Influence: Science and Practice (3 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Click, Whirr

How ridiculous a mother turkey seems under these circumstances: She will embrace a natural enemy just because it goes cheep-cheep and she will mistreat or murder one of her chicks just because it does not. She acts like an automaton

whose maternal instincts are under the automatic control of that single sound. The ethologists tell us that this sort of thing is far from unique to the turkey. They have begun to identify regular, blindly mechanical patterns of action in a wide variety of species.

Called

fixed-action patterns

, they can involve intricate sequences of behavior, such as entire courtship or mating rituals. A fundamental characteristic of these patterns is that the behaviors comprising them occur in virtually the same fashion and in the same order every time. It is almost as if the patterns were recorded on tapes within the animals. When a situation calls for courtship, a courtship tape gets played; when a situation calls for mothering, a maternal behavior tape gets played.

Click

and the appropriate tape is activated;

whirr

and out rolls the standard sequence of behaviors.

The most interesting aspect of all this is the way the tapes are activated. When an animal acts to defend its territory for instance, it is the intrusion of another animal of the same species that cues the territorial-defense tape of rigid vigilance, threat, and, if need be, combat behaviors; however, there is a quirk in the system. It is not the rival as a whole that is the trigger; it is, rather, some specific feature, the

trigger feature

. Often the trigger feature will be just one tiny aspect of the totality that is the approaching intruder. Sometimes a shade of color is the trigger feature. The experiments of ethologists have shown, for instance, that a male robin, acting as if a rival robin had entered its territory, will vigorously attack nothing more than a clump of robin red breast feathers placed there. At the same time, it will virtually ignore a perfect stuffed replica of a male robin

without

red breast feathers (Lack, 1943). Similar results have been found in another species of bird, the bluethroat, where it appears that the trigger for territorial defense is a specific shade of blue breast feathers (Peiponen, 1960).

Before we enjoy too smugly the ease with which trigger features can trick lower animals into reacting in ways wholly inappropriate to the situation, we should realize two things. First, the automatic, fixed-action patterns of these animals work very well most of the time. For example, because only normal, healthy turkey chicks make the peculiar sound of baby turkeys, it makes sense for mother turkeys to respond maternally to that single cheep-cheep noise. By reacting to just that one stimulus, the average mother turkey will nearly always behave correctly. It takes a trickster like a scientist to make her tapelike response seem silly. The second important thing to understand is that we, too, have our preprogrammed tapes; and, although they usually work to our advantage, the trigger features that activate them can dupe us into playing the tapes at the wrong times.

1

1

Although several important similarities exist between this kind of automaticity in humans and lower animals, there are some important differences as well. The automatic behavior patterns of humans tend to be learned rather than inborn, more flexible than the lock-step patterns of the lower animals, and responsive to a larger number of triggers.

This parallel form of human automaticity is aptly demonstrated in an experiment by social psychologist Ellen Langer and her co-workers (Langer, Blank, & Chanowitz, 1978). A well-known principle of human behavior says that when we ask someone to do us a favor we will be more successful if we provide a reason. People simply like to have reasons for what they do (Bastardi & Shafir, 2000). Langer demonstrated this unsurprising fact by asking a small favor of people waiting in line to use a library copying machine: “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I’m in a rush?” The effectiveness of this request plus-reason was nearly total: 94 percent of those asked let her skip ahead of them in line. Compare this success rate to the results when she made the request only: “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?” Under those circumstances only 60 percent of those asked complied. At first glance, it appears that the crucial difference between the two requests was the additional information provided by the words

because I’m in a rush

. However, a third type of request tried by Langer showed that this was not the case. It seems that it was not the whole series of words, but the first one,

because

, that made the difference. Instead of including a real reason for compliance, Langer’s third type of request used the word

because

and then, adding nothing new, merely restated the obvious: “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I have to make some copies?” The result was that once again nearly all (93 percent) agreed, even though no real reason, no new information was added to justify their compliance. Just as the cheep-cheep sound of turkey chicks triggered an automatic mothering response from mother turkeys, even when it emanated from a stuffed polecat, so the word

because

triggered an automatic compliance response from Langer’s subjects, even when they were given no subsequent reason to comply.

Click

,

whirr

.

2

2

Perhaps the common “because . . . just because” response of children asked to explain their behavior can be traced to their shrewd recognition of the unusual amount of power adults appear to assign to the word

because

.

Although some of Langer’s additional findings show that there are many situations in which human behavior does not work in a mechanical, tape-activated way, she and many other researchers are convinced that most of the time it does (Bargh & Williams, 2006; Langer, 1989). For instance, consider the strange behavior of those jewelry store customers who swooped down on an allotment of turquoise pieces only after the items had been mistakenly offered at double their original price. I can make no sense of their behavior unless it is viewed in

click

,

whirr

terms.

The customers, mostly well-to-do vacationers with little knowledge of turquoise, were using a standard principle—a stereotype—to guide their buying: expensive = good. Much research shows that people who are unsure of an item’s quality often use this stereotype (Cronley et al., 2005). Thus the vacationers, who wanted “good” jewelry, saw the turquoise pieces as decidedly more valuable and desirable when nothing about them was enhanced but the price. Price alone had become a trigger feature for quality, and a dramatic increase in price alone had led to a dramatic increase in sales among the quality-hungry buyers.

3

3

In marketing lore, the classic case of this phenomenon is that of Chivas Regal Scotch Whiskey, which had been a struggling brand until its managers decided to raise its price to a level far above its competitors. Sales skyrocketed, even though nothing was changed in the product itself (Aaker, 1991). A recent brain-scan study helps explain why. When tasting the same wine, participants not only rated themselves as experiencing more pleasure if they thought it cost $45 versus $5, their brain centers associated with pleasure became more activated by the experience as well (Plassmann et al., 2008).

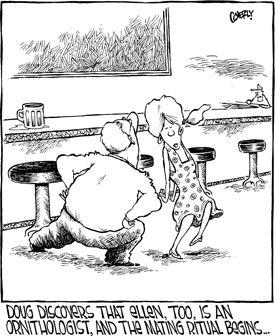

Cluck-Whirr

Human mating rituals aren’t actually as rigid as animals’. Still, researchers have uncovered impressive regularities in courtship patterns across many human cultures (Kenrick & Keefe, 1992). For instance, in personals ads around the world, women describe their physical attractiveness while men trumpet their material wealth (Buss & Kenrick, 1998).

Used by permission of Dave Coverly and Creators Syndicate, Inc.

READER’S REPORT 1.1

From a Management Doctoral Student

A man who owns an antique jewelry store in my town tells a story of how he learned the expensive = good lesson of social influence. A friend of his wanted a special birthday present for his fiancée. So, the jeweler picked out a necklace that would have sold in his store for $500 but that he was willing to let his friend have for $250. As soon as he saw it, the friend was enthusiastic about the piece. But when the jeweler quoted the $250 price, the man’s face fell, and he began backing away from the deal because he wanted something “really nice” for his intended bride.

When a day later it dawned on the jeweler what had happened, he called his friend and asked him to come back to the store because he had another necklace to show him. This time, he introduced the new piece at its regular $500 price. His friend liked it enough to buy it on the spot. But before any money was exchanged, the jeweler told him that, as a wedding gift, he would drop the price to $250. The man was thrilled. Now, rather than finding the $250 sales price offensive, he was overjoyed—and grateful—to have it.

Author’s note:

Notice that, as in the case of the turquoise jewelry buyers, it was someone who wanted to be assured of good merchandise who disdained the low-priced item. I’m confident that besides the “expensive = good” rule, there’s a flip side, “inexpensive = bad” rule that applies to our thinking as well. After all, in English, the word cheap doesn’t just mean inexpensive; it has come to mean inferior, too. A Japanese proverb makes this point eloquently: “There’s nothing more expensive than that which comes for free.”

Betting the Shortcut Odds

It is easy to fault the tourists for their foolish purchase decisions, but a close look offers a kinder view. These were people who had been brought up on the rule, “You get what you pay for” and who had seen that rule borne out over and over in their lives. Before long, they had translated the rule to mean expensive = good. The expensive = good stereotype had worked quite well for them in the past, since normally the price of an item increases along with its worth; a higher price typically reflects higher quality. So when they found themselves in the position of wanting

good turquoise jewelry but not having much knowledge of turquoise, they understandably relied on the old standby feature of cost to determine the jewelry’s merits (Rao & Monroe, 1989).

Although they probably did not realize it, by reacting solely to the price of the turquoise, they were playing a shortcut version of betting the odds. Instead of stacking all the odds in their favor by trying painstakingly to master each feature that indicates the worth of turquoise jewelry, they were counting on just one—the one they knew to be usually associated with the quality of any item. They were betting that price alone would tell them all they needed to know. This time, because someone mistook a “½” for a “2,” they bet wrong. In the long run, over all the past and future situations of their lives, betting those shortcut odds may represent the most rational approach possible.

In fact, automatic, stereotyped behavior is prevalent in much human action, because in many cases, it is the most efficient form of behaving (Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 1996), and in other cases it is simply necessary (Bodenhausen, Macrae, & Sherman, 1999; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). You and I exist in an extraordinarily complicated environment, easily the most rapidly moving and complex that has ever existed on this planet. To deal with it, we

need

shortcuts. We can’t be expected to recognize and analyze all the aspects in each person, event, and situation we encounter in even one day. We haven’t the time, energy, or capacity for it. Instead, we must very often use our stereotypes, our rules of thumb, to classify things according to a few key features and then to respond without thinking when one or another of these trigger features is present.