John Quincy Adams (41 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

In leading the fight against recognition of Texan independence, he also found a perfect weapon against the Gag Rule: “Mr. Chairman,” he thundered. “Are you ready for all these wars? A Mexican war? A war with Britain, if not with France? A general Indian war? A servile war? And, as an inevitable consequence of them all, a civil war?” The South and South-west,

he warned, would be “the battlefield upon which the last great conflict must be fought between slavery and emancipation.”

he warned, would be “the battlefield upon which the last great conflict must be fought between slavery and emancipation.”

I avow it as my solemn belief that the annexation of an independent foreign power to this government would be

ipso facto

a dissolution of this Union. . . . The question is whether a foreign nation [Texas] . . . a nation damned to everlasting fame by the reinstitution of that detested system of slavery, after it had been abolished within its borders, should be admitted into union with a nation of freemen. For, Sir, that name, thank God, is still ours!

33

ipso facto

a dissolution of this Union. . . . The question is whether a foreign nation [Texas] . . . a nation damned to everlasting fame by the reinstitution of that detested system of slavery, after it had been abolished within its borders, should be admitted into union with a nation of freemen. For, Sir, that name, thank God, is still ours!

33

“Take your seat!” the Speaker ordered, trying to apply the Gag Rule, but John Quincy shouted back, “Am I gagged? Am I gagged?” He then appealed to the House membership, and it overruled the Speaker to ensure open debate on the Texas questionâand once they opened the debate on Texas, they automatically reopened the debate on slavery. “The annexation of Texas,” John Quincy thundered in response, “and the proposed war with Mexico are all one and the same thing.”

34

34

Humiliated by John Quincy's rhetorical tactics, southerners began to shout, “Expel him!” whenever he spoke. “Expel him!” they repeated, as he continuedâsometimes prolonging his diatribes against slavery for hours and, in one instance, for parts of fifteen days.

John Quincy went beyond the halls of Congress to the American people and became a national presence, a force for justice and progress that he had never been beforeâeven as President of the United States. Invited to speak throughout the Northeast and parts of the West, he used traditional July 4 orations, along with eulogies on the deaths of the Marquis de Lafayette and James Madison, to echo the words of George Washington and other Founding Fathers. Although silent on slavery, all had inveighed against involvement in foreign wars, and John Quincy now connected the two issues. John Quincy appealed to church leaders, calling slavery “a sin before the sight of God,” and they, in turn, formed peace societies that inundated Congress and the White House with petitions signed by tens of

thousands of Americans opposed to war with Mexico. State legislatures in Vermont, Michigan, Ohio, and Massachusetts passed resolutions supporting John Quincy's war against warâand against recognition of Texas. Southerners in Congress, however, proved too strong, and after both houses voted in favor of recognizing Texan independence, President Jackson agreed and appointed a chargé d'affaires. As John Quincy had predicted, a petition for U.S. annexation of Texas followed recognition, but, in the face of the growing antiwar movement, Jackson, nearing the end of his presidency, rejected it, refusing to risk certain war with Mexico.

thousands of Americans opposed to war with Mexico. State legislatures in Vermont, Michigan, Ohio, and Massachusetts passed resolutions supporting John Quincy's war against warâand against recognition of Texas. Southerners in Congress, however, proved too strong, and after both houses voted in favor of recognizing Texan independence, President Jackson agreed and appointed a chargé d'affaires. As John Quincy had predicted, a petition for U.S. annexation of Texas followed recognition, but, in the face of the growing antiwar movement, Jackson, nearing the end of his presidency, rejected it, refusing to risk certain war with Mexico.

By then, Andrew Jackson had decided to follow the precedent of earlier Presidents and cede his office after two terms, and the Democratic Party nominated Vice President Van Buren of New York as their candidate to succeed Jackson. Van Buren had used his presidency of the Senate to court antiabolition sentiment in Congress, and in December 1736, he scored an overwhelming victory over three other candidates, including Daniel Webster. John Quincyâby then towering over his House colleagues as champion of national interestsâeasily won reelection to the House without a party designation and without campaigning. Approaching seventy and feeling the effects of his age, he returned to Congress in 1737 determined to save his nation from destruction.

Having pledged to “tread . . . in the footsteps of President Jackson,” President Van Buren confirmed Jackson's rejection of Texas's annexation, thus temporarily setting aside one of the major controversies facing the new Congress but ceding center stage to abolition again. The House immediately reinstituted the Gag Rule, and John Quincy struck back, presenting more than two hundred petitions remonstrating against the Gag Rule as a violation of the Constitution, of the rights of his constituents, “and of my right of freedom of speech as a member of this House.” The House responded with what he described as “war whoops of âOrder!'”

35

35

Day after day, the struggle continued. During the 1837â1838 session alone, the American Antislavery Society sent the House 130,200 petitions, with untold thousands of names, to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia; 32,000 petitions to abolish the Gag Rule; 21,200 to forbid

slavery in U.S. territories; 22,160 against admitting any new slave states; and 23,160 to abolish the slave trade between states.

36

Whenever John Quincy tried to comment on a resolution, the Speaker interrupted: “The gentleman from Massachusetts,” he shouted, “must answer aye or no and nothing else! Order!”

slavery in U.S. territories; 22,160 against admitting any new slave states; and 23,160 to abolish the slave trade between states.

36

Whenever John Quincy tried to comment on a resolution, the Speaker interrupted: “The gentleman from Massachusetts,” he shouted, “must answer aye or no and nothing else! Order!”

“I refuse to answer,” John Quincy fired back, “because I consider all proceedings of the Houseâ”

Again, the Speaker interrupted him with shouts of “Order! Order!”

John Quincy slumped into his seat in response, but his voice persisted: “âa direct violation of the Constitution!”

37

37

Around him came the cries, “Expel him! Expel him!” from southerners, whose numbers grew ever greater with the expansion of the slave population, which could not vote. Slaves had increased the number of southern members of the House by 35 percentâenough to expel John Quincy, and they now prepared to do just that.

CHAPTER 14

Freedom Is the Prize

Washington's oppressive summer heat forced Congress to recess before proceeding against John Quincy Adams in 1839, and he was able to return home to the cool breezes of Quincy Bay with Louisa and their two “angelic” granddaughters, the children of their son John II. What should have been a summer of joy, however, proved a season of heartbreak, when the older girl, nine-year-old Fanny, contracted diphtheria. Often shrieking from the pain gripping her throat, she spent weeks in agony before dying in the fall. Her death devastated John Quincy and left him pessimistic about his own future, as he faced expulsion from the House. “I fear I have done little good in the world,” he moaned, “and my life will end in disappointment of the good I would have done had I been permitted.”

1

1

After burying Fanny, the Adamses returned to Washington and brought their surviving granddaughter and her mother to live in their house on F Street. Their presence brought new joy into Louisa's otherwise drab life and even sparked a smile or two on John Quincy's often dour faceâespecially when Mary Louisa turned to her “Grandpappa” for help in algebra and logarithms. He often encouraged her to copy poemsâone of them a favorite

of his by Scottish poet William Russell, whose “Ode to Fortitude”

2

asked, “Can noble things from base proceed?”

of his by Scottish poet William Russell, whose “Ode to Fortitude”

2

asked, “Can noble things from base proceed?”

“Not so the lion springs,” John Quincy often answered his grandchild, “not so the steed; Nor from the vulgar tenants of the grove, sublimed with pageant-fire, the strong-pounced bird of Jove.”

3

3

In addition to Mary Louisa, the Adamses had grandsons to fuss over. One of them, Charles Francis Adams II, would long remember his grandfather's continually herding the grandchildren through a canyon of books into his study, and his younger brother Henry Adams would remember his grandfather as “an old man of seventy-five or eighty who was always friendly and gentle, but . . . always called âthe President,'” while Louisa was “the Madam.”

Author of the renowned autobiography

The Education of Henry Adams

, Henry Adams passed summers with his grandparents at Quincy until he was twelve years old and would remember throughout his life “the effect of the back of the President's head as he sat in his pew on Sundays.”

The Education of Henry Adams

, Henry Adams passed summers with his grandparents at Quincy until he was twelve years old and would remember throughout his life “the effect of the back of the President's head as he sat in his pew on Sundays.”

It was unusual for boys to sit behind a President grandfather and to read over his head the tablet in memory of a President great-grandfather who had pledged “his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor” to secure the independence of his country and so forth. . . . The Irish gardener once said, “You'll be thinkin' you'll be President too.”

4

4

When Congress reconvened in December 1839, elections had divided the House evenly, and disorder attended every effort to establish committee memberships. Deadlocked and facing legislative paralysis, Congress turned to the only man every member trusted, regardless of what they felt about his politics or him personallyâand some genuinely hated him. But John Quincy Adams was the man who represented the whole nation, and above all else, they knew him to be that rarest of colleagues: an honest man and patriot. Astonished by the suddenâand almost universalâembrace, John Quincy accepted the invitation and served as Speaker pro tem long enough to work out committee memberships. When he suc-ceeded

to everyone's satisfaction and stepped down from his leadership role, they immediately turned on him again, reimposed the Gag Rule, and overrode his angry demands to repeal it.

to everyone's satisfaction and stepped down from his leadership role, they immediately turned on him again, reimposed the Gag Rule, and overrode his angry demands to repeal it.

Â

John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams's grandson Henry Adams, seen here as a Harvard undergraduate, had warm memories of his grandparents that he related in his autobiography,

The Education of Henry Adams. (NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

The Education of Henry Adams. (NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

Just then, however, his friend Ellis Gray Loring, a prominent Massachusetts attorney and outspoken opponent of slavery, drew John Quincy's attention away from the turmoil in Congress with some startling legal documents. In January 1840, a federal district court in New Haven, Connecticut, was about to hear the case of thirty-six Africans who had been prisoners on the slave ship

Amistad

off the coast of Cuba. Led by a Congolese chief named Cinque, they had broken their chains, killed the captain and three crewmen, and overpowered the white crew. Knowing nothing of navigation, they ordered the white crew to sail them to Africa, and by day the crew complied. At night, however, the crewmen reversed course and eventually sailed

into American waters, where an American frigate seized the ship and took it to New London, Connecticut. Officials there arrested the Africans and charged them with piracy and murder, but a number of legal questions complicated the case: Were the Africans propertyâthat is, slavesâto be returned to their owners? Or were they people, to be released on habeas corpus and later tried for piracy and murder? And finally, did the United States have jurisdiction? Or should U.S. authorities release the prisoners to Spanish authorities to do with as they wished under Spanish law?

Amistad

off the coast of Cuba. Led by a Congolese chief named Cinque, they had broken their chains, killed the captain and three crewmen, and overpowered the white crew. Knowing nothing of navigation, they ordered the white crew to sail them to Africa, and by day the crew complied. At night, however, the crewmen reversed course and eventually sailed

into American waters, where an American frigate seized the ship and took it to New London, Connecticut. Officials there arrested the Africans and charged them with piracy and murder, but a number of legal questions complicated the case: Were the Africans propertyâthat is, slavesâto be returned to their owners? Or were they people, to be released on habeas corpus and later tried for piracy and murder? And finally, did the United States have jurisdiction? Or should U.S. authorities release the prisoners to Spanish authorities to do with as they wished under Spanish law?

Â

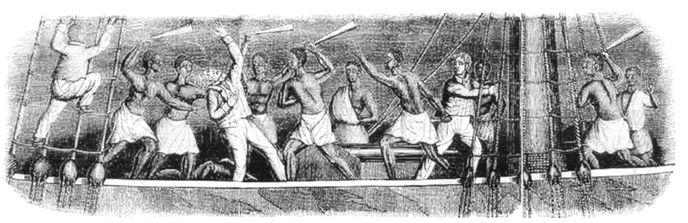

Killing of the captain of the

Amistad

by a band of free Africans kidnapped by slavers and transported to Cuba to be sold as slaves. John Quincy Adams pleaded for their freedom before the U.S. Supreme Court.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Amistad

by a band of free Africans kidnapped by slavers and transported to Cuba to be sold as slaves. John Quincy Adams pleaded for their freedom before the U.S. Supreme Court.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The district court pronounced the Negroes to have been free men, whom slavers had kidnapped and transported to Cuba illegallyâunder Spanish as well as American law. It deemed the killings justified as legitimate acts of self-defense against the kidnappers and ordered the Africans turned over to the President of the United States for transport back to their native land at American government expense.

Having already alienated southerners by rejecting Texas annexation, President Van Buren was unwilling to provoke his southern constituency further and ordered the district attorney to appeal the lower court order to the circuit court. The circuit court upheld the district court and forced government prosecutors to take the case still higher to the U.S. Supreme Court. By then, however, abolitionists who had paid for the legal defense of the

Amistad

Africans ran out of funds, and all but two attorneys quit. Only Loring and Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandson of Revolutionary War

hero Roger Sherman, agreed to remain on the case pro bono. They turned to John Quincy to join their appeal to the Supreme Courtâalso without a feeâand he agreed.

Amistad

Africans ran out of funds, and all but two attorneys quit. Only Loring and Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandson of Revolutionary War

hero Roger Sherman, agreed to remain on the case pro bono. They turned to John Quincy to join their appeal to the Supreme Courtâalso without a feeâand he agreed.

Other books

Caroline and the Captain: A Regency Novella by Maggi Andersen

Going Gray by Spangler, Brian

Silent Witnesses by Nigel McCrery

Misty Blue by Dyanne Davis

City of Bones by Cassandra Clare

So Much It Hurts by Monique Polak

Train Man by Nakano Hitori

Deja Blue by Walker, Robert W

Black Arts: A Jane Yellowrock Novel by Hunter, Faith

Mirror dance by Lois McMaster Bujold