Languages In the World (49 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

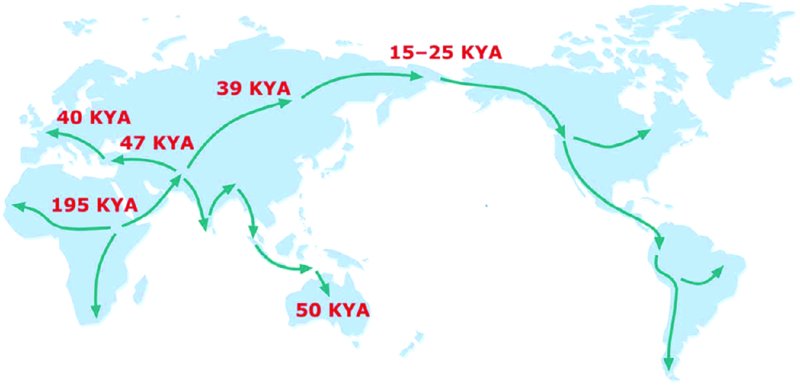

Map 10.1

Expansion of human species (

http://www.sanger.ac.uk/research/projects/human evolution/

). Reproduced by permission of Genome Research Limited.

Furthermore,

ASPM-D

, in particular, shows signs of accelerated evolution in humans, with approximately two favorable mutations per million years. In the areas of the world where the new alleles (

D

-variants) are relatively rare, tone languages are common, and both historical and geographic factors can be ruled out to explain this

negative correlation with tone and the population frequency of

ASPM-D

and

MCPH-D

. Although Dediu and Ladd acknowledge that the effects on the

D

-variants on brain structure remain largely speculative, it is nevertheless possible that the variants introduce a biasing effect with respect to the cognitive capacities involved in processing phonological structures. Dediu and Ladd (2007:10944) do not doubt that all normal children learn the languages of the community in which they are raised, but it is nevertheless worth imagining that cognitive biases in a population of language learners could influence the direction of change such that “extremely small biases at the individual level can be amplified by th[e] process of cultural transmission and become manifest at the population level.”

Whether or not Dediu and Ladd's hypothesis will survive further scrutiny is not at issue. Rather, we introduce it in order to underscore a point we would like to make in this book, namely that students of linguistics can and should be expected to have a decent grasp of linguistic geography, language family structural characteristics, typological and areal features, as well as population genetics in order to evaluate the kinds of information and hypotheses they are apt to encounter in their research. They also need a good idea about social and political linguistic effects, as well. However, for the time-depth of this chapter, the sociopolitical effects are unknown and unreconstructable, if we even wished to use a term like

political

to refer to events in a time before identifiable political structures with administrative hierarchies existed.

We turn to Johanna Nichols, once again, in our attempt to establish relationships among languages at a time-depth greater than 10,000 years where the graphic model such of the tree with its branches, the wave with its isogloss bundles, or the rhizome with its tangles cannot capture the possible relationships. Only statistical approaches and knowledge of favored and disfavored structural patterns can help fill in the blanks

of the dispersals of languages and the encounters of speaking groups. Rather than establishing individual etymologies and comparing particular grammatical structures, deep-time historical linguistics depends on typological information as the best guide to what linguistic structure may have been like at the beginning of human movements around the world.

A hardly exhaustive list of the relevant structural categories includes the following. First is the inclusive/exclusive pronoun distinction. As was noted in Chapter 7, Austronesian languages have both we-inclusive and we-exclusive first-person plural pronouns. This feature is not found in the languages of Europe. It is, however, widespread in Australia and the southern and eastern New World, the latter languages descending from the earliest colonizers. Those who came into the New World later settled in the north and west, and the occurrence of this inclusive/exclusive in North America is statistically that of the Pacific coast of Asia.

Second is the numeral classifiers. Mentioned in Chapter 2 is the fact that some languages distinguish between mass nouns and count nouns, while others treat all nouns only as mass nouns. As it turns out, noun classifier languages are strongly areal in distribution. They are concentrated in Southeast Asia, including the western Pacific, and coastal western America. The distribution of this feature is what Nichols says “can be reduced to a single circum-Pacific hotbed” (1992:133).

Third is the presence or absence of alienable versus inalienable possession, discussed in the Language Profile for Hawaiian in Chapter 7. Diegueño, indigenous to California, makes a distinction between

Ê-schwatal

y

âmy mother' (inalienable âmy'

Ê

) and

Ê-schwan

y

-schwawa

âmy house' (alienable âmy'

Ê-schwan

y

). Such a distinction is widespread in Native American languages.

Fourth is whether sentences align to the accusative type, where Subjects and Agents line up and Objects are distinct, or to the ergative type, where Subjects and Objects line up, and Agents are distinct. To remind you, the alignment distinction turns on the difference between transitive verbs and intransitive verbs. Transitive verbs are ones that can take an object: âShe bought the pig.' Intransitive verbs are ones that cannot take an object: âJohn fell.' Thus, an accusative type language is one in which the nominative case lines up with the Subject, and the accusative case lines up with the Object, no matter what kind of verb is used. The accusative type is the one readers of this book are likely most familiar with. The ergative type is found in languages like the language isolate Basque and the Caucasian language Georgian.

The ergative type is also found in Dyirbal, an Aboriginal Australian language, where the Subject of an intransitive verb (here:

to return

) is in the absolutive case:

| yabu | banaga-n y u |

| âmother' | âreturned' |

| absolutive case/zero morpheme | nonfuture |

| âthe mother returned.' |

The Subject of a transitive verb (here:

to see

) is in the ergative case:

| numa | yabu-ngu | bura-n |

| âfather' | âmother' | âsee' |

| absolutive case/zero morpheme | ergative/morpheme ngu | nonfuture |

| âthe mother saw the father.' |

Note, first, that âfather' is the Object of a transitive verb and is in the absolutive case just like the Subject of an intransitive verb and, second, that normal word order puts the Object first, making the order OSV.

Specialist in Aboriginal Australian languages, R.M.W. Dixon explains the logic of ergativity to be one of marking true agency. In the case of a sentence like âJohn fell,'

John

is in the nominative case in transitive languages. In an ergative language,

John

is in the absolutive case, because he is not seen as the agent of the action. He is treated grammatically as no different than the object of a transitive action done by someone else; he is an object not in control of the action. When it comes to John being the agent of an action, as in âJohn killed the snake,' then John is marked for ergativity (Dixon 1994:214). Despite the logic that governs ergativity, the overwhelming global pattern is for accusative alignment. Languages with ergative constructions tend to cluster geographically.

Fifth is head marking versus dependent marking; we had our first look at this structural feature at the end of Chapter 1 in the discussion of the grammatical category of possession. The distinction belongs to Johanna Nichols, and she has increased typological understanding by showing how the preference for one or the other kind of marking runs throughout the whole grammar. In the simplest definition of the terms, the head determines the possibility of the occurrence of the dependent. For instance, we can talk about a house without referring to the person who owns it, so the house is head, and the potential possessor is dependent. On page 17 we saw in the pairs of phrases from English, Spanish, and Hungarian that English and Spanish put the grammatical marking on the possessor, while Hungarian puts it on the thing possessed, the head. Furthermore, we can talk about a house without specifying what color it is. So, the house is still the head, and now the adjective is the dependent. The Indo-European languages retaining gender classes, which is all of them except Afrikaans, Bengali, English, and Persian, mark the lexical properties of the head noun on the dependent adjective. A head-marked example comes from Shuswap, spoken in British Columbia:

| wist | t- citx |

| âhigh' | âhouse' |

where the word

wist

âhigh' bears no marking, while the

t-

clitic on

citx

âhouse' marks the particular case of the noun. A dependent-marked example comes from Russian:

| zelen -yj | dom |

| âgreen' | âhouse' |

where the

yj

suffix on the adjective

zelen

âgreen' indicates the lexical properties of the house, which is singular and masculine, as well as its syntactic properties, namely that it is nominative (subject); the global preference is for head marking.

Just as the basic word-order patterns of a language harmonize with the word-order patterns of smaller units, so head-marking and dependent-marking preferences harmonize with basic word-order patterns. Nichols observes that head-marking morphology favors verb-initial order, while dependent-marking morphology disfavors it, and there seems to be a cognitiveâcommunicative reason. When the verb comes first, as it does in

head-marking languages, the grammatical relations, which are marked on the verb, are established at the outset. When the nouns come first in a language having at least some dependent-marked morphology, then the grammatical relations, which are marked on the noun, are established at the outset. Nichols concludes, “Establishing grammatical relations at the beginning must be communicatively efficacious, in that it streamlines the hearer's processing” (1986:82). When it comes to determining who did what to whom, dependent-marking languages distribute all the grammatical information onto the

who

, the

what

, and the

whom

, as we are familiar with from the Indo-European case system, and these are the dependents. Head-marking languages will put this information on the

did

, namely the verb (head) in a combination that might look like this:

the man

,

the woman

,

the book

,

it-to-her-he-gave

.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about the head/dependent-marking distinction is its stability and conservatism of morphological marking type. Even in a geographical area where there is intensive linguistic convergence such as in a residual zone, the languages gathered there may massively borrow lexical items one from the others, the phonologies of the languages may come to share many properties, and grammatical realignments may occur (including ergativity and word-order type). Plus there might be near-identity of material culture and folklore. However, in the Caucasus, for instance, the strongly head-marking Northwest Caucasian languages and the strongly dependent-marking Northeast and North Central Caucasian languages have never given up their long-term marking type (Nichols 1986:98). Thus, the preference for marking type may be one of the oldest diagnostic criteria for establishing long lineages.

From the geographic distribution of the aforementioned five structural features, we can come to a plausible conclusion that there was a west-to-east movement out of Africa and into the Near East and from there to the tropical Pacific. Northward expansion, including colonization of the New World, occurred later (Nichols 1992:259). After that, there was a counterclockwise movement from Southeast Asia north and to the west, such that all language stocks found in Western Europe today â Indo-European, Uralic, and Turkic â originated east of the Urals. As for the case of Basque, it is not known whether it is a sole surviving remnant also from the east of a pre-Indo-European spread across the Eurasian steppe or whether it is a continuant of an indigenous Cro-Magnon language. All that is known is that Latin did not completely wipe out Basque, but it did succeed in reducing it to its own stock (Nichols 1992:236).

The accumulation of large databases such as the

World Atlas of Language Structure

(Oxford, first published in 2005) has permitted historical linguists to compare structural features in order to determine the statistical regularities that suggest lineage affiliations. This database has been put to inventive use in a recent article that lines up structural features of hunter-gatherer languages and contrasts them with those of languages spoken by agriculturalists. Apart from predictable differences in vocabulary developed as part of the agricultural lifestyle, unexpected typological differences emerge, the most significant being that, among languages spoken by hunter-gatherers, there is a strong tendency not to have a dominant order of major sentence constituents, and if there is one, it is

not

SVO. It is also the case that hunter-gatherer languages prefer small vowel inventories. Finally, with regard the tripartite lexicalization of

finger

â

hand

â

arm

, it is very uncommon worldwide that no division is made among the three body parts, and it is very common worldwide that a three-way division is made. Hunter-gatherer

languages, however, prefer to distinguish

hand

from

arm

but not

hand

from

finger

. The speculation is that hunter-gatherer societies make little use of rings, thereby making the differentiation of the fingers from the hand less salient (Cysouw and Comrie 2013).