Influence: Science and Practice (46 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Chapter 7

Scarcity

The Rule of the Few

The way to love anything is to realize that it might be lost.

—G. K. Chesterton

T

HE CITY OF MESA, ARIZONA, IS A SUBURB IN THE PHOENIX AREA

where I live. Perhaps the most notable features of Mesa are its sizable Mormon population—next to Salt Lake City, the largest in the world—and a huge Mormon temple located on exquisitely kept grounds in the center of the city. Although I had appreciated the landscaping and architecture from a distance, I had never been interested enough in the temple to go inside, until the day I read a newspaper article that told of a special inner sector of Mormon temples to which no one has access but faithful members of the church. Even potential converts must not see it; however, there is one exception to the rule. For a few days immediately after a temple is newly constructed, non-members are allowed to tour the entire structure, including the otherwise restricted section.

The newspaper story reported that the Mesa temple had been recently refurbished and that the renovations had been extensive enough to classify it as “new” by church standards. Thus, for the next several days only, non-Mormon visitors could see the temple area traditionally banned to them. I remember quite well the effect this article had on me: I immediately resolved to take a tour; but when I phoned a friend to ask if he wanted to come along, I came to understand something that changed my decision just as quickly.

After declining the invitation, my friend wondered why

I

seemed so intent on a visit. I was forced to admit that, no, I had never been inclined toward the idea of a temple tour before, that I had no questions about the Mormon religion I wanted answered, that I had no general interest in church architecture, and that I expected to find nothing more spectacular or stirring than what I might see at a number of other churches in the area. It became clear as I spoke that the special lure of the temple had a sole cause: If I did not experience the restricted sector soon, I would never again have the chance. Something that, on its own merits, held little appeal for me had become decidedly more attractive merely because it was rapidly becoming less available.

Less Is Best and Loss Is Worst

I count myself far from alone in this weakness. Almost everyone is vulnerable to the scarcity principle in some form. Take as evidence the experience of Florida State University students who, like most undergraduates when surveyed, rated the quality of their campus cafeteria food unsatisfactory. Nine days later, according to a second survey, they had changed their minds. Something had happened to make them like their cafeteria’s food significantly better than before. Interestingly, the event that caused them to shift their opinions had nothing to do with the quality of the food service, which had not changed a whit. But its availability had. On the day of the second survey, the students had learned that, because of a fire, they could not eat at the cafeteria for the next two weeks (West, 1975).

Collectors of everything from baseball cards to antiques are keenly aware of the scarcity principle’s influence in determining the worth of an item. As a rule, if an

item is rare or becoming rare, it is more valuable. Especially enlightening on the importance of scarcity in the collectibles market is the phenomenon of the “precious mistake.” Flawed items—a blurred stamp or double-struck coin—are sometimes the most valued of all. Thus, a stamp carrying a three-eyed likeness of George Washington is anatomically incorrect, aesthetically unappealing, and yet highly sought after. There is instructive irony here: Imperfections that would otherwise make for rubbish make for prized possessions when they bring along an abiding scarcity.

Since my own encounter with the scarcity principle—

that opportunities seem more valuable to us when they are less available

—I have begun to notice its influence over a whole range of my actions. For instance, I routinely will interrupt an interesting face-to-face conversation to answer the ring of an unknown caller. In such a situation, the caller possesses a compelling feature that my face-to-face partner does not—potential unavailability. If I don’t take the call, I might miss it (and the information it carries) for good. Never mind that the present conversation may be highly engaging or important—much more than I could reasonably expect an average phone call to be. With each unanswered ring, the phone interaction becomes less retrievable. For that reason and for that moment, I want it more than the other conversation.

People seem to be more motivated by the thought of losing something than by the thought of gaining something of equal value (Hobfoll, 2001). For instance, college students experienced much stronger emotions when asked to imagine losses as opposed to gains in their romantic relationships or in their grade point averages (Ketelaar, 1995). Especially under conditions of risk and uncertainty, the threat of potential loss plays a powerful role in human decision making (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981; De Dreu & McCusker, 1997). Health researchers Alexander Rothman and Peter Salovey have applied this insight to the medical arena, where individuals are frequently urged to undergo tests to detect existing illnesses (e.g., mammography procedures, HIV screenings, cancer self-examinations). Because such tests involve the risk that a disease will be found and the uncertainty that it will be cured, messages stressing potential losses are most effective (Rothman & Salovey, 1997; Rothman, Martino, Bedell, Detweiler, & Salovey, 1999). For ex-ample, pamphlets advising young women to check for breast cancer through self-examinations are significantly more successful if they state their case in terms of what stands to be lost rather than gained (Meyerwitz & Chaiken, 1987). In the world of business, research has found that managers weigh potential losses more heavily than potential gains (Shelley, 1994). Even our brains seem to have evolved to protect us against loss in that it is more difficult to disrupt good decision-making regarding loss than gain (Weller et al., 2007).

Limited Numbers

With the scarcity principle operating so powerfully on the worth we assign things, it is natural that compliance professionals will do some similar operating of their own. Probably the most straightforward use of the scarcity principle occurs in the “limited-number” tactic in which a customer is informed that a certain product is in short supply that cannot be guaranteed to last long. During the time I was researching compliance strategies by infiltrating various organizations, I saw the limited-number tactic employed repeatedly in a range of situations: “There aren’t more than five convertibles with this engine left in the state. And when they’re gone, that’s it, ’cause we’re not making ’em anymore.” “This is one of only two unsold corner lots in the entire development. You wouldn’t want the other one; it’s got a nasty east-west exposure.” “You may want to think seriously about buying more than one case today because production is backed way up and there’s no telling when we’ll get any more in.”

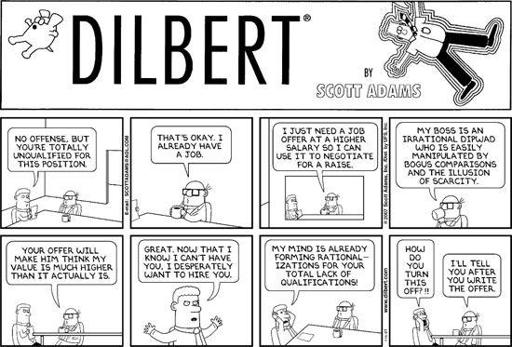

Hirer Value

DILBERT:

© Scott Adams. Distributed by United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

Sometimes the limited-number information was true, sometimes it was wholly false. In each instance, however, the intent was to convince customers of an item’s scarcity and thereby increase its immediate value in their eyes. I admit to developing a grudging admiration for the practitioners who made this simple device work in a multitude of ways and styles. I was most impressed, however, with a particular version that extended the basic approach to its logical extreme by selling a piece of merchandise at its scarcest point—when it seemingly could no longer be had. The tactic was played to perfection in one appliance store I investigated where 30 to 50 percent of the stock was regularly listed on sale. Suppose a couple in the store seemed, from a distance, to be moderately interested in a certain sale item. There are all sorts of cues that tip off such interest—closer-than-normal examination of the appliance, a casual look at any instruction booklets associated with the appliance, discussions held in front of the appliance, but no attempt to seek out a salesperson for further information. After observing the couple so engaged, a salesperson might approach and say, “I see you’re interested in this model here, and I can understand why: it’s a great machine at a great price. But, unfortunately, I sold it to another couple not more than 20 minutes ago. And, if I’m not mistaken, it was the last one we had.”

The customers’ disappointment registers unmistakably. Because of its lost availability, the appliance suddenly becomes more attractive. Typically, one of the customers asks if there is any chance that an unsold model still exists in the store’s back room or warehouse or other location. “Well,” the salesperson allows, “that is possible, and I’d be willing to check. But do I understand that this is the model you want and if I can get it for you at this price, you’ll take it?” Therein lies the beauty of the technique. In accord with the scarcity principle the customers are asked to commit to buying the appliance when it looks least available and therefore most desirable. Many customers do agree to purchase at this singularly vulnerable time. Thus, when the salesperson (invariably) returns with the news that an additional supply of the appliance has been found, it is also with a pen and sales contract in hand. The information that the desired model is in good supply actually may make some customers find it less attractive again (Schwarz, 1984), although by then the business transaction has progressed too far for most people to renege. The purchase decision made and committed to publicly at an earlier, crucial point still holds. They buy.

READER’S REPORT 7.1

From a Woman Living in Upstate New York

One year I was shopping for Christmas gifts when I ran across a black dress that I liked for myself. I didn’t have the money for it because I was buying gifts for other people. I asked the store to please set it aside until I could return on Monday after school with my mom to show her the dress. The store said they couldn’t do that.

I went home and told my mom about it. She told me that if I liked the dress, she would loan me the money to get it until I could pay her back. After school on Monday, I went to the store only to find the dress was gone. Someone else had bought it. I didn’t know until Christmas morning that while I was in school my mom went to that store and bought the dress I had described to her. Although that Christmas was many years ago, I still remember it as one of my favorites because after first thinking that I’d lost that dress, it became a valued treasure for me to have.

Author’s note:

It is worth asking what it is about the idea of loss that makes it so potent in human functioning. One prominent theory accounts for the primacy of loss over gain in evolutionary terms. If one has enough to survive, an increase in resources will be helpful but a decrease in those same resources could be fatal. Consequently, it would be adaptive to be especially sensitive to the possibility of loss (Haselton & Nettle, 2006).

Time Limits

Related to the limited-number technique is the “deadline” tactic in which some official time limit is placed on the customer’s opportunity to get what the compliance professional is offering. Much like my experience with the Mormon temple’s inner sanctum, people frequently find themselves doing what they wouldn’t much care to do simply because the time to do so is running out. The adept merchandiser makes this tendency pay off by arranging and publicizing customer deadlines that generate interest where none may have existed before. Concentrated instances of this approach often occur in movie advertising. In fact, I recently noticed that one theater owner, with remarkable singleness of purpose, had managed to invoke the scarcity principle three separate times in just five words of copy: “Exclusive, limited engagement ends soon!”