John Quincy Adams (44 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

“Under this state of things,” he spoke, staring at the southerners, “so far from its being true that the states where slavery exists have the exclusive management of the subject, not only the President of the United States but the commander of the army has power to order the universal emancipation of the slaves.”

30

30

Years later, Henry Wise would characterize John Quincy as the “acutest, astutest, archest enemy of southern slavery that ever existed . . . and his prophecies have been fulfilled . . . far faster and more fearfully . . . than ever he anticipated.”

31

31

John Quincy's triumph in the House provoked the usual hate mail, but the number of his supporters swelled across the nation, with one Pennsylvanian writing, “You are honored, old manâthe hearts of a hundred thousand Pennsylvanians are with you.” Another called him “the only public man in the land who possesses the union of courage with virtue.” Poet John Greenleaf Whittier prayed, “God bless thee, and preserve thee.”

32

Even those who had opposed the aggressive tactics of abolitionists now wrote, “I am no abolitionist, yet I am in favor of the emancipation of the colored race.”

33

32

Even those who had opposed the aggressive tactics of abolitionists now wrote, “I am no abolitionist, yet I am in favor of the emancipation of the colored race.”

33

His popularity exceeded that of the President, and had he defended his beliefs as aggressively when he was President, he would certainly never have suffered the humiliation of defeat in his run for reelection. Few Americans knew or understood him as President; almost every American now knew and understood himâindeed, revered himâafter his battle in Congress, and millions now listened to every word of the Sage of Quincy. Hundreds lined up to see him, to hear his words, to try to talk to him as he walked about Washington, striding to and from the Capitol each day. Luminaries from all parts of the United States, Britain, and Europe called at his home. Charles Dickens and his wife stopped for lunch, and Dickens asked for

John Quincy's autograph before leaving. John Quincy had emerged as one of the most celebrated and beloved personages in the Western world.

John Quincy's autograph before leaving. John Quincy had emerged as one of the most celebrated and beloved personages in the Western world.

In 1843, his son Charles Francis, by then a member of the Massachusetts state legislature, introduced a resolution calling for a constitutional amendment abolishing the right of slave states to count five slaves as equal to three white men in determining representation in the House of Representatives. With deep pride, John Quincy in turn introduced his son's amendment in the Houseâwhich ignored it. After he won reelection in 1844, however, the House could not ignore his resolution abolishing the Gag Rule. Indeed, it passed it immediately, 105â80, ending the great battle he had fought for freedom of debate in Congress, freedom of speech generally, and the right of citizens to petition their government. It was the first victory the North would win against the South and the slaveocracy.

“Blessed, ever blessed be the name of God,” John Quincy exulted afterwards.

34

34

Riding his wave of popularity, he set off to promote national interest in science and education by accepting an invitation to speak at ceremonies laying the cornerstone of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society's observatory. It was an arduous trip for an old man, but one with opportunities to promote science educationâespecially his “lighthouses of the sky”âacross a broad territory.

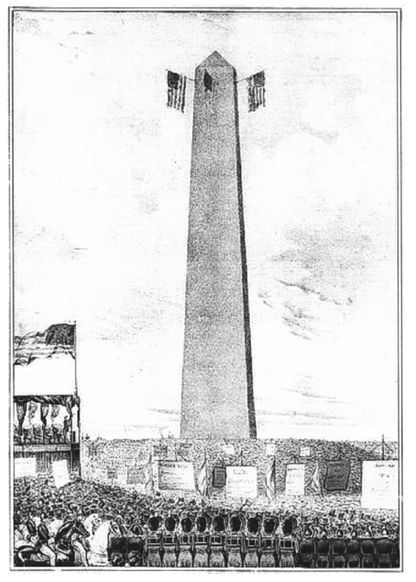

He had no sooner received his invitation to speak in Cincinnati when another invitation arrivedâthis one to attend the long-anticipated completion of the Bunker's Hill Monument, commemorating the battle he had witnessed as a seven-year-old with his mother in 1775. When, however, he learned that President John Tyler “and his cabinet of slave-drivers” would also attend, he refused. “How,” he asked, “could I have witnessed this without an unbecoming burst of indignation or of laughter? John Tyler is a slave-monger.”

With the association of the thundering cannon, which I heard, and the smoke of burning Charlestown, which I saw on that awful day, combined with this pyramid of Quincy granite and John Tyler's nose, with a shadow

outstretching that of the monumental column, I stayed at home and visited my seedling trees and heard the cannonades, rather than watch the President at dinner in Faneuil Hall swill like swine and grunt about the rights of man.

35

outstretching that of the monumental column, I stayed at home and visited my seedling trees and heard the cannonades, rather than watch the President at dinner in Faneuil Hall swill like swine and grunt about the rights of man.

35

Â

Celebration at the completion of the Bunker's Hill Monument in Charlestown in June 1843. Invited to be the principal orator, John Quincy Adams refused to attend because of the presence of President John Tyler, a Virginia slaveholder and fierce opponent of abolition.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Shortly after the Bunker's Hill ceremonies, John Quincy left for Cincinnati, fulfilling his every lust to experience the latest scientific advances in transportationâsteam-driven trains to Albany, New York, and across New York State to Buffalo, then steamboats across Lake Erie to Cleveland and

down the Ohio Canal to Columbus. At every stop, cheering crowds welcomed him as a hero. The “firing of cannon, ringing of bells . . . and many thousand citizens” greeted him in Schenectady, New York; thousands moreâand the governorâwaited in Albany. A torchlight parade led his way through Utica, New York, climaxing with a photographer taking a daguerreotype of him with General Tom Thumb. “Multitudes of citizens” cheered in Cleveland, and in Columbus, he confessed, he had never witnessed “so much humanity.” In Dayton, two military companies awaited to escort him, along with “an elegant open barouche in which I took a seat and thus in triumphal procession we entered the city,” where “a vast multitude” awaited. He reached Cincinnati on November 8 and, to his enormous satisfaction, learned that the city had named the hill on which its new observatory would stand Mount Adams.

down the Ohio Canal to Columbus. At every stop, cheering crowds welcomed him as a hero. The “firing of cannon, ringing of bells . . . and many thousand citizens” greeted him in Schenectady, New York; thousands moreâand the governorâwaited in Albany. A torchlight parade led his way through Utica, New York, climaxing with a photographer taking a daguerreotype of him with General Tom Thumb. “Multitudes of citizens” cheered in Cleveland, and in Columbus, he confessed, he had never witnessed “so much humanity.” In Dayton, two military companies awaited to escort him, along with “an elegant open barouche in which I took a seat and thus in triumphal procession we entered the city,” where “a vast multitude” awaited. He reached Cincinnati on November 8 and, to his enormous satisfaction, learned that the city had named the hill on which its new observatory would stand Mount Adams.

His last major stop was in Pittsburgh, which gave him a “magnificent reception” before he helped lay the cornerstone for still another astronomical observatory “to promote the cause of science.” He returned to Washington in November, after traveling across Pennsylvania, with brass bands, public officials, and huge crowds cheering his visit in every community. Speaking at every stop, however, took its toll, and he contracted a debilitating cold, complete with sore throat, cough, and other symptoms.

“My strength is prostrated beyond anything that I ever experienced before,” he moaned. It was, after all, his first “campaign.” He had refused to campaign in 1824 and 1828 when he ran for the presidency, and now that he was not even contemplating that office, he finally learned what campaigning was likeâand he rather enjoyed it.

After President Tyler declined to run for a second term, former Speaker James K. Polk of Tennessee won the Democratic nomination for President in 1844 and the presidency itself, defeating the perennially ambitious Henry Clay. As loser, Clay nonetheless shared one distinction with his winning opponent: news of the presidential election results had, for the first time in history, traveled over the wires of a new invention, the telegraph.

During his last month in office, President Tyler asked Congress again to approve annexation of Texas, and although John Quincy had blocked

two earlier attempts, the House finally approved it in February 1846. As John Quincy had predicted, war with Mexico followed Polk's assumption of power. Only ten members of the House joined John Quincy in voting against the war.

two earlier attempts, the House finally approved it in February 1846. As John Quincy had predicted, war with Mexico followed Polk's assumption of power. Only ten members of the House joined John Quincy in voting against the war.

In November 1846, John Quincy suffered a stroke while visiting his son Charles Francis in Boston. Rendered speechless and confused, his right side paralyzed, he seemed close to death; his doctors gave Louisa little hope for her husband's recovery. As she kept vigil in his room each day, however, he gradually recovered his speech, then his mind and memory, and by early December, he laughed off his illness, snapping at his friends that he had suffered only vertigo. But when he tried to stand and walk, he fell; he could no longer support himself.

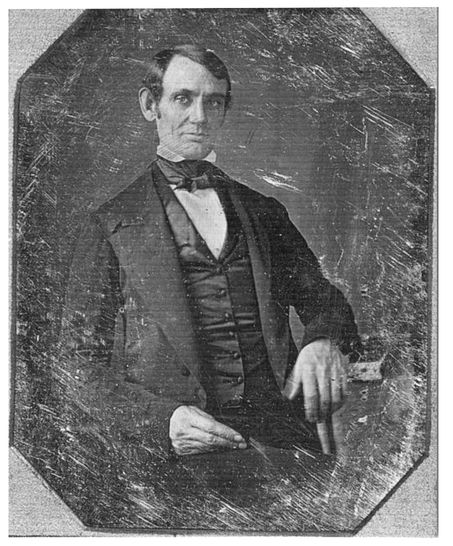

By Christmas, however, he was talking about returning to Congress, and on New Year's Day, he set out for a ride in his carriage. A month later, on Sunday, February 7, sheer willpower held him upright as he walked from his son's house to both morning and afternoon church services to take communion. Despite protests from his wife and son, he and they, and a nurse, left for Washington the next day, reaching the Adamses' F Street home in February 1847, in time to celebrate Louisa's seventy-second birthday. The following morning he walked slowly, but magisterially, onto the floor of the House, and as he took his seat, the members rose as oneâNorth, South, East, and Westâto cheer him. Among those celebrating his return was a tall, lanky, unkempt freshman congressman from Springfield, IllinoisâAbraham Lincoln. During his short tenure in the House, Lincoln would prove one of John Quincy's strongest supportersânot just in the cause of abolition but regarding Adams's proposals for federal initiatives in highway and canal construction and other forms of national expansion. Echoing the words of James Monroe and John Quincy Adams, Lincoln asserted that “Congress has a constitutional authority . . . to apply the power to regulate commerce . . . to make improvements.”

36

36

After Congress recessed in 1847, John Quincy insisted on returning to Quincy for the summer. Friends and relatives staged a gala eightieth birthday party for him on July 11, and two weeks later, they feted John Quincy

and Louisa's golden wedding anniversary. John Quincy overwhelmed Louisa by giving her a beautiful bracelet that his son Charles Francis had purchased for him.

and Louisa's golden wedding anniversary. John Quincy overwhelmed Louisa by giving her a beautiful bracelet that his son Charles Francis had purchased for him.

Â

Congressman Abraham Lincoln won election to the House of Representatives in 1847 and served during John Quincy Adams's last days in Congress. He is seen here in a daguerreotype probably taken in Springfield, Illinois, in 1847.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

On November 1, Louisa and Charles Francis took John Quincy back to Washington, but the trip exhausted himâleft him palsied, his entire body shaking. Too weak to speak audibly or to write, he walked unsteadily; he was nearly blind. He nonetheless insisted on taking his seat at the opening of the House on December 6, and Louisa conceded, “The House is his only remedy.”

37

37

Although he gave up all but one of his committee obligations and rode instead of walking to the House, he appeared for every roll call every day

thereafter. He cast one of only four votes in favor of a resolution to withdraw U.S. troops from Mexico. Even Lincoln voted against it. And his face, if not his body, came to life when he heard a resolution supporting a Spanish government demand that the United States pay the

Amistad

's owners $50,000 for the loss of their ship and its “cargo,” which the Spanish minister characterized as a band of assassins. Although he lacked the spring that once shot him to his feet, he nonetheless accomplished the same result and assailed the Spanish minister for having wanted the

Amistad

captives “tried and executed for liberating themselves.”

thereafter. He cast one of only four votes in favor of a resolution to withdraw U.S. troops from Mexico. Even Lincoln voted against it. And his face, if not his body, came to life when he heard a resolution supporting a Spanish government demand that the United States pay the

Amistad

's owners $50,000 for the loss of their ship and its “cargo,” which the Spanish minister characterized as a band of assassins. Although he lacked the spring that once shot him to his feet, he nonetheless accomplished the same result and assailed the Spanish minister for having wanted the

Amistad

captives “tried and executed for liberating themselves.”

“There is not even the shadow of a pretense for the Spanish demand,” John Quincy growled after the laughter subsided. “The demand, if successful, would be a perfect robbery committed on the people of the United States. Neither these slave dealers, nor the Spanish government on their behalf, has any claim to this money whatever.”

38

The House agreed and rejected the proposal. He then presented two petitions for peace with Mexico, and the House rejected them both.

38

The House agreed and rejected the proposal. He then presented two petitions for peace with Mexico, and the House rejected them both.

By mid-December, he had grown too weak to continue writing in the diary he had kept for sixty-eight years, and, indeed, he had to refuse a treasured invitation to speak at the laying of the cornerstone of the Washington Monument on December 10.

On New Year's Day, he wrote to his only surviving son, Charles Francis, and, with an unsteady hand, wished him “a stout heart and a clear conscience, and never despair.”

39

On February 21, 1848, President Polk sent the Senate a treaty of peace with Mexico for ratification. In the House, supporters of the war proposed sending the thanks of Congress to the American generals for their victory. When the echoes from the roar of “ayes” had faded, a single, shrill voice startled the Congress. In a last, desperate effort to punish those engaged in what he called that “most unrighteous war,”

40

John Quincy Adams sounded a firm, unmistakable “No!” It was his last word to the Congress he cherished.

39

On February 21, 1848, President Polk sent the Senate a treaty of peace with Mexico for ratification. In the House, supporters of the war proposed sending the thanks of Congress to the American generals for their victory. When the echoes from the roar of “ayes” had faded, a single, shrill voice startled the Congress. In a last, desperate effort to punish those engaged in what he called that “most unrighteous war,”

40

John Quincy Adams sounded a firm, unmistakable “No!” It was his last word to the Congress he cherished.

Other books

Beautiful Mine (Beautiful Rivers #1) by J.L. White

The Easy Day Was Yesterday by Paul Jordan

Hens and Chickens by Jennifer Wixson

Riding the Bus With My Sister: A True Life Journey by Rachel Simon

The Last Letter by Kathleen Shoop

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin

Surfing the Gnarl by Rudy Rucker

Waiting for Love by Marie Force

Anita Blake 23 - Jason by Laurell K. Hamilton

The Concert Pianist by Conrad Williams