Languages In the World (18 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

The Development of Writing in the Litmus of Religion and Politics

According to Islamic tradition, the Qur'Än is a book of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. It did not come to him in the form of a complete book but rather in parts over a period of several decades. The first part was revealed in 610 at

Jabal an-Nur

âThe Mountain of Light' near Mecca when the Prophet was 40 years old. A few years later, he began his public preaching. Thereafter, different parts continued to be revealed to him until his death in 632. Before the time when the Qur'Än was revealed, the Egyptians had already invented a good writing material made from the

papyrus plant. Whenever any part of the Qur'Än was revealed, scribes wrote it down on papyrus or

qirá¹as

in Arabic. During this process, people also committed the verses to memory so that they could recite them during prayer.

1

Thus, the Qur'Än continued to be simultaneously memorized and written down, and this method of preservation continued throughout the lifetime of the Prophet.

The most important part of this story, from the point of view of the present chapter, is the fact that the Prophet is said to have been illiterate. The belief in Mohammad's illiteracy secures the belief in the Qur'Än as the word of God in two ways. First, Muhammad's illiteracy underscores his simplicity, making him an appropriate conduit through which the word of God could be revealed. Second, Muhammad's illiteracy preemptively removes doubt that these words could come from a source other than God, because an illiterate man could not have created a work of such beauty and complexity as the Qur'Än. History tells us that Muhammad was a successful merchant before his call as a messenger prophet, so he must have known how to count. During his time, letters were used to represent numbers in Arabic, as they were in all Semitic languages, including Hebrew.

2

So, it is possible that Muhammad knew how to write and record a transaction. Our purpose here is not to offer an opinion on the state of Muhammad's literacy; it is rather to emphasize the fact that, despite potential evidence to the contrary, the belief in Muhammad's illiteracy is bound to the conception of the Qur'Än as the direct word of God. The further implication is that once the divine word has passed through the human agent, the writing down of those words can be regarded as a sacred act. It is but a small step to make the inference that writing itself is a divine creation.

The story of the Qur'Än serves three purposes for this chapter. First, it illustrates the intertwined relationship between religion and the written word. Second, it suggests the power of the written word, and this power, as we have just seen in Chapter 4, circulated forcefully enough throughout the eighteenth century in the form of print capitalism to reinforce a new political entity known as the nation-state. In this chapter, we will see that the power of the written word as the word of God often goes hand in hand with political power. Third, the story of the Qur'Än brings attention to the dynamics of orality and literacy in that the development of religious tradition drives not only particular linguistic practices (prayers, chants, etc.) but also the very scripts used to represent languages.

3

The multifaceted relationship between religion and writing is wrapped in layers of legend and mystery. The oldest known writing system was created in Mesopotamia, that of the cuneiform (Latin

cuneus

means âwedge') script of the Sumerians whose cultural and linguistic origins are not well known. When the Akkadians migrated into the area in the fourth millennium BCE, they adapted the cuneiform script of Akkadian, a Semitic language, and revered Sumerian as the sacred language of the priests. At about that same time, the Egyptians had gone beyond decorating pottery with pictures of animals, birds, and symbols of deities, and were carving onto their temples and tombs

interpretable narratives in a pictorial word-script. The Egyptian god Thoth was one of the most important of the deities, and the Egyptians believed him to be responsible for inventing, among other things, religion and the alphabet. In the second century CE, the Greeks gave the Egyptian pictorial word-script a lofty name: hieroglyphs (

hiero

âsacred'

glyph

âcarvings'). The Greeks believed hieroglyphs to be mysterious symbols that could only be interpreted mystically, since the priests who once wrote and read them were long gone. It was not until the twentieth century that these symbols were successfully deciphered.

Halfway around the world, the two great civilizations of Mesoamerica, the Aztecs in central Mexico, who spoke Nahuatl, and the Maya on the Yucatan Peninsula, who spoke Mayan, produced separate scripts that post-Columbian scholars both called

hieroglyphs

. When the first Spanish expeditions arrived in the early sixteenth century, the Aztecs were already in possession of an abundant literature. Surviving manuscripts, written on deerskin or a kind of paper made from the bark of fig trees or from agave fibers, are mostly historicalâmythological or calendricalâastrological in content. The custodians and experts of this writing were the priests. With respect to the civilization of the Mayan people, who also created both a type of paper and a complicated picture script, religion once again plays a role, albeit an unhappy one. The Franciscan Bishop of Mérida, Diego de Landa, took enough interest in the Mayan hieroglyphs to attempt to relate them to the letters of the Spanish alphabet â a method of decipherment that proved unsuccessful. Unfortunately, de Landa's interest in the script did not extend to a desire to preserve it. In 1562, he ordered the burning of many Mayan religious symbols and writings, such that today only four manuscripts remain of the dozens that were produced. The Aztec treasures had fared no better. Following the earlier conquest of Mexico by Cortez, the Spaniards burned their books, as well.

Examples of a belief in the religious or mysterious origins of scripts abound. In India, the curly cued script known as

DevanÄgari

means âthe script of the City of the Gods' (

deva

âGod';

nÄgari

âcity') and is used for writing Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, and so forth.

4

In Eastern Europe, the name of the Cyrillic alphabet comes from one of the two ninth-century Christian apostles, the brothers Constantine (later called Cyril) and Methodius, who adapted the Greek alphabet for a language known as Old Church Slavonic, so called in reference to the literature recorded in it. In reference to its genetic classification, this language is known as Old Bulgarian. The Cyrillic alphabet was later adopted for use by many Slavic languages, including modern-day Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, and Ukrainian, and some non-Slavic languages, such as Mongolian. In Africa, the Nsibidi script is used to write Igbo and Efik, both spoken in Nigeria and both NigerâCongo languages, and those who use this script believe it to be a means of magic. Although the meaning of the name of this script is disputed, some suggest that

sibidi

means both âto play' and âto bewitch' (Jensen 1969:217).

A sense of mystery and magic of the written word can be found in English, as well, in the word

spell

that refers not only to how words are written but also to a set of words with supernatural powers. The Germanic languages were originally written in an alphabet known as runes. In Old English, the word

rune

meant âmystery' or âsecret.' In one variety of Norwegian the noun

runa

means âa secret formula,' while the verb form means âto cast a spell.' In modern German,

raunen

means âto whisper' and in Irish, a Celtic language, the word

rúnda

is translated as âa secret.'

Although the Sumerians' cuneiform is considered to be the oldest established writing system, the Chinese script can claim the distinction of being the oldest writing system still in use today. It is at least 3000 years old. In one Chinese tradition, the invention of the script is attributed to Ts'ang-Chieh and Chu-Sung, two secretaries in the court of the Yellow Emperor or Huangdi in the third millennium BCE, to whom divine honors were later accorded as

tzi shen

âdieties of writing.' According to legend, the secretaries gazed high in the sky to the constellations and low into the ground to the traces left by animals and the patterns found on tortoise shells. Out of the beauty of these curves came writing. When the first writing was composed, so the legend goes, the ghosts wept because the spirits could no longer hide their shapes from humans.

Divination is the practice of âreading the signs of the universe' in an attempt to interpret God's plan. In China, archeological discoveries of bones and tortoise shells give evidence that divination was practiced from the earliest times. Upon these bones and shells were etched questions concerning weather or crops or military operations. Heat was then applied until the bones or shells cracked, and the people who knew how to read the cracks, namely the priests, were asked to interpret them. In early Germanic times of several thousand years ago or more, priests cast onto the ground

staben

âsticks/staffs' from the

buch

âbeech' tree and then interpreted the meaning of the pattern of the sticks as the priests gathered them up. The modern German lexicon bears traces of this magical practice: the word

buch

means âbook,'

Buchstabe

means âletter (of the alphabet),' and

lesen

means both âto gather' and âto read.'

Thus, from the earliest times, writing â certainly a human invention â was associated with the divine or the magical, and this association invested the written word with a power that was to be guarded by a restricted inner circle of the initiated, that is, by the diviners or the priests.

People from language groups and cultures all over the world have devised ways to communicate with one another through objects. An X scratched into the ground can mark the spot one human either wants to remember or wants another human to notice. A pile of stones can serve as a landmark or monument, and, indeed, man-made stacks of stones are found all over the world. Stones on a grave â put there for whatever reason â over time came to be interpreted as a âmemory'-al â whose original meaning is now often forgotten in the word

memorial

, which takes the form of an engraved headstone today. To mark paths, hunters and migratory people often scatter grass or leaves or set up sticks.

Different types of objects serve communicative purposes. A notched stick, or tally (cognate with English

till

and German

zählen

âto count'), can be used to record lines of ancestry or commercial transactions involving debts and credits.

5

A messenger stick calls dispersed peoples to meetings. Woven objects serve varied purposes. Among the speakers of Iroquois and Algonquin in North America, belts were made up of four or more strings; on each string were rows of shells bored through the middle. These came

to be called wampum belts after the Iroquois name for the shells, namely

wampum

. Depending on the design of the shells, war or peace or a truce could be declared. Another type of woven object, the knotted cords of the quippu of the Incan empire of western (Andean) South America, had enough importance to have been read only by special officials, the

quippu camayocuna

.

6

Although the exact use of the

quippu

has been lost, scholars have suggested that they might have recorded chronicles, legal codes, literature, and inventories, or even made astronomical predictions. Turning once again to China, Lao Tzu noted the use of knotted cords in his

Tao-te-ching

of the sixth century BCE. Such cords were in use even into the twentieth century of our era on the Ryukyu Islands in the East China Sea southwest of the Japanese island of Kyushu. Other objects, such as badges of ranks and symbols of professions, count as object writing, with the red-and-white-striped pole of the barber being but one example.

Although all cultural groups have devised what can be called object writing, not all cultural groups have created a system to represent a specific sequence of sounds, what can be called writing proper. Objects such as stones, sticks, tallies, belts, cords, and badges have never been transformed into representations of acoustic signals. However, acts such as painting, scratching, and scoring have historically provided the first steps toward writing, and the terms themselves in Indo-European languages tell the story. The English word

write

is cognate with Old Norse

rīta

âto scratch (runes).' Latin

scribere

âto write' is also etymologically âto scratch, to score,' as is the original meaning of the Greek word âto write,' namely

graphein

, which in turn is cognate with German

kerben

âto notch' and English

carve

. The Gothic word

mÄljan

âto write' corresponds to German

malen

âto paint'; the relationship between painting and writing is again found in the Russian word

pisat'

âto write' and the Polish word

pisaÄ

âto write,' and these are cognate to Latin

pingere

âto paint' from which the English word

paint

comes.

Similar associations can be found outside of the Indo-European languages. In Chinese, the word for âscript-sign'

wen

1

(

æ

) means at the same time âornament.' Similarly,

kirja

means âbook' in Finnish but also âan embellishment, bright colors.' In Fijian, the word

tusi

denotes âstriped, colorful material,' while in Samoan, the same word means âwriting.' In the Semitic languages, one finds the Assyrian root

Å¡- á¹ -r

âto write' cognate with Arabic

sÄá¹Å«r

âa big knife,' while the original meaning of the Semitic triliteral root

k-t-b

âto write' is preserved in the Syrian word

makt

Ç

bÄ

âan awl.' Note, first, that the Syrian word has the prefix

ma

-, which is used to form a word for an instrument, in this case a cutting instrument; and note, second, that the vowels only modify the main meaning of the word, which is expressed by the three consonants

k

,

t

, and

b

.

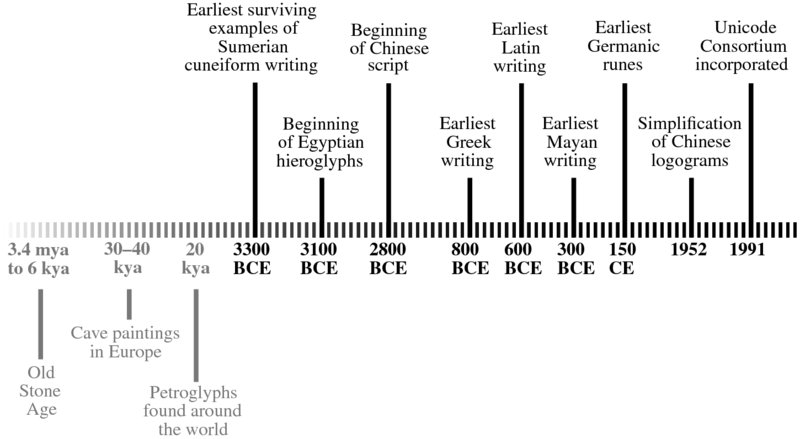

The act of drawing â painting, scoring, scratching, etching â to create pictures for communicative purposes is the first step toward writing, but it is not yet what linguists consider to be writing. Humans have been drawing with great sophistication for many millennia. In 1940, cave paintings at Lascaux, France were discovered and date back to 16 kya, while those at Chauvet, France date back to 33 kya. In Cantabria, Spain, the El Castillo cave is even older, going back to 40 kya. In 2014, seven limestone caves

on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi were discovered to have wall art, and scientists date these paintings to be likely as old as the earliest European cave art. In the caves at Lascaux, for instance, the scenes are of the hunt, and they are drawn with grace and keenly observed images of galloping horses. Although no one today knows who drew these images or what purpose they served, they certainly had a limited audience because, in order to draw them and to see them at Lascaux, it was necessary to go down a shaft on a 20-foot rope with a lamp. Some art historians speculate that these drawings were created by a priestly class of artist-shamans. Whatever their purpose, they were certainly meaningful to those who drew them and saw them.

Rock drawings (petroglyphs when carved, petrograms when painted) have been found on all continents, the oldest in Europe dating back to the late Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) period, 20â10 kya. Their meanings are lost to us today. Other kinds of drawings with specific meanings include proprietary marks, such as brands for livestock and clan or house marks, as well as so-called skin-writing, also known as tattooing. Not incidentally, tattooing as a religious practice is a kind of branding, where one displays the propriety mark of one's god on one's body. Today, tattoos still often signal adherence to a specific group, be it a gang, a cult, or a military unit. In India, women wear henna tattoos in their role of bride.

The point here is that within language groups and cultures, certain pictures â whether they are drawn on cave walls, rocks, houses, pottery, or skin â can take on conventional meanings over time to become stable word-pictures of things and actions, and even abstract ideas. Two things tend to happen next. First, the number of word-pictures often increases. Second, the growing stock of word-pictures creates the need to simplify individual ones, that is, to stylize them, to abbreviate them. These abbreviations then also come to be conventionalized, such that quite a lot of technical skill is required to understand them and to reproduce them. This reproduction, furthermore, must be done faithfully, if one is going to use them to record something important, like the history of dynastic succession or religious doctrine. History shows that the people with this technical skill will always be the diviners, that is, the priestly class.

It was the ancient Egyptians who, with their complex and long-enduring civilization and with their papyrus, took the final steps toward writing.

7

The development of the Egyptian word picture-script followed the above scenario with the added twist: the distance between the original word-picture and its stylization eventually became so great that the visual association between the stylized word-picture and its meaning weakened, and the sound associated with the stylized word-picture strengthened. This transition is called

phoneticization.

The great advantage of this transition was that now an even greater number of things and concepts could be represented, since unconnected ideas or concepts, if they were homophones, could be represented with one and the same picture. These phoneticized pictures could even take on entirely new meanings when linked with other pictures. The process at issue here is known as rebus or word play. Children's primers sometimes make use of the process as an aid

to reading: a stylized bee next to a 4 can be read as âbefore.' Texters make use of the process when they choose to spell the word

great

as gr8. In sum, the key moment in the shift from the representation of things and actions and ideas to writing proper is the shift from the optical value of a picture to its acoustic value.

This process of transition can also be described as a shift from

ideograms

to

logograms

. Ideograms are culturally conventional word-pictures of things, actions, and concepts rather than specific sequences of sounds. Logograms are no longer pictures but rather abstract symbols uniformly interpreted as particular sequences of sounds. For instance, a thumbs-up sign is an ideogram. It conveys an idea, and this idea can be expressed any number of ways in English: “Good job.” “Way to go.” “Excellent.” By way of contrast, an example of a logogram in English would be the ampersand &, which is pronounced as the fixed sound sequence [ænd]. Depending on the context, the dollar sign can function as an ideogram: the sequence $$$ could be expressed adjectivally as “expensive,” “pricey,” or “costing a lot of money,” or could stand for the nouns

money

or

wealth

. The dollar sign functions more or less as a stable logogram when it is used in a price, such as $10, where it represents the fixed sound sequence [dalɹz], although this sound sequence can take on any number of phonetic substitutions such as

bucks

,

clams

,

smackeroos

, etc.

With the Egyptians, then, come the first word-pictures to have phonetic value only. Even from the earliest surviving writing on vessels dating from the First Dynasty, around the middle of the fourth millennium BCE, there is evidence that the script had added to its stock of word-pictures both syllable signs and single consonant signs (alphabetic letters). Because ancient Egyptian was a Semitic language,

8

there are a considerable number of words that could be considered homonyms, at least from the point of view of the consonants, because, as was said above, the consonants in these languages form the fixed, basic elements of the words, while the vowels modify the meanings. A syllable sign is one consisting of two consonants and derives from a word-picture that had become phoneticized. This syllable sign could be used to write any word with that sequence of consonants. Not every two-consonant word-picture turned into a syllable sign, but enough of them did to have had a goodly number in the Egyptian script. As for alphabetic letters, 24 consonant signs were created. There were no vowel signs. The Egyptian script remains extremely complicated because it carried with it over the millennia all the stages of development that had presumably come before. It is thus a composite script and far from purely phonetic.

This discussion of the Egyptian script contains two significant lessons. First, the steps toward phoneticization are the same for all writing systems in the world; and, second, the phonological and morphological characteristics of the language undergoing phoneticization affect the way the language will come to be written, as we will see in the next section.