Languages In the World (22 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

Azerbaijan is an ex-Soviet state of slightly more than nine million people in an area slightly smaller than the US state of Indiana. It borders the Caspian Sea and is nestled between Russia to the north, Georgia to the north and west, Armenia to the west, and Iran to the south. The titular language of the country, Azerbaijani, is Turkic. The majority of the people who speak it are Muslim. Like five other currently independent states in Central Asia â Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Krygyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan

16

â Azerbaijan was decolonized by default after the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. At that moment, the new Azerbaijan government faced the problem of securing their sense of nationhood, which they did in part through the well-established practice of consolidating their national language.

Of interest here is the issue of the alphabet. In the last 100 years, this population has endured three alphabet changes, and these changes help us summarize several lessons of this chapter. First, Azerbaijani was originally written in the Arabic script when the population converted to Islam, thus underscoring how the original choice of script stems from religion. Then came the intervention of politics with the Russian Revolution and the Bolsheviks who failed to Latinize Russian but who nevertheless succeeded in Latinizing the Turkic languages spoken in the territories inherited from the Tsars. This alphabet change was for the purpose of disrupting the visible relationship to Islam. Later, namely in 1939, Stalin rescinded the Latinizing policy and replaced it with a Russifying policy. Thus, Azerbaijani was transliterated into the Cyrillic alphabet, and this further shift illustrates the importance of a script as a symbol of political unity. After 1991, the Azerbaijani government had a decision to make. They chose de-Russification and embraced the Latin alphabet.

The adoption of the Latin alphabet was facilitated by the fact that a Latin version suited for the particular phonetic needs of Azerbaijani had already been produced in the 1920s. The Azerbaijanis also successfully rejected the attempt by Turkey to promote their version of the Common Turkish Alphabet. The adoption of a new alphabet is no small matter and requires the effort and expense of changing all public signage, transliterating all existing legal documents and literature, and creating anew all instructional materials. It also automatically disenfranchises a generation of adults who, in the case of Azerbaijan, were literate in Cyrillic. Two factors in particular have helped the successful transition to the Latin alphabet in Azerbaijan. First, the Azerbaijani Latin alphabet was standardized in Unicode, making its use available on computers worldwide; and second, UNESCO supported the creation of an Azerbaijani database of full texts of Azerbaijani writings called

Treasures of the Azerbaijani Language

(Kellner-Heinkele and Landau 2012:33)

[Arabic (Afro-Asiatic)]

[Arabic (Afro-Asiatic)]Arabic is the only multicountry language profiled in

Languages in the World

. Of the others profiled, Vietnamese and Mongolian are one-country languages. Kurdish is a

no-country language, as was discussed in Chapter 4. Tamil also has no titular country associated with it, although it does have official language status in Sri Lanka along with Sinhala. The political status of Tibetan changed when Tibet became an autonomous region of China and now has speakers in that region as well as in exile. Hawaiian is the language of one state of the United States. And !Xóõ distinguishes itself by being spoken by people who preserve the hunter-gathering way of life, while the others arose in the wake of the spread of agriculture. Arabic, like Tibetan and its relationship to Tibetan Buddhism, has prestige because of its identification with Islam. However, in contrast with Tibetan, Arabic spreads across 28 countries, either as the primary language of the country or as one widely spoken in it. Thus, its social and political dynamics are necessarily different than those affecting the other languages we profile.

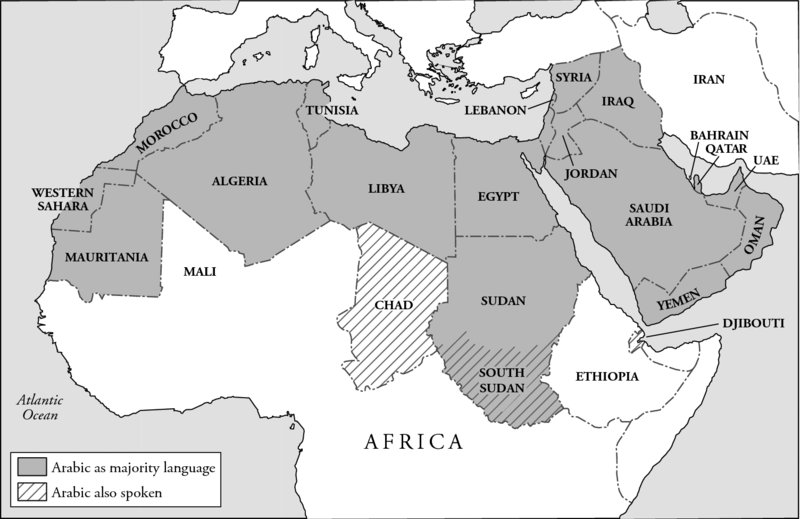

In Africa, Arabic is spoken in Algeria, Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Tanzania, Somaliland, and Western Sahara. In the Middle East, Arabic is spoken in Bahrain, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestinian territories, Qatar, Saudia Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. It is difficult to make an accurate assessment of the numbers of speakers of Arabic because it is difficult to pin down where the borders of the language start and stop over such a large geographic area, with so many opportunities for language varieties to blend. A conservative estimate is that well over 200 million people speak Arabic (see

Map 5.1

). At the same time, it is easy to think that probably upwards toward 400 million people speak some kind of Arabic.

Map 5.1

Arabic-speaking countries.

The Arabic-speaking world is distinguished by the prominent language politics surrounding the high status (H) of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the language of education, media, government, and all official occasions, and the low status

(L) of the local varieties of Arabic. The L varieties are not necessarily mutually intelligible and are sometimes referred to as

darija

âeveryday language.' MSA is, for all intents and purposes, Classical Arabic, which has remained unchanged since the seventh century, although given the linguistic dynamics prevailing at all times, certain local varieties of MSA can be said to exist. For the most part, however, it is a stable and uniform language. MSA is no one's native language; it is taught in schools, which means that every educated speaker of Arabic deals with at least two varieties of the same language (historically speaking, at least) throughout their lives and likely on a daily basis.

)

)Speech sounds are created when air comes up from the lungs and passes in different ways through the vocal tract.

17

Vowels are created when there is a modification of an open vocal tract with no buildup of pressure above the glottis. Consonants are created by complete or partial closure of the vocal tract, and they are identified by the ways the air leaves the vocal tract:

- Oral/nasal â if the velum is lowered, the air goes through the nose to produce a nasal; nasals in English include [m], [n], and [Å]; all other consonants in English are oral.

- Voiced/voiceless â when the vocal folds vibrate during a consonant constriction, a voiced consonant is produced such as [d]; if they cease vibration, a voiceless consonant is produced such as [t].

- Place of articulation

â consonants vary by the place where the full or partial constriction of the vocal tract occurs, and these places include, among others, the larynx, pharynx, glottis, velum, hard palate, alveolar ridge, teeth, and lips. - Manner of articulation

â if there is full constriction of the vocal tract, a stop sound is produced such as [d] and [t], both of which are oral and alveolar, and vary by the feature voiced/voiceless; if partial constriction of the airflow is made, a fricative is produced, such as [v] and [f], both of which are oral and labiodental, and vary by the feature voiced/voiceless; other manners of articulation exist.

MSA and many L varieties exploit a place on the vocal tract that English does not: the pharynx. There is a series of four consonants â [á¸] ( ), [á¹£] (

), [á¹£] ( ), [á¹] (

), [á¹] ( ), and [áº] (

), and [áº] ( ) â sometimes called

) â sometimes called

emphatics

, which are produced with the tongue on or around the alveolar ridge along with a constriction of the pharynx and which vary by the features voiced/voiceless and manner stop/fricative. They are so distinctive that Arabic is self-described as the

lugat aḠá¸Äá¸

âlanguage of the á¸Äá¸.' Please note that the transliterations have a dot below what corresponds to the Latin equivalent (more or less) of the sound. These dots will help you sort out Exercise 1 in this chapter.

In addition, MSA has glottal stop [Ê] called

hamza

and written ( ). It is distinguished from the voiced pharyngeal fricative with a similar-looking phonetic symbol [Ê] but written distinctively in Arabic (

). It is distinguished from the voiced pharyngeal fricative with a similar-looking phonetic symbol [Ê] but written distinctively in Arabic ( ). Its unvoiced counterpart is [ħ] (

). Its unvoiced counterpart is [ħ] ( ).

).

Controversy swirls around the exact descriptions of these sounds, and they certainly vary in their pronunciations over the vast Arabic-speaking area.

The Germanic languages once had a productive morphological process organizing the verbal system and some associated nouns and adjectives, exemplified here by the two series:

sing

â

sang

â

sung

â

song

and

wring

â

wrung

â

wrung

â

wrong

. In English, internal vowel changes to distinguish singular from plural are few, for instance

man

versus

men

,

mouse

versus

mice

, the most unusual being

woman

versus

women

, whose distinction is seen in writing in the second syllable but is heard in pronunciation in the first syllable: [wɪmn] versus [wÊmn]. In German, by way of contrast, internal vowel change to distinguish singular from plural is robust. These regular vowel variations are called

Ablaut

, a term coined by Jakob Grimm.

Arabic is also organized around internal vowel changes but in a different way than the process operates/operated in Indo-European languages. You saw examples in this chapter and now in Exercise 1 of the triliteral roots, which can sometimes be biliteral and even quadriliteral. These roots can only be consonants or long vowels. They function as the fundamental lexical units around which vowels are inserted and to which prefixes and suffixes may be added to form the many pattern-templates that produce the verbal and nominal possibilities in the language. In order to look up a word in a dictionary, you have to be able to identify the root, because the âspin-offs' from the pattern-templates are listed under the root and not in strict alphabetical order. The word

maktaba

âlibrary' will not be found in the words beginning with letter âm' but under those with âk' because the root is: k-t-b âto write.' This entry will furthermore appear very near the beginning of the âk's because ât' ( ) is the third letter of the Arabic alphabet.

) is the third letter of the Arabic alphabet.

Arabic is one of the languages of the world with a long history of study and discussion, and it is because of Islam. In the East, commentary on language can be found in the sixth century BCE and the work of Lao Tsu. In the West, it starts in the fourth century BCE and Plato's

Cratylus

. In the Middle East, the first work on Arabic grammar comes in the eighth century CE and the grammarian SÄ«bawayh's great

al-Kitab

. SÄ«bawayh was not an Arab; rather he was Persian, and his observations on Arabic have stood the test of time. He is the one who first noted the pattern-templates of Arabic and started the tradition of representing them thusly:

CaCaCa or

C1aC2aC3a

This is the pattern-template for creating the past tense (masculine). If we plug in the triliteral root for âto write,' we get

kataba

âhe wrote.'

If we use the template:

maCCaC

we can produce words that mean something like âplace where,' such as

maktab

âoffice,'

madras

âschool' from d-r-s âto study, learn,'

matbax

âkitchen' from t-b-x âto prepare

food, cook,'

maghreb

âNorth Africa' from Ê-r-b âto depart, withdraw' and, by extension, âstranger' and âwest' (presumably someone coming from the west).