Languages In the World (10 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

The significant point to make here is that reconstructive practices take languages out of their contexts in order to compare and contrast their vocabularies and grammars with those of other related languages. The practice is fairly straightforward. Romance philologists, for instance, line up words on a page and try to construct the original

phonetic material that the present-day words came from. Here is an example of a set of cognates meaning ânight':

| Italian | French | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

| notte | nuit | noche | noite | noapte |

| [nÉttÇ] | [nyi] | [noʧe] | [noitÇ] | [noaptÇ] |

Through establishing the regular sound changes that occurred as Latin and then Vulgar Latin developed into the various daughter languages, philologists reconstruct Latin

*

noctem

. They try again with a set of cognates meaning âeight':

| Italian | French | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

| otto | huit | ocho | oito | opt |

| [ÉttÉ] | [yit] | [oʧo] | [oitÉ] | [opt] |

They are encouraged to reconstruct Latin

*

octem

.

Sure enough,

noctem

and

octem

can be found in Latin manuscripts; they are therefore attested, and the asterisk is removed. Across a long list of cognates, the Latin medial consonant cluster -ct- can be seen regularly to turn into a geminate (double) consonant in Italian, be lost entirely in French, and become palatalized in Spanish, unclustered in Portuguese, and dissimilated in Romanian. The phonetic processes of gemination (Italian), palatalization (Spanish), and dissimilation (Romanian), as well as full (French) or partial (Portuguese) consonant loss, are likely the very same ones that affect other consonant clusters in the respective languages as they evolved. In all cases, modern French is the language the most phonetically distant from Latin, since it lost many final vowels and consonants. Its spelling is conservative, however, and in many cases retains final segments no longer pronounced, as in the word

nuit

ânight,' which is written with a final -t# but pronounced without it. The structural details of the development of Latin into the Romance languages will be taken up in Chapter 8. A more in-depth look at language change is the topic of Chapter 11.

The process of decontextualizing languages so that they may be compared and contrasted has led to four principal ways to classify languages.

A genetic classification is necessarily historical, and the story of these languages is one of divergence over time and space. The hypothesis is that families of languages classed in a stock descend from a common source, known as the protolanguage. All protolanguages are prehistoric, and there are no documents written in those languages. The people speaking the protolanguage are thought to have lived together for an extended period of time, perhaps even thousands of years, and then at some point they start to spread out and move away from one another, with different groups going in different directions. The movement of people and time are major organizing themes in this book, and we will be taking them up in Parts III and IV, respectively.

In the past several hundred years and more, philologists have worked out the general language stocks of the world. In some cases, the evidence is equivocal and leads to disagreements, such as the case of the classification for Korean and Japanese. In some cases, disagreements about where to divide between stocks are due more to cognitive taste, depending on whether one is a so-called lumper or a so-called splitter. In this book, we:

- accept for Africa, Eurasia, and parts of Oceania a classification of 13 different language stocks, with their major branches; we accept perhaps seven phyla, three of which cover the languages of Australia (Aboriginal Australian), New Guinea (Indo-Pacific), and an old lineage in Africa (Khoisan); these are listed in the front matter of this book;

- recognize that North and South America have dozens of language stocks;

- acknowledge the possibility that some stocks and phyla may be areal classifications, sometimes called

wastebaskets

rather than genetic classifications; and - want to acknowledge furthermore that genetic classifications for the world's sign languages do not yet exist.

Sign languages do not all derive from one source, and their lineages do not necessarily line up with the spoken languages around them. The language family for ASL, for instance, includes French, because ASL is a combination of Martha's Vineyard Sign and French Sign. It is not historically related to British Sign Language. There are over 130 documented sign languages in the world, and certainly others undocumented, in addition to countless so-called village sign languages, developed away from urban centers, and even idiosyncratic forms of home signs that arise in the context of individual families who are not connected to larger deaf communities.

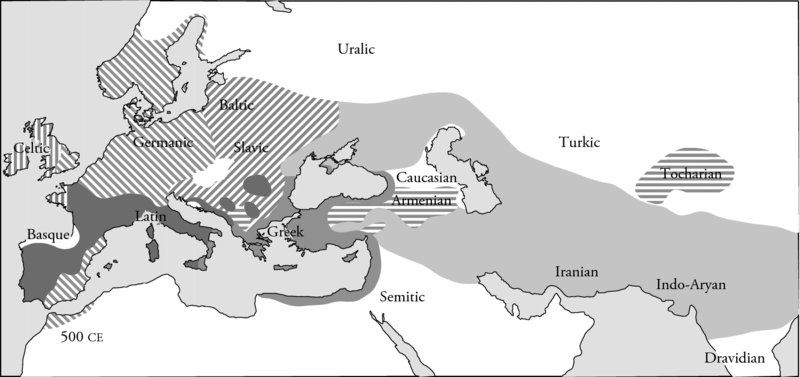

The oldest reconstructable language stock is Caucasian whose time-depth goes back to 8 kya. The Indo-European stock (see

Map 3.1

) is reconstructable to 6 kya, meaning

that it has taken that many years to produce languages as different as Hindi and Welsh, Polish and Tajik. For the sake of consistency in dating stocks and families, time-depth is determined by the time of the hypothesized break-up of the population of speakers. Because human language as we know it may well be 150,000 years old, there is an enormous time gap between those beginnings and the glimpse we get of language from their relatively modern reconstructions. We take up the challenge of filling that gap in Chapter 10.

Map 3.1

Early distribution of the Indo-European linguistic groups. “IE1500BP.” Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons (

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: IE1500BP.png#mediaviewer/File:IE1500BP.png

).

An areal classification is by definition geographic, and the story of these languages is one of convergence in time and space. Whereas genetic classifications are based on hypothesized reconstructions of languages long dead, areal classifications arise from known circumstances and give linguists rich understandings of the kinds of context-induced changes that can happen when speakers from different languages inhabit a defined geographic area for a long period of time.

Many linguistic areas exist around the globe. One is mainland Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, parts of northeast India, and southern and southwestern China) where languages from three different language stocks have been in contact for millennia, namely Austric, Hmong-Mien, and Sino-Tibetan. Another is South Asia, where centuries of contact between Indo-European (Urdu, Marathi) and Dravidian (Kannad'a) languages have induced structural and semantic similarities, even without many borrowed words. The Americas provide any number of examples, the Vaupés River Basin in Brazil and Columbia being but one, where unrelated Native American languages have converged on certain phonetic and grammatical features in a way unique to that region. Mesoamerica is another.

Some linguists argue that Africa is a convergence zone all its own, because, among other things, some unusual phonetic features are found only in African languages. However, even within Africa, there are further convergence zones, such as the Kalahari Basin in southern Africa, where speakers of Khoisan languages and at least one Bantu language have been in contact for an extended period of time. Some linguists have suggested Europe as a convergence zone. In the 1930s, linguistic anthropologist, Benjamin Lee Whorf, proposed a notion of Standard Average European to capture broad grammatical similarities shared by the languages spoken in Western Europe. He focused in particular on the ways speakers of these languages conceive of time as a smooth-flowing continuum and how they express this conception by means of past, present, and future tenses. Not all languages organize their temporal distinctions this way.

The kinds of influences found in areal classifications include:

As was noted in Chapter 1, lexical items get traded rather easily when speakers and their languages are in contact. It is not uncommon for phonemes to be traded, as well. Take the high front round vowel [y]: there is a continuous area of Europe where [y] is

found, beginning in France and extending up along the northern coast of Europe including not only Belgium, the Netherlands, northern Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, whose citizens speak an Indo-European language, but also Finland, where Finnish is a Uralic language. Now notice that French has this sound, whereas the other Romances languages, namely, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian, do not. German has this sound, whereas English does not, though both are West Germanic languages. We know in the case of English that Old English had this sound but later lost it, so the [y] in German may well be an inheritance from Common Germanic. However, the presence of the sound in French cannot be explained by the history of the Romance languages. Only geographical proximity to speakers who do have this vowel can explain it.

Another strong areal feature involving sound can be found in Asia. Many of the languages of East Asia â Lao, Thai, Vietnamese, all varieties of Chinese, and some varieties of Tibetan â are

tone languages

. In tone languages, word meaning is distinguished by the pitch or âtone' put on individual words. The kind of tones found in languages in Asia tend to be

contour tones

. To pronounce individual words the voice may rise, fall, fallârise, stay flat, break in the middle of a word, or make some other kind of gliding movement. In Vietnamese, the following words are in contrast:

| giáy | già y | giay |

| rising tone | falling tone | flat tone |

| âpaper' | âshoe' | âsecond' (as part of a minute) |

If you say the syllable

giay

as if you were asking a question (in English), you are saying âpaper.' If you say the syllable as if it were at the end of a sentence (in English), you are saying âshoe.' If you say the syllable with no fluctuation of your voice, you are saying âsecond.' Change the tone, and you change the meaning of the word. The number of tones varies in number from language to language. Mandarin has four. Thai has five. Vietnamese has six. Cantonese has nine or 12, depending on how one counts. Burmese, Japanese, and Korean have a simpler tone system, often called

register

or

pitch

, where the tones can be described in terms of points within a pitch range. Register tone languages are found widely in Africa. To round out the picture in Asia, some languages have no tone: Malay (Austronesian), Khmer (Austroasiatic), and the Philippine languages Tagalog and Ilocano.

English and Indo-European languages in general are

intonation languages

. English speakers, for instance, change the contour of whole sentences in order to make a statement a question, for instance, or to emphasize what is most important. Note the difference in the tone you use when saying: “This is

really

interesting!” as opposed to saying, in astonishment: “

Really

?” You are not changing the meaning of the word; you are indicating a different emotional relationship to it. Although Indo-European languages in general, and the Germanic languages in particular, are not known for having tone, it is the case that Norwegian and Swedish, two North Germanic languages, are classed as tone languages and have a binary tone contrast.

What is amazing to consider for our current discussion is the fact that Vietnamese began as a nontone language, though under the influence of the surrounding languages, it has acquired contour tone. The presence of tone in Vietnamese is not a

genetic feature inherited from Proto-Austroasiatic, its source language, but rather an areal feature, acquired through sustained contact over time with tonal languages.

Grammatical constructions can also spread across an area. The term

Sprachbund

âlanguage league' was originally coined to capture the linguistic situation in the Balkans. Here, a variety of languages â all Indo-European, but from different branches â have met and mingled for centuries: Romanian (Romance), Albanian (Albanian), Greek (Hellenic), Roma (Indo-Iranian),

7

and the South Slavic languages Bulgarian, Croatian, Macedonian, and Serbian. In some cases, the varieties of Turkish, a Turkic language, spoken in the Balkans as well as Hungarian, a Uralic language, show Balkan features. Certainly, there are many Slavic and Hungarian words in Romanian and, conversely, many Romance words in the South Slavic languages, as well as Turkish words in Romanian and South Slavic.

8

Of note is the fact that the word

balkan

is the Turkish word for âmountain.'

More to the point, and to repeat what was said about Spanglish, mixing languages means more than sprinklings of lexical borrowings. Rather, the mixing occurs on fundamental structural levels. In the languages of the Balkans, there has been a remarkable convergence of grammatical features. We mention only four here and exemplify them by Romanian:

- All have replaced the infinitive with an analytic subjunctive. Instead of saying âI want to go,' the preferred pattern is

vreau sÄ merg

, âI want that I go,' where

sÄ

is the conjunction âthat'; the verb endings show the person, meaning that personal pronouns are not always necessary. - Bulgarian, Macedonian, Romanian, and Albanian have postposed definite articles. Instead of saying âthe boulevard,' which is the preferred pattern in Greek, they say

bulevardul

, âboulevard the,' where

-ul

is the definite singular article for masculine and neuter nouns.

9 - They make use of resumptive

clitic

pronouns of the type

am vÄzut-

o

pe Maria

, âI saw/have seen-her Mary,' that is, âI saw Mary' where the pronoun

-o

is cliticized to the past participle of the verb âto see,' and the preposition

pe

picks Mary out. - They mark the future with a verb or participle from the verb âto want' rather than âto be' and/or âto have,' which is common in other Western Indo-European languages; so the

vom

of

vom vedea

âwe'll see' is etymologically related to

vrem

âwe want.'

These grammatical convergences are evidence of multilingualism existing in this area for centuries and perhaps even millennia.

Affecting areal classifications are several sociolinguistic factors. One of these â prestige â travels well across linguistic and cultural borders, and relative prestige

indexes who the lenders are and who the borrowers. We, the authors, have an expression: Chinese is the Arabic of the East, Arabic is the Greek of the Middle, and Greek is the Chinese of the West. That is to say that Chinese (Mandarin), Arabic, and Greek (plus Latin) have had enormous influence on the languages and cultures in their respective regions, which we will be seeing throughout this book. Prestige creates asymmetric effects of one language on another.

The plain root

*

b

h

er-

illustrates the story for the West. It comes into English, as mentioned above, in the word

bear

as in âto bear a child' or âto bear a burden.' It is recognizable in the word for âchild' in Scottish

bairn

and Danish

barn

. Reflexes of this root have come into English by way of the plentiful Latin words borrowed mostly through French with the root

-fer

, as in

confer

,

defer

,

infer

,

prefer

,

refer

,

transfer

, and so forth. We should count those with

-late

, as well, because the verb âto carry' in Latin is suppletive, which means that its subparts do not match, and its subparts are:

fero

(present tense)

tuli

(past tense)

latus

(past participle).

10

The past participle gives us further borrowings of the type

relate

and

translate

. Finally, there are the Greeks with their root

phor-

/

pher-

, which have given English words such as

metaphor

and

paraphernalia

, the latter literally âthat which you carry around with you.' Now note that

transfer

,

translate

, and

metaphor

(meta = trans) are translations of one another. The point is that the Western European Indo-European languages have acted as a kind of recycling mill for Indo-European roots for the last 2000 years, with Greek and Latin supplying most of the grist.

A second sociolinguistic factor affecting languages in contact concerns speakers' attitudes and cultural norms. We got a glimpse of speakers' attitudes already at the end of Chapter 1 with respect to English and Spanish. All over the world, some groups are more open, and some groups less open, to borrowings and contact-induced changes. If two groups are in economic or political conflict, they are less likely to be open to linguistic tradeoffs. There may even be cultural prescriptions, for instance, against lexical borrowings, such as in the Vaupés area in the Amazon, mentioned earlier, although this restriction did not stop grammatical restructuring. In North America, differing cultural attitudes among the Iroquoian languages resulted in different impacts from the encounter with French and English. The conservative Ononadaga resisted linguistic change due to contact, while the Mohawk, with a different attitude toward outsiders, accepted it (Mithun 1992).