Languages In the World (13 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

Effects of Power

Power is often associated with money and muscle. Indeed, power and money do attract one another, and there is no doubt that the richer you are and the bigger and stronger you are, the more often you get your way. However, in matters of language, power has qualities more like wind or water or

chi

in that it is ever present and relentless, and circulates in the spaces, both large and small, where it can. We begin our examination of the macrodynamics of the language loop through the prism of power in Part II by noting that:

- Power is bound to freedom and flows through fields of possibilities. Although actions taken by individuals are not predetermined, they are nevertheless always bound by the constraints of a given time and a given place. The rebellious teen who freely chooses to go Goth has, first of all, not invented the category

Goth

and must, second of all, live with the consequences of this identity choice. When, in the twentieth century, ethnic Croats decided to become independent, they did not imagine their liberation in terms of a feudal state, a city-state, or a monarchy; they wanted a nation-state, just like all their neighbors had. Turning to the relationship between language and the nation-state, as we will do in Chapter 4, it was a necessary part of the Croats' independence that Croatian would be understood to be a separate and distinct language from Serbian. - Power is productive; it brings states of affairs into existence. Once the contingencies of science and politics have created the category

insane

, the nation-state can produce and then mobilize an apparatus affecting the behavior of those identified as insane. Similarly, once the contingencies of science and politics have produced the domain of sexuality as a field of knowing, then certain identities come into being: homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, asexual, and so forth.

These identities then organize the social worlds of those hailed into those categories and can determine, for instance, the legal rights pertaining to whether two people can be married. In Chapter 5, we will trace how the domain of writing came into existence and then explore the consequences of this invention. The power of the written word is well known, and those who know how to read and write are able to produce such things as sacred texts, Declarations of Independence, laws, writs, literature, blogs, op-ed pieces, and textbooks (the list is endless), which represent the beliefs/demands/rights/views of those who have access to this kind of power. - Power is not held absolutely; it is diffused. This is to say that one need not be in the position of power in order to exert power. A female phone sex worker, fulfilling the fantasies of men she would find offensive and subjugating in her private life, makes more money the longer she can draw out her clients' fantasies. A prisoner may go on a hunger strike as a way to assert control over his life and actions. When it comes to matters of language, as we will see in Chapter 6, power plays are found everywhere and often lead to violence. However, as long as one has a voice, one can use it, if one dares. In 2010, Cantonese speakers took to the streets of Guangzhou (historically, Canton) to protest a local politician's proposal that a local television station stop broadcasting in Cantonese and replace it with Mandarin.

We humans are far enough down our sociohistorical language road to have produced well-defined institutions â religious, economic, political, legal, educational â through which power moves and by which systems of differentiation are created. In the eighteenth century, grammarians wrote their prescriptive rules in order to distinguish between those who knew how to speak correctly and those who did not, with the former enjoying privilege and prestige and all the benefits that come with position. Several centuries earlier, Africans had been captured and taken as slaves to both North and South America. In the United States, the conditions under which these people lost their African languages and adopted English produced a variety known today as African-American English, which is often stigmatized, just as its speakers sometimes are.

In the chapters that follow, we are concerned with putting under global review the ways speakers and their languages are advantaged and disadvantaged by the effects of power, for example, whether their language is seen as a national language or is deemed a dialect, whether their historical records are preserved in libraries or are set in flames, and whether their language is declared official or is banned.

Effects of the Nation-State and the Possibility of Kurdistan

In 1915 and 1916, while World War I was ravaging Europe, an English diplomat, Sir Mark Sykes, and his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, met in a series of negotiations. The result of these meetings was the SykesâPicot agreement that would determine the zones of influence in the Middle East for Britain and France. Arab cities such as Baghdad (present-day Iraq) and Kuwait City (present-day Kuwait) were placed under British rule, while Beirut (present-day Lebanon) and Damascus (present-day Syria) fell under French rule. Their negotiations seem to have been an exercise in cartographic whim. Sykes is reported to have said, “I should like to draw a line from the

e

in Acre to the last

k

in Kirkuk.”

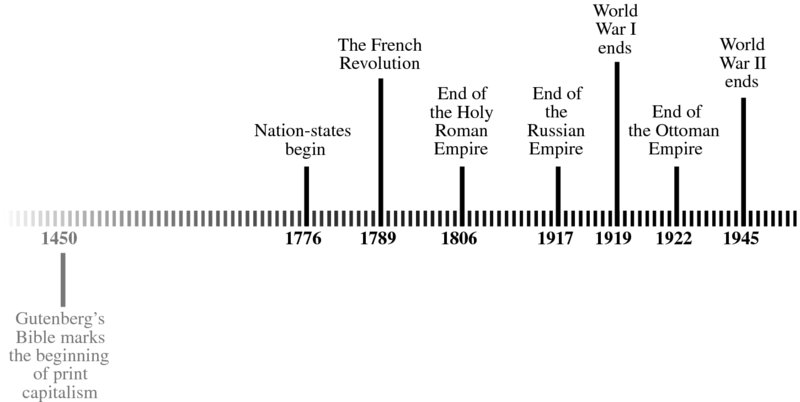

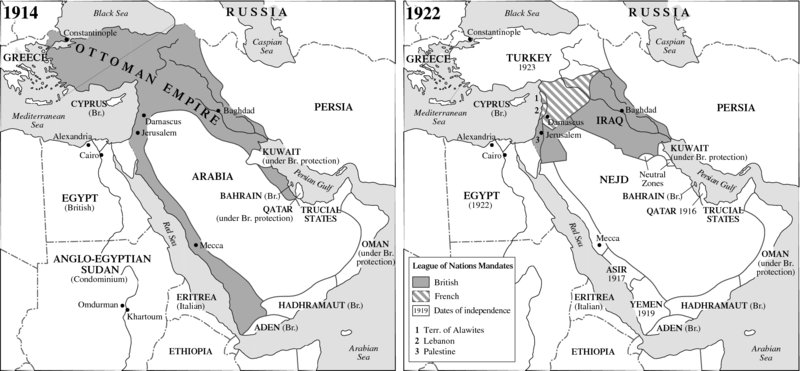

Sykes almost got his wish. The present-day Iraqi border with Syria and Jordan begins in the west not far from the Lebanese city of Acre and extends in nearly a straight line north and east toward Kirkuk in Iraq before jogging north to Turkey. The borders of Iraq were drawn when the League of Nations was created in 1919 soon after the end of World War I. That is to say, the nation-state of Iraq was a twentieth-century invention, and it was created by cobbling together the three separate provinces of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra that had been under Ottoman rule. Indeed, the entire Middle East is a product of lines drawn primarily to serve British civilian and military ambitions. T. E. Lawrence, the famous Lawrence of Arabia, is rumored to have bragged that he and Winston Churchill had designed the modern Middle East over dinner. Whatever the truth of the boast, by 1922 the deed was done (see

Map 4.1

).

Map 4.1

The Middle East before and after World War I settlements, 1914â1922.

The end of World War I coincided, more or less, with the end of the Ottoman Empire. With its partitioning among the Allied Powers of Europe, some consideration was given to creating an independent state for the Kurds, who speak Kurdish, an Indo-European language, which makes them one of the largest non-Arabic-speaking populations in the region. However, no proposal was agreed upon, no separate state was created, and a significant Kurdish population found itself drawn inside the lines of northern Iraq. Seventy years later, in 1990, another conflict involving the West erupted in the region, and the Persian Gulf War began with Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. At the end of the conflict, United States President George H. W. Bush went on Voice of America Radio and encouraged Iraqis to “take matters into their own hands.” The Kurds, perceiving weakness in the government, saw their opportunity to take control of their fate, but Saddam Hussein managed to quell all popular uprisings. The result was the mass departure of nearly two million Kurds, who left Iraq mostly on foot. The problem was, given the historical contingencies, the Kurds had no particular place to go.

In this chapter, we trace the rise of the nation-state in Western Europe and seek to illustrate how it came to be solidified during the course of the eighteenth century. As we will see, nation-states came to cohere around the one nation, one language ideology, which created at the same time a new association between a particular language and a particular place â and a particular place to go was exactly what the Kurds were lacking when they walked out of Iraq. The disenfranchised Kurds leverage our understanding of nation-states as human creations, not timeless and universal realities, and give us a wedge into exploring the various ways language and place-based political identity have been put to strategic use in order to construct and maintain states and to contain and constrain the speakers within those states. We end the chapter by looking at some of the bedeviling effects of a sometimes hidden third term standing alongside of one nation, one language ideology, and that is

race

.

Language has not always been central in the organization of political structure and identity, nor have languages always been delimited by precise boundaries. The rulers of the monarchies and empires antedating the modern European nation-states did

not concern themselves with the languages their subjects spoke, nor did they perceive the boundaries of their realms as fixed, since they waxed and waned with wars and marriages. In pre-eighteenth-century Europe, dynastic power was concentrated in centers and radiated out over large expanses to somewhat fluid borders. Dynastic legitimacy was secured by divine right, and identity cohered around religion. For many centuries, religious diversity was perceived as a threat, while linguistic diversity was simply a fact of life. However, during the eighteenth century, attitudes surrounding language began to shift in concert with the reorganization of political power. The ruling powers sometimes did and sometimes did not take heed of the winds of change. In either case, still today many places across the landmass Eurasia are dealing with the linguistic fallout of the dissolutions of the Holy Roman Empire (962â1806), the Russian Empire (1721â1917), and the Ottoman Empire (1453â1922).

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II,

1

House of Habsburg and leader of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruled over speakers of a wide variety of languages, including Hungarian (aka Magyar), which is Uralic, as well as Croatian, Slovakian, Ukrainian, Italian, and Austro-German, all of which are Indo-European. In the 1780s, he made the decision to change the administrative language of the empire from Latin to German because he deemed the mediaeval Latin of the nobility unsuitable to carry out the needs of the masses. (Perhaps he caught the whiff of a populist scent coming from the Americas.) He chose German not because he felt a special allegiance to the German language, culture, or people as such, and he was certainly aware that many of his own relatives did not speak this language. Rather, he made his choice based on the fact that of all the languages in the empire, German had the most developed cultural and literary tradition, as well as the fact that there were significant numbers of German speakers in all parts of the empire. The emperor's choice was pragmatic.

2

In retrospect, it also looks natural. In the context of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was unremarkable that many members of the House of Habsburg did not speak German. However, in the context of twenty-first-century nationalisms, it is difficult to imagine a member of the German Bundestag (Parliament) not being able to speak German.

Similarly, it would be difficult to imagine any president of Russia not being able to speak Russian. However, the Tsarist Romanovs spoke French at their court in St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century, while much of provincial nobility spoke German. It took 20 years after Napoleon's 1812 siege of Moscow for a sense of Russian nationalism to begin to circulate in the Russian court, but it was not until Alexander III (1881â1894) that Russification became official dynastic policy. Before the nineteenth century, however, the Romanovs, like many Habsburgs with respect to German, had no affinity for the language of the people in whose midst they lived, namely the Russians. They had no need for such affinity, because they did not interact with people outside their own circles. The Romanovs ruled over speakers of a wide range of languages, representing at least three language stocks: Finnish, a Uralic language; German, Armenian, Russian, and Latvian, all Indo-European languages; and finally a variety of Central Asian Turkic languages, such as Tatar,

3

which were brought into the empire by Ivan the Terrible in the sixteenth century. Although administrators in Tsarist Russia were not particularly interested in making language policy and could be thought of as having been asleep at the wheel around the time of the Russian

Revolution, the Bolsheviks who came in the wake of 1917 were keenly interested in matters of language, since they were determined to create a modern state.

As for the Ottomans, Ottoman Turkish, a Turkic language, was the imperial language of the Ottoman Empire and was required for official correspondence with the government. It was a lingua franca, a unifying language bridging across groups of people who speak different languages â just as Latin was an administrative lingua franca of the Holy Roman Empire, and French was the lingua franca of the cultural elites, that is, the aristocrats in Europe. Especially influential within the Ottoman Empire were both Arabic, an Afro-Asiatic language, and Persian, an Indo-European language. Beyond that, the great linguistic diversity within the Ottoman Empire was not considered a threat to imperial power, and the many languages spoken in the realm belonged to equally diverse language stocks: Georgian, a Caucasian language; Berber and Somali, Afro-Asiatic languages like Arabic; Hungarian, once again, Uralic; Greek, Kurdish, Romanian, and Ukrainian, all Indo-European languages. No one could have guessed that when the Ottoman Empire came to an end, nation-states called Georgia, Somalia, Hungary, Greece, Romania, and Ukraine, all articulated around national languages bearing their name, would have come into existence but not a state called Kurdistan.

When these empires fell, and new political units organized themselves around the idea of the nation, one resource that had previously been mostly unremarkable to the political elite â namely language â found a central place in this reorganization. Nation-states came into being at the same time their titular national languages came to be recognized as such. To say it another way, when the state reorganized itself along linguistic lines, the nation came into being.

Despite being a relatively recent form of political organization, nations, with their cultural, political, and military apparatuses and their corresponding ideologies of nationalism, are driving forces in world politics today. Indeed, much of the conflict of the world is over the resources, spaces, and identities thought to be owned or contained within certain nations. Among the resources nations try to harness and control are the languages spoken within their boundaries; and nations, with their laws, services, and schools, are invested in controlling them by classifying them, for example, Variety A counts as a language, while Variety B counts as a dialect. In the political ideology of nationalism, language and the nation-state are one, while dialects are inconvenient residues to be marginalized, swept under the rug, or erased altogether. The one nation, one language ideology is the reason we have insisted on understanding

language

and

dialect

as sociopolitical terms in this book. It is also the reason linguists, who wish to step outside these classifications in order to get a perspective on them, choose to speak in terms of language

varieties

, a politically and historically neutral term.

When the empirical realities about place and language change, thereby engendering new forms of identity and citizenship and civic life, so also do the ways people think about these new realities change. We call this transformation

epistemological

. We define an epistemological framework to be a set of presuppositions, stakes, temperamental

positions, preferences, and/or stylistic attitudes taken with respect to large-scale questions. It is a set of assumptions, concepts, definitions, and distinctions through which questions get raised and answered, and by which what is deemed a fact is both made possible and constrained. An epistemological framework is an interpretive repertoire, a systematically related set of terms, often used with stylistic and grammatical coherence, and often organized around one or more central metaphors. These frameworks can be seen to be composed of interlocking discourses and ideologies, and although they are systematic, they are not always self-consistent, since humans are not famous for being strictly logical. These frameworks make up important parts of the common sense of a culture, although some may be specific to certain institutional domains, disciplines, or subcultures. Another way to understand an epistemological framework is to say that it is a way of knowing.

Epistemological frameworks can refer to historical periods such as Enlightenment versus Romanticism. Enlightenment ways of knowing typically include: a theory of progress in which the future is always better; an emphasis on reason, order, and precision; and a foundationalist and universalist understanding of human nature. As for language, it is seen as a man-made construction, a social reality susceptible to reform and so-called improvements based on reason. We can call this the

political conception of language

. Recall from Chapter 3 that prescriptive grammar was a product of the eighteenth century. The Enlightenment is furthermore closely associated with eighteenth-century France.

By way of contrast, Romanticist ways of knowing typically include: the notion that things were better in the past; an emphasis on emotional punch; and the relativist recognition that people and cultures are different one from the others. As for language, the life and growth and even death of language are solely in the province of

das Volk

, the nameless, faceless masses; no one person or group can intervene in the process of language change. We can call this

the organic conception of language

. Recall from Chapter 3 that Bopp and Grimm were devoted to historical reconstruction. Their goal was to uncover the original language, or

Ursprache

, the one before time has withered it, corrupted it. Recall again that Grimm thought the sound correspondences he identified were the unconscious work of the independent spirit of the German people. Romanticism is closely associated with nineteenth-century Germany.

The most important take-away from this discussion of epistemological frameworks is the idea that in the absence of a competing way of knowing, the one prevailing in a group, a community, a nation, and/or the world is called

reality

. We find the reality of nations inscribed on maps with well-defined borders, which at times are physically instantiated in walls and fences separating one nation from the next. Although language does not fit neatly within these national borders, it has been successfully mobilized since the eighteenth century as one among the symbolic resources recruited to construct nations. Other well-known symbolic resources include flags, pledges, great seals, national anthems, and certainly money. We have tangible evidence of our identities in our driver's licenses, our social security cards, and our passports, and we all have relationships with the Department of Motor Vehicles, the Internal Revenue Service, and border guards. There is a convergence between the immaterial (linguistic) and the material resources, in that the material resources consistently use one variety of a language, the standard variety. The convergence is so complete that many times a

nation and its primary national language are synonymous, such that it is now seemingly self-evidently true to say: “In France, they speak French. In Spain, they speak Spanish.” These statements, however, assume that languages such as French and Spanish are things existing in clearly defined forms differentiated from other languages. They assume that France and Spain are timeless places with clearly defined borders and homogeneous ethnic populations, namely the French and the Spanish. Even in an immigrant, ethnically diverse nation such as the United States, it is a truism to say that Americans speak English.