing his boat and waving his arm

contemptuously in the direction of the departing bird. Tangiia often spoke to his boat, as he spoke to the fish, and the wind, the trees and the rocks – and Tangiia was not mad. Man liked society and under the Soal his companions, apart from pets, were inanimate.

The last time Tangiia had mated, he had searched the temporarily white-scarred sea, covered with knifing craft, for Keha. For three years he had thought of nothing but Keha. She had visited his mind during the wild storms when he lay shivering with cold and fright and he had used the images of their threshings in the strapped-together canoes to chase away the demons from his mind. She had lain with him, in spirit, on the hot sands during the days when the sun draws the water from the seas and fills the air with its weight.

On the second voyage to the mating waters, held in the south of Oceania, the area surrounding north-eastern Ostraylea, Tangiia had dreamed of his woman. He followed a

kaveinga

, a star path, south-west towards his goal, watching the horizon during the night for one star after another to appear as a line to navigate by. When one star was too high, another rose to take its place on the horizon, and so on, until morning. Polynesians had been navigating thus for many thousands of months, using the deep ocean swells, imperceptible to a novice, to nudge the way during the day, and following the

kaveinga

during the dark hours. Polynesian navigators use no charts, no compasses, no instruments of man. They employ their senses and the natural ways of the universe: the star paths, the

panakenga

stars lying low on the horizon, the swells, currents, the direction of the flight of birds and the fascinating

te lapa

: underwater streaks of light that flash beneath the surface and point the way to the islands, said to have their origins in volcanic disturbances.

‘I am coming for you,’ Tangiia had called over the waves as he raced the dolphins towards Ostraylea.

‘I am coming for your brown body, you witch of seas. I come to taste the salt of your skin again, and kiss drops of water from your brows.’

He had called delightedly in the language of the Terrans: a language that had covered the globe before the Soal arrived and separated all men from their brothers. It was

the language taught him by his mother, until she left him, as was the Soal Law, at the age of one hundred and seventy, to be ever alone until death. Except, of course, for the brief periods of mating that were like bright jewels embedded in the blankness of his life.

Only a few of the Old Polynesian words remained: among those, the sacred words of the navigators that were prized for their inherent beauty.

Nearing Ostraylea, Tangiia had found himself in the midst of many other canoes and he gripped a shark-toothed

lei o mano

, relic of his ancestors, in one hand as he steered his canoe with the other. It was a time of great personal danger and he had been determined to have his Keha, if he was to die in the attempt.

The sails of the women’s mating canoes were seen coming from the east and a great moan of unlocked desire swept over the water as the thousands of small craft converged upon one another.

Tangiia’s eyes had been everywhere, anxiously searching, searching, for the bright blue sail of his lover. But there were many blue sails – and he never found Keha. After skimming past a dozen canoes he had finally struck a wave-skipping craft amidships in the crowded waters, had pitched forward and had landed at the feet of a beautiful, damp-eyed girl. She tore the cloth from his loins and soon he forgot his longing for Keha – her memory was lost in an explosion of athletic passion. If Keha had been an eager, blazing fire, Peloa was a volcano: a small, slim arc of thrusting lava-hot flesh with small conical breasts that burned their points into his own body.

Behind them, Ostraylea stood, the dark ring where the old waterline had once been, stark against the turquoise oceanic backdrop.

Behind that was one of the great mushroom towers. Around the mushroom tower high in the air, rolled a sky wheel – a transport of the Soal. It was inspecting its charge, apparently oblivious to the animalistic behaviour going on in the seas below it.

Suddenly it had paused, and then rolled closer to a leglike strut. It had seen something worth reporting – a fissure, like a lightning crack, upon the shell of the tower, which

appeared to be spreading. It was the cause of immediate and grave concern, and the wheel’s pilot contacted his base. Cracks were continually appearing on the Ostraylean tower. The day would come when it would need to be reinforced by more than minor repairs.

Banishment

…

its worlds slowly: the drawing in of a gentle breath

…

I faced the master, Klees of Brytan, as he trembled

with rage. A wave ran through his feathers like the wind over a field of long grass – a sign that I was truly in disgrace and that death should not be an unexpected punishment this time.