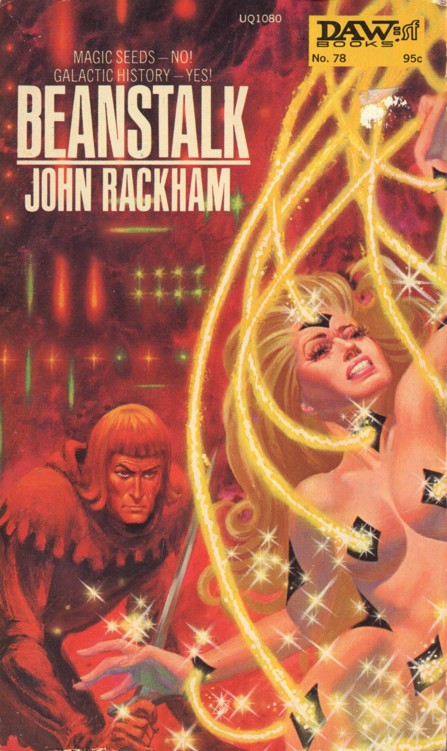

John Rackham

Authors: Beanstalk

UP

AND

AWAY!

UP

UP,

First

there was the little man from the sky. Then there was the planting of the

seeds. The towering structure came overnight— never had anyone seen a taller—and

it had grown to the very sky.

Then

they climbed the tower

...

And there was the place no one had ever

seen

before.

It was the place with the huge structures,

the place with the singer in the cage, the place with the booming voices.

And

the giant.

Yes, the giant.

They were all called by other names—the

little man explained it all.

But to Jack, the son of the Widow Fairfax, it still smacked of magic.

But, witchcraft or not, there was work to be

done and a war to fight. Courage, in any case, is not linked to understanding.

Fortunately—for a thousand planets.

Beanstalk

by

John

Rackham

DAW

BOOKS

,

INC.

donald a.

wollheim,

publisher

1301

Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y.

10019

C

opyright

©,

1973,

by John

R

ackham

All Rights Reserved. Cover

art by Kelly Freas.

FIRST

PRINTING,

NOVEMBER

1973

123456789

BMP*

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

Jack lay flat on the greensward at the foot

of the old grandfather oak. One outflung gnarled branch kept the sun from his

face but gave him loopholes through which he could stare up at the deep blue of

the cloudless afternoon sky. He lay still, and stared, but he saw only his

thoughts, and they were far from pleasant. The many sounds of the forest

blended into a peaceful and familiar murmur in his ears, but failed to find an

echoing peace in his mind. Although the small holding that kept him and his

widowed mother was but a few acres, there were chores in plenty to keep him

busy, and a moment such as this, with his lunch of black bread and sour ale

eaten, and Brownie the milch cow a few score yards away placidly cropping, leaving

him time to think

...

such a moment

was rare, and he needed it. No matter how he thought of it, the future looked

dark and depressing.

At

nineteen, Jack considered himself a man full-grown, and his six foot and more

of well-muscled frame supported his opinion, but the burden he had to bear was

such as would have bowed a man with twice his years and experience. In reach

of his left hand lay a pewter tankard that he had won only a year ago for his

skill with the longbow, which lay equally close to his other side. For that

achievement, and because he had the favor of Earl Dudley's eye

...

in fact it was commonly accepted that

there was a blood kin between Dudley and himself, because of the traditional

privilege of jus primae noctis that the Earl had claimed on Edwina, Jack's

mother

...

for that and other

reasons, Jack Earl Fairfax should have gone with Dudley's men, overseas and to

the Holy Land, to fight the infidel Saracen. The Crusades, a word to fire the

adventurous blood of a young man of spirit itching to break out of the

narrow

confines of a small village life, and how he had looked for it, worked toward

it. But a malicious fate had decreed otherwise. Only eight months since, on a

blowy, blustery autumn morning, Freeman Will Fairfax, small holder and warden

of the Royal Deer in those parts, had set out on his gray-dawn rounds. And a

treacherous elm had shed a stout branch, as elms are apt to do, especially

after a thunderstorm, without any warning. No man can take care

all

the time. Freeman Fairfax had died instantly, an instant that stole

Jack's dreams and hopes and promoted him to a heavy responsibility.

But

it hadn't ended at that. With an office to fill and his mother to keep, Jack

saw his crusading dreams disappear, and felt cheated as he helped to lay his

father to rest. Then the old sow, well serviced by Freeman Dennison's

blood-boar, died unexpectedly and unaccountably in farrow. Widow Fairfax, wise

in husbandry, had slaughtered all the Utter but one, knowing well that it would

be impossible to rear more than one by hand. Little of that meat remained, and

the piglet had thrived poorly for all their care. In the first crack of spring

three of their four cows managed somehow to find and eat some weed that poisoned

them, leaving only Brownie. The acre of oats looked thin and poor. The

cabbages, kale, and potatoes were showing promise, but everything else seemed

to have caught the general evil. And tithes were due in a matter of weeks. In

other years it had always been possible, somehow, to save and sell at market a

good cheese or two, a young pig, even a little good oat grain, and thereby get

enough silver to pay tithe and have something left for salt, and yeast, and a

length or two of good cloth.

But this year . . . ?

Whichever way Jack chewed it in his mind's

teeth he had to come back to his mother's words.

"We

will sell Brownie to pay tithe. At least we will escape debt!"

But

then, Jack demanded silently of the indifferent forest, what shall we do then?

He knew there was no answer. Muttering softly in helpless anger he said,

"Even were my Earl of Dudley himself here he could do little. All know

that he is a strict man with silver, though kindhearted enough in other things.

And he is not here, nor will be for many a long month!"

Which

was true.

Dudley had gathered his men and departed with the first fine weather,

bound for foreign lands and the infidel foe, leaving in his stead Bernard the

Seneschal, a dour old graybeard who knew nothing better than to keep the strict

letter of the law in his lord's absence. No charity could be expected there.

Nor hope anywhere else. Jack looked at it again and again, feeling rising anger

and futility. It was all wrong, all unfair, and yet there was nothing he could

do about it.

He

stirred, roused restlessly to an elbow, and Brownie, on the far side of the

glade, lifted her placid head a moment to stare at him,

then

went back to her feeding.

We'll not starve,

he thought,

not

while there's deer that no one will miss!

That was

a

desperate crime that he had opened his mind to long ago. But it was a

stopgap only. It would solve nothing to poach the very deer he was in honor

bound to protect. For a moment or two his thoughts ran fancifully to visions of

strange benefactors:

a

wandering stranger with a deep purse perhaps;

or a hobgoblin? Old men's tales had it that the little men of the woods knew

where gold and precious gems were hid, if you could make them talk. There was

even a fanciful tale of a man, northward in another part of the forest, who

commanded a wild band of outlaws to rob the rich and help those who were poor.

Robin of the Greenwood, so they said.

And there was that

hunched old crone who lived all alone, away the other side of Castle Dudley and

who was

a

witch,

so it was said. But Jack had to grin wryly at the run of his imagination and

pull his mind back from such things. Magic was for the credulous. What he badly

needed was something practical. What his mother needed sorely was a strong man

about the place to keep and comfort her. In the scant months since his

father's death he had seen her grow visibly old and inturned, her golden hair

now as dull as her eyes, her voice heard seldom above a whisper, yielding to

the defeat that faced them. Once she had been fair, shapely,

lovely

enough to catch the eye of Earl Dudley himself.

But now . . .

?

"It's

all wrong!" Jack said it aloud, violently, hopelessly, and Brownie flicked

an ear, turned her placid brown eyes on him as he clambered to

bis

feet and gathered up his satchel, threading the tankard

on the strap. Then he took his bow, nearly six feet of good stout churchyard

yew, and the quiver of goose-quilled cloth yards, two dozen of them, and slung

them angrily across his broad shoulder. What good were they now?

Far away and high overhead a small strange

noise puzzled his ear. As he craned his head to look up that noise grew

enormously, shook the whole sunlit world, plunged needle-tipped hurt into his

ears,

shivered

the whole of his body so that he threw

himself face-flat in terror, wrapping his arms about his head. Was it Beelzebub

himself descending in wrath? Would the Lord of this World

come

this close to high noon, and from above? The impossible noise grew sideways,

not louder but somehow

more dense

and solid,

substantial enough to shake him as the hammer of a thunderclap shakes the solid

ground. Coherent thoughts deserted his mind and he prepared to die. It could

only be the Day of Judgment itself, in such ravening fury. Benumbed, he felt

the solid world under him leap in shock, and subside again. Then, shockingly,

the vast uproar stopped and there was a deafened silence through which small

sounds found their way like ants through a crack in a wall. As bells rang

sourly in his head, Jack waited, drew a careful breath, let it out again, and

dared to lift his head a fraction, to peer. Chill fingers danced lightly along his

backbone at the sight.

There

in the glade, between himself and Brownie, hung an evil blue cloud like a

smoke-puff with a shape of its own, so clear and pale that he could see

Brownie's stricken carcass through it, yet so terribly real that he never for a

moment doubted its existence. His nostrils twitched anticipating brimstone.

This had to be hell-fire, for certain. He stared in fearful fascination, and

saw the blue grow rapidly darker and more solid, writhing with inner torment,

gathering in on itself, darker and darker until it was a black that seemed to

draw the eyes from his head for a breath or two. Then, in a blink, it was gone

as if fallen into its own creation. There in its place some equally fearful

but utterly different marvel stood, defying his puzzled eyes.

There

were many rods, a great number, each no thicker than a willow-wand but of some

strange silver-glitter stuff, and so shaped and joined together as to enclose a

space like a big ball but with flat facets. And the flat facets had

a sheen

on them too, like the surface of a pond when the

wind holds still. The whole baffled bis peasant's mind to comprehend. It was

some kind of basket, perhaps, but of such a size and quality as he had never

imagined. And now he saw, through those shimmering facets, that there were

fires within, small points of flame that glittered and winked in many colors,

in green and red and yellow. And something moved in there, a dark shape that

aroused new fears in his mind. Was this thing some fiendish chariot?

That

...

thing

...

inside seemed dark and sluggish and

small.

He felt that it moved close to

a flatness

and peered at

him

malevolently, so that he ducked down quickly. Shaking all over, he

gathered his intentions and muscles, clutched his bow and quiver, braced

himself

, then sprang up and leaped for the shelter of the

great oak's trunk. Once behind it he shook his bow into his hand, plucked an

arrow and nocked it, drew far to his chin and then eased himself daringly

around the trunk, ready to loose at anything that might offer itself.

The

impossible structure still stood, but now its shape had altered a little. It

had grown a limb at one side, a projection that stretched out and down to the

green turf. It was

,

it had to be, a ladder or gangway

of some sort. That thing in there was setting ready to come out. He spread his

feet more, set his shoulder solidly against the oak, and held ready to spit the

thing, whatever it was, devil or not

Past

his

shaft-point he saw movement. Here it came now, a small, hunched, horrible,

helmeted creature, no more than four and a half feet tall. He got it perfectly

in his sight, froze, held his breath, loosed the shaft, and followed it with

anxious eye as his hand by itself found another arrow and set it ready.

The

shaft flew true, and he had known it would. But then his jaw fell as he saw it,

on the point of piercing that horrible creature somewhere between neck and

chest, suddenly leap aside with a crack as if it had struck metal, to plunge

and quiver in the turf some ten feet clear. Armor! Of course he had expected

the foul fiend to be girded in some way against attack, but what devilish kind

of armor was it that a man couldn't see, yet could turn a cloth yard steel tip

at this range? Curiously, the impossible served to cast doubt into Jack's mind.

Would the Evil One be armored in such fashion? Would it not be more likely

that a man who dared to loose a shaft against him would be struck dead

immediately? Chewing on his conflicting thoughts, Jack drew his second shaft

tight to his chin and stood clear, daringly.

"Hold

there!" he shouted boldly. "Hold there, whatever you may be, or

I’ ll

try that armor of yours again!"

The

words echoed in the glade. The squat dark creature turned, seemingly with great

effort. Jack saw a dark, hook-nosed visage and oddly bright eyes. Then a

curiously quiet voice whispered, inside his head.

"Friend.

I mean you no harm. I ask your help. Help me. Help

..."

That strange "voice,"

quiet to start with, seemed to fade away altogether. Jack felt a ghost-pain,

a

sudden grip at his stomach that came and

went in

a

breath.

Then the strange being tottered and fell, facedown in the grass, and lay still.

Suspiciously, Jack waited a long while before moving,

then

he moved forward one nervous step after the other, bow half-drawn and ready,

his eyes alternating from the inert fiend to his devilish chariot. Fires still

winked and blinked their varicolored mystery inside that strange structure. He

saw now that the curious facetings were eight-sided and filled with some

tight-drawn kind of skin that he could see through. The downstretched gangway

was of the same kind of stuff. It didn't appear substantial enough to walk on.

And now, closer still, he felt a ghostly touch and tingle that made his skin

cringe and lifted his hair in bumps along his forearm as it braced the bow. A

powerful

spell

, undoubtedly.

But what of the enchanter himself?

The small creature was manlike in a

grotesque way, not black as Jack had first assumed but a deep dark brown like

well-worn walnut, with

a

barrel chest and sinewy arms that hinted at

great power and energy. The helmet was a curious device, unlike any armor Jack

had ever seen. As round and smooth as a half apple, it had two spiked growths

like horns, but of polished copper, and the whole was secured in place by a

chin-strap that was decorated with curious bumps and knobs. For the rest the

creature had no armor at all that anyone could see, only

a

complicated web-work of glossy stuff that was associated with a broad

belt of the same substance. And that belt had its share of lumps and bumps, and

hooks that held pouches and boxes. It was all in all a most baffling beast, but

Jack saw and envied one thing, the beautifully polished calf boots the thing

wore.

His own

rough hand-sewn sandals were nothing by

comparison. By the movement of slow breathing he could see that the creature

still lived. If those boots had only been bigger

...

and would that walnut-hued hide turn another shaft,

this

close? He debated it inwardly, gripping his bow.

What

had the creature said, in that magical manner?

Friend?

Meaning no harm? How could that be? If this thing was some kind of goblin—and

he had decided to start believing in goblins a few moments earlier—then it was

an enemy and threat by definition. What was more, if there were after all such

things as goblins, then perhaps that other tale, about pots of gold,

was

also true. Jack

retreated

a

cautious pace and turned so as to be able to keep the weird chariot in view.

Then he saw Brownie shudder, lift her head, and then lumber to her feet, apparently

none the worse. He clicked his tongue, called soothingly to her, and she

tossed her head a time or two,

then

started once more

to graze.