Languages In the World (9 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

A recent study of infant cognition found that French infants were unable to discriminate between sentences read in Dutch and English, but were able to discriminate between sentences read in Japanese and English. The researchers believe that this is due to the fact that Dutch and English have similar systems of rhythm, while Japanese and English do not. The babies were using cues in the rhythmic properties of the languages to recognize their mother tongue, which the researchers measured with pacifier suckling rate. Researchers have also found that elephants can tell certain human languages apart and even determine human gender and relative age from listening to people speak. In the study, elephants were played samples of two local languages over a loudspeaker. One of the languages (Maasai) was associated with poaching practices, while the other (Kamba) was not. While the elephants remained calm when listening to Kamba, they retreated when hearing Maasai.

First, individually or in teams, describe what the studies show about the ways in which the language loop involves human cognition and coordinated action. Then, construct a visual representation of the language loop that illustrates these points. Your visual can take any material form you choose, so long as you are able to depict the major points. For an extra challenge, try and present your points using little or no text. Present your visual representations of the language loop to the class (Nazzi

et al

. 1998).

Does the discussion of the language loop in the first part of this chapter alter your views of human language? How so? What was the most surprising, interesting, or useful thing you read in this section?

What does it mean when the authors write “human language emerged out of primate cognition and is continuous with it?” Have you heard this type of argument before?

What does it mean to say that language is an intersubjective phenomenon? How does the intersubjectivity of language operate in your life, both in terms of the ways you acquired your language(s) and in terms of the ways in which you use your language(s)?

Unless you live in Australia or have studied linguistics or cognitive science previously, chances are you have never heard of the language discussed in this chapter, Guugu Yimithirr. Why do you suppose you have not?

In this chapter, we introduce the notion of language ideology. There are many ideologies about language; one of them is known as standard language ideology â a set of beliefs about what language is or should be. First, how do you observe standard language ideology to operate around you in your own speech community? Second, how has reading this chapter challenged your own ideological beliefs about language?

- Comrie, Bernard (ed.) (1987)

The World's Major Languages

. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis. - Enfield, Nick (2002)

Ethnosyntax: Explorations in Grammar and Culture

. Oxford: Oxford University Press. - Levinson, Stephen (2003)

Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity

. New York: Cambridge University Press. - Nazzi, T., J. Bertoncini, and J. Mehler (1998) Language discrimination by newborns: Toward an understanding of the role of rhythm.

Journal of Experimental Psychology

24:756â766.

- Andresen, Julie Tetel (2013)

Linguistics and Evolution: A Developmental Approach

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Foucault, Michel (1971) The discourse on language.

Social Science Information

10: 7â30. - Foucault, Michel (1994)

Ethics. Subjectivity and Truth. Essential Works of Foucault 1954â1984, Volume I

, edited by Paul Rabinow, translated by Robert Hurley and others. New York: New Press. - Hall, Stuart (1997)

Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices

. London: SAGE. - James, William (1981b [1907])

Pragmatism

. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. - Milroy, James (2005) Some effects of purist ideologies on historical descriptions of English. In Nils Langer and Winifred V. Davies (eds.),

Linguistic Purism in the Germanic Languages

. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 324â342. - Tomasello, Michael (1999)

The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Tomasello, Michael (2003)

Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Wexler, Paul (1974)

Purism and Language

. New York: Indiana University Press. - Whitney, William Dwight (1875)

The Life and Growth of Language: An Outline of Linguistic Science

. New York: D. Appleton. - Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes (2007)

American English: Dialects and Variation

. 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

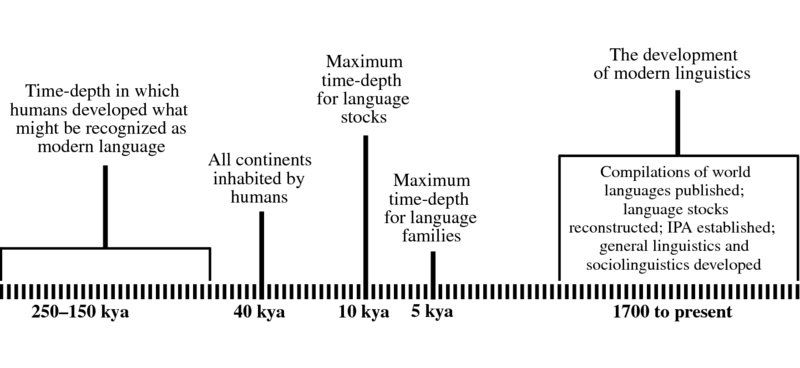

Linguistics and Classification

In 1778, William Jones, a lawyer in London with a taste for politics, heard the news that one of four Supreme Court judge positions in India was open. The judges were all appointed in England, because by that time, the Persian Mughal Empire in India had come under the military and administrative rule of the British East India Company. Jones knew he wanted the judgeship. No one else in England â or Europe, even â was better versed in the Orient than he was. He knew Persian fluently, a key skill for someone working for the Company, because Persian was the language used by native

princes in their letters to the Company. Jones also knew Mohammadan law, another key skill because the former rulers of the territory the Company had encroached upon were Muslim. Jones wanted the post mostly for the salary. The judgeship paid £6000 a year. He figured he could save £20,000 in five years, return to England, and go into parliament (Cannon 1964:55).

Five years later, he finally made it to Kolkata (Calcutta) in the Indian state of Bengal.

1

He had a life-long passion for social justice and quickly discovered major injustices in the court system toward Indians. He determined that if there were a good system of laws and a just administration of them, there would be long-term peace, not to mention prosperity for Great Britain. He immediately encountered one large problem: he did not know Sanskrit. When hearing a case, a lawyer might cite a point, no matter how illogical, and claim it to be part of Hindu code. Jones had no alternative but to accept it. Knowing well the pitfalls of translations, he was wary of depending on Persian versions of Hindu laws, and he was unimpressed with the single English translation that existed of an original Sanskrit law code. So, he set out to learn Sanskrit, whereupon he encountered another large problem: no Brahman would take him on as a student, and this caste was the keeper and preserver of the sacred language and its manuscripts. Even when he assured the Brahmans he would not defile the religion by asking to read the Vedas, no one would help. Eventually, he found a

vaidya

, a medical practitioner, who knew Sanskrit but who himself was prohibited from reading certain texts, to teach him. Over the next few years, Jones applied himself to learning this important language.

Having been well educated at Harrow and University College, Oxford, Jones also knew Greek. It did not take him long to see that the Greek word for such a common verb as âI give,' namely

dÃdÅmi,

was very similar to the Sanskrit word for âI give,' namely

dádÄmi

. In fact, he found the verbal paradigms of the two languages to be remarkably coincident, along with great stretches of vocabulary. In 1786, in his Third Anniversary Discourse to the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal (a society he himself established), he had determined that ancient Sanskrit and classical Greek and Latin bore “a stronger affinity,” as he put it, “both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source.” He went on to suggest that Germanic and Celtic as well as Old Persian were also likely related. This discourse was the first and clearest expression of the possibility that Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin, and perhaps others, were divergent later forms of some single prehistoric language.

Although Jones's works on Hindu law did form the basis for much of Indian jurisprudence for the next hundred years or more, he was never able to see through his list of judicial reforms. Neither did he ever return to England, for he died in Kolkata at the age of 48. He did, however, make a lasting contribution to language studies for pointing scholars to the right path for working out the historical relationships among the languages of Europe and South Asia. It is the focus of this chapter to summarize the major kinds of classifications of the world's languages â historical, areal, typological, and functional â that linguists have developed in the more than two centuries since Jones's Third Anniversary Discourse.

In Chapters 1 and 2, our effort was to discuss the dynamics of the language loop in terms of the historical, cultural, and cognitive dimensions in which it is instantiated, developed, and maintained. Another way of saying this is: individuals â no matter what linguistic activity they are engaged in, be it speaking, signing, listening, reading, or writing â are always in one context or another. They have been so since the beginning of the time we identify humans as such; they are so from the moment they are born. However, there are important traditions of study that take languages out of context in order to compare and contrast them, and to see what kinds of understandings fall out from comparative process. In this book, we call the practice of taking language out of context in order to study it

philology

.

The modern use of the classical term

philology

was created in Germany toward the end of the eighteenth century. A student named Friedrich August Wolf refused to register in any of the four faculties that then constituted the entire university curriculum at Göttingen University: philosophy, medicine, law, and theology. Wolf wanted to study the ancient Greeks, and so he was advised to register in the theology division, because Greek was part of the training it offered. Wolf insisted that he did not wish to study Greek in order to read the New Testament; he wanted to learn Greek in order to study Homer. He was finally enrolled as

studiosus philologiae

. During the course of the nineteenth century, a distinction came to be made between literary and linguistic scholarship, and the term

philology

came to settle on the study of language, which meant the comparative study of the Indo-European languages for the purpose of reconstructing their history.

In the early nineteenth century, the term

linguistic

was reserved to refer to the databases of the world's languages that had been expanding since Columbus and that had reached global proportions by the early-to-mid nineteenth century. Since the seventeenth century onward, the term

linguist

had been uniformly equivalent to

polyglot

, that is, âsomeone who speaks many languages.' The early comparative philologists, the most prominent being Franz Bopp and Jacob Grimm, did not refer to their own work as linguistics. By the way, Jacob Grimm is one of the Grimms of fairy tale fame. In order to write his

Deutsche Grammatik

of 1819 (Grimm 1819), he and his brother were inspired to collect fairy tales told in varieties that might have preserved some of the oldest forms of the language. He and his brother were also motivated by the belief that in popular culture could be found national identity, which was the possession of

das Volk

, or the (common) people. The early work in comparative philology was also tinged with beliefs about German national identity and, in fact, helped create that identity. When Grimm formulated The First Germanic Sound Shift, also known as Grimm's Law, it was his belief that the cause of the shift was the independent spirit of the Germanic people. We will explore the relationship between language and nation more explicitly in Chapter 4.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the term

linguistics

came to mean âthe science of language,' and comparative philology was retroactively dubbed comparative linguistics. Linguists are now students or practitioners of linguistics, and they may or may not speak many languages, although popularly and in certain contexts, the

term

linguist

can still mean âpolyglot' and/or âtranslator.' Linguists are furthermore devoted to discovering the descriptive rules of a language, that is, how people

do

speak. Linguists thus distinguish themselves from grammarians, who design prescriptive rules for how people

should

speak. Prescriptive grammar arose in the eighteenth century, and the English-language grammarians Robert Lowth and Thomas Sheridan, for instance, laid down rules still taught in American high schools and style manuals today: don't split an infinitive; don't end a sentence with a preposition; when speaking of two items, the word

between

is to be used, and when more than two are at issue,

among

is to be used; don't use a double negative; don't use a double modal; don't use the word

ain't

, and so forth.

Linguists, by way of contrast, believe that what native speakers say is by definition correct, and they are therefore interested to observe and understand what people do say. Many speakers of any number of varieties of English use double negatives:

I don't got none

or

I ain't got none

, while speakers in the parts of the American South may combine modal verbs such as

might

,

should

,

could

, and

would

in an utterance such as

I might should do my homework.

Some of these variations are regional, while some correlate with the socioeconomic status of the speaker. From a linguistic point of view, they are all correct.

We have rehearsed the brief history of the terms

linguistics

,

philology

,

linguist

, and

grammarian

here in order:

- to note that the judgments grammarians make about language and those that linguists make are quite different;

- to reintroduce the term

philology

and to define it as âthe study of language for its own sake,' that is, âthe study of language when taken out of context'; and - to recognize the effort of this book in terms of the original meaning of the word

linguistics

, that is, as a contribution to the amassed knowledge of the living languages of the world.

Our effort is now to ally this body of knowledge to work in the social and biological sciences. We are dedicated to a linguistics that provides thick descriptions of the various dimensions of the dynamics of the language loop, here only outlined.

Bopp and Grimm were comparative philologists. They, among many others, took the ball Sir William Jones got rolling and engaged in the grand nineteenth-century project of reconstructing the Indo-European languages. Scholars in Europe had suspected since the Middle Ages that the languages spoken in Europe came from some source and perhaps from a single source, the most likely candidate being Hebrew. However, efforts to connect European languages to Hebrew were unsuccessful. In the sixteenth century, a Scythian hypothesis was first proposed to account for the unity of European languages, the Scyths being an equestrian people who inhabited the Eurasian steppe in antiquity and who were known to the Greeks and Romans. This hypothesis received some attention over the next few centuries, but the proposal remained vague. Then came Jones and his startling hypothesis.

It was left to succeeding generations of philologists to work out the details of the relationships among the Indo-European languages through the process of

linguistic reconstruction

, and comparative philology became known for its methodological

rigor. The reconstructive process is necessarily a retrospective activity, a jigsaw puzzle put together from present-day pieces and historical records to make a picture of a source language. The name Indo-European is geographic and indicates the eastern and western historical (pre-Columbian) boundaries where the languages are spoken. The name given to the reconstructed language itself is Proto-Indo-European (PIE). A reconstructed

protolanguage

is a common ancestor language that spawned at least one descendant. For instance, Proto-Romance is the term given to what is popularly called Vulgar Latin, which gave rise to French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian. Many of the protolanguages we will be referring to in this book are prehistoric, and these are pictures of source languages as they might have existed before written records.

2

Thus, languages such as Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin are prized among the Indo-European languages, because they have the oldest written records and therefore bear evidence of forms that might be closest to what could be hypothesized as the original.

Latin, in particular, was valued because the Romans produced two things of linguistic relevance: an empire whose legacy lives on in the many daughter languages of Latin, known as the Romance language

family

,

3

and a rich classical literature. In addition, this culture of writing extended to the earliest stages of the various Romance languages. Because of these factors, the Romance branch of Indo-European was used to test reconstructive methods. When a word or a grammatical construction is found in a written record, it is attested. If a form is reconstructed, and there is no written record to show evidence of it existing in exactly that form, it is unattested and marked with a

*

, exemplified here with the reconstructed PIE root

*

b

h

er-

âto bear, carry.' This root comes attested into English as

bear

, into Latin as the root

fer-

, into Greek as the root

pher

-, and so on. Romance philologists wisely did not use the rich inventory of Latin manuscripts proactively. Rather, they used them retroactively. If the philologists were able to reconstruct a historical source word from the modern Romance languages or from the historical records of these languages, and if they were able to find that word exactly attested in a Latin manuscript, then their reconstructive methods were confirmed. The Latin database served as a strong methodological backstop.

One of the most important reconstructive principles is that of the regularity of sound change. We see this regularity when we compare varieties of a language, say, American English. Northerners pronounce the first person pronoun âI' with the double vowel, or diphthong, [ai]. Southerners pronounce it with the single vowel, or monophthong, [aË], which in this case is long. The fact is, this sound correspondence [ai]â¼[aË] is regular. It holds across all instances of the Northern and Southern pronunciations of this vowel. We also see this regularity when we compare cognates from related languages, such as the English, Greek, and Latin cognates for the PIE root

*

bher-

that all have a meaning similar âto carry.' The differences in their pronunciations will be accounted for, below. Another example would be English

wagon

and German

Wagen

âcar' pronounced with an initial [v], with both forms meaning something like âa wheeled conveyance.' The sound correspondence [w]â¼[v] also holds between English and German in many pairs of cognates, such as:

white

â¼

weiss

,

week

â¼

Woche

,

while

â¼

weil

,

wonderful

â¼

wunderbar

, and so forth. These are stable correspondences. English speakers do not slip up and on occasion say “Oh, that's vonderful.” They regularly pronounce a [w] where the Germans pronounce [v].

Grimm introduced the principle of the regularity of sound change in 1822 when he proposed the following set of sound correspondences, here simplified:

| PIE: | * p | * t | * k | * b | * d | * g | * b h | * d h | * g h |

| â | â | â | â | â | â | â | â | â | |

| Germanic: | * f | * θ | * h | * p | * t | * k | * b | * d | * g |

Note: the superscript [

h

] stands for an aspirated consonant, one that includes a little puff of air.

Expanding these correspondences to include Latin and Greek, we have the series, again simplified, of attested sounds:

| Latin: | p | t | k | b | d | g | f | f | k |

| Greek: | p | t | k | b | d | g | p h | t h | k h |

Grimm's Law captures one of the major differences between the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and, say, Greek and Latin, which retained most of the original sounds inherited from PIE. So, all instances of PIE

*

p became

*

f in Germanic, all instances of PIE

*

t became

*

θ in Germanic, and so forth. English perfectly exemplifies Grimm's Law because it is a Germanic language with so many Latin borrowings through French. Thus, finding pairs of words showing the correspondences is easy. For instance, when seeking the identity of the

f

ather of a baby, a

p

aternity test might need to be administered. When you want the car to go faster, you put your

f

oot on the

p

edal. In the zodiac, the sign of the

f

ish is

P

isces. A person who likes to play with

f

ire is called a

p

yromaniac. These pairs are extremely robust in English for all of the correspondences. As for the case of the PIE

*

[b

h

], the expanded form of Grimm's Law shows that this sound regularly became the fricative [f] in Latin and the devoiced aspirated stop [p

h

] in Greek, thus explaining the pronunciation of the cognates for

*

b

h

er-

âto carry' in those languages, mentioned above.

It is of interest to note that Indo-European was not the first language

stock

4

to have been accurately proposed. This honor goes to Uralic, also known as Finno-Ugric, whose identification dates to 1770.

5

This language stock includes Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian, and Samoyed spoken in Siberia. It is the only other multilanguage stock found in Europe. There is the case of Basque, a non-Indo-European language spoken in northern Spain. However, Basque is considered to be a language

isolate

, which is equivalent to saying it is its own stock. At some point in the distant past, it had to have been related to other languages. However, those languages are now gone. Some linguists consider such well-known and well-studied languages as Korean and Japanese to be isolates, as well. Some linguists class one or the other or both in the Altaic language

phylum

.

6

The language stocks of the world will be discussed in Chapter 7.