Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (25 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

A new opportunity, however, presented itself in the spring of 1917. On April 30, two important visitors arrived in Giverny for a visit: Étienne Clémentel and Albert Dalimier. Both men had been important members of Aristide Briand’s government: Clémentel as the minister of commerce and industry, Dalimier as the undersecretary of state for the fine arts. When Briand’s coalition government collapsed in the middle of March, replaced by one put together by Alexandre Ribot, both men kept their posts. There was still no place in government for Clemenceau. The British ambassador reported that the Tiger had been undermining his position with “continual but unreasoning attacks in his newspaper on Monsieur Briand and the authorities generally,” and he concluded that Clemenceau had “rendered himself impossible.”

44

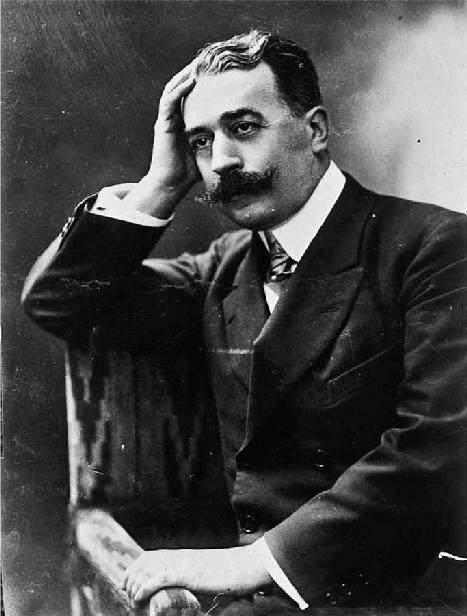

Étienne Clémentel, powerful politician and welcome visitor to Giverny

The arrival for a personal visit of two important members of the government shook Monet out of his long torpor. They were most welcome guests, combining as they did an educated and sympathetic interest in the fine arts with sweeping financial powers. Clémentel was an energetic fifty-three-year-old with a large and important ministry under his control. Indeed, the name of his cabinet portfolio—minister of commerce, industry, posts and telegraphs, maritime transport, and the merchant marine—indicated his vast powers and responsibilities. He was famously busy, pursued by secretaries with documents awaiting his signature and pages bearing visiting cards from officials and captains of industry hoping for meetings. All were forced to compete for his time and attention with each other, with his mountains of paperwork, and with his young children, on whom he doted at his house in Versailles.

45

Clémentel had long been a great supporter of the arts, in particular the Impressionists. He had even studied painting and sculpture before turning to politics. During long political meetings he often made swift pencil sketches of his colleagues, and his few periods of recreation were spent at an easel in the countryside, where he produced canvases, according to a friend, “in numbers that showed the painter’s energy to be at least as tireless as the Minister’s.”

46

He was a friend of both Renoir and Rodin, and had been the one to persuade Rodin to donate his works to France so the Hôtel Biron could be transformed into a museum. He had even been the subject of Rodin’s last work, a portrait bust that revealed him in a defiant pose: shoulders bare, chin up, moustache smartly bristling.

Clémentel and Dalimier were undoubtedly given a tour of the Grande Décoration in Monet’s studio. However impressed they may have been with these efforts, they presented him with quite a different proposition. As Monet reported on the following day to Geffroy: “I agreed to go to Reims (at least when the shells stop falling) to paint the cathedral in its present state. This interests me a lot.”

47

Monet had done his famous series of paintings of the cathedral in Rouen, and he seems to have entertained the idea, years earlier, of tackling a series of paintings of French cathedrals: one of his notes records his desire to paint “the cathedrals of France.”

48

Now the opportunity presented itself to set up his easel in front of another cathedral—a state-sponsored commission, no less, arranged for him by the government’s top cultural supremos.

Notre-Dame de Reims was not just any French cathedral. The critic Charles Morice, writing before the war started, called it “the national cathedral.”

49

Twenty-six kings and queens of France had been crowned inside the cathedral, the latest version of which, begun early in the thirteenth century, was decorated with some of the most beautiful and innovative statuary in Europe, regarded by Rodin as superior to anything done in Italy. And yet Reims and its beautiful cathedral had become victims of German artillery, an obscene testimony, in the eyes of so many in France, to the barbarism of the “Huns.” The Germans had bombarded the city for five straight days in September 1914, killing dozens of people and hitting the cathedral (which they claimed, by way of justification, was being used by artillery spotters) with more than two hundred shells. Stained-glass windows were destroyed, the roof caught fire, and a beatifically smiling angel on the façade—one of the masterpieces giving the cathedral its worldwide reputation—was decapitated, its head falling to the ground and breaking into pieces. The damage to such an important historical and religious monument gave the Allies, as a German journalist ruefully noted, “a convenient propaganda tool.”

50

To be sure, condemnation of the shelling of the cathedral had been widespread and immediate. The Académie Française denounced “the savage destruction of the noble monuments of the past,” while the Académie des Beaux-Arts raged against the destruction “inflicted

on one of the most sublime productions of French genius.”

51

A senator, Camille Pelletan, declared: “The cry of horror that has risen around the world shall be perpetual.”

52

Photographs of the architectural carnage were widely distributed, showing the façade of the cathedral wreathed in smoke and the skeletal stonework rising above piles of rubble. The volume

Les Allemands: destructeurs des cathédrales

had been hastily produced, with Reims taking a starring role. Fragments from the building—glass, stone, a melted bronze crucifix—were conducted away like holy relics. A shell-damaged pilaster was incorporated into the pedestal of Anna Hyatt’s statue of Joan of Arc, unveiled on Riverside Drive in New York in December 1915. Meanwhile, the shattered head of the smiling angel—henceforth known as

Le Sourire de Reims

(

The Smile of Reims

)—was dispatched on a tour of the United States, Canada, Argentina, and Chile.

Reims Cathedral under German bombardment, April 1917

The outrage did not stop the shelling. By the cold winter of 1917, Reims had suffered, according to one newspaper, “twenty-eight months of almost uninterrupted bombardment”; its population had shrunk from 120,000 people to 17,000.

53

In April, on the eve of Clémentel and Dalimier’s visit to Giverny, the “Martyred City” (as it became known)

suffered another heavy shelling. Thousands of projectiles and “asphyxiation bombs” pummeled the city—some 65,000 shells in the first three weeks alone.

54

The intensity was such that the remaining civilians were evacuated to Paris and Troyes. “Ah, the bandits!” fumed an article in

Le Matin

, noting that the Germans had recommenced their “abominable vandalism” of the cathedral.

55

This time the towers were damaged and the stone vaulting of the nave, left relatively unscathed in 1914, dramatically collapsed, leaving the battered structure without a roof. “The barbarians,” reported

Le Matin

on the day of Clémentel and Dalimier’s visit to Giverny, “do not seem to want to leave a stone standing.”

56

THIS, THEN, WAS

the assignment dangled before Monet: to paint the war-ravaged cathedral “in its present state” as part of the propaganda offensive against the German “barbarians.” A series of paintings of the half-destroyed cathedral, coming from the brush of Claude Monet, would announce this dreadful vandalism to the wider world in a way that no photograph could ever hope to.

Although Monet responded eagerly to the commission, it would present a number of challenges. The most serious was, of course, that unless the shells did indeed stop falling—which seemed unlikely in the spring of 1917—he might be obliged to put himself in harm’s way. A less plausible war artist would be difficult to imagine than the seventy-six-year-old Monet. A man who raged at the wind and rain as he painted in his garden was unlikely to cope well with asphyxiation bombs and collapsing rubble. Moreover, he would be obliged to travel the hundred miles from Giverny to Reims.

Weighed against these considerable difficulties were some very attractive rewards. Most important was the fact that Monet would finally be working on a state commission—something he had coveted at least since his failed attempt to secure the contract to decorate Paris’s Hôtel de Ville. In doing so, he would, moreover, be contributing to the war effort. There were, besides, certain special dispensations, a few of which he began collecting almost immediately. Barely had the two men departed than Monet wrote to Geffroy: “I’m not sure what will be the

result of the two of them as regards my automobile.”

57

At the end of 1914 the military authorities had conducted an automobile census in France, hoping to determine “the number of motor vehicles that may be used for the needs of the army.”

58

All owners had been obliged to report to their local town hall with details of the vehicles, which were ripe for requisitioning for the war effort. Monet with his fleet of vehicles was particularly at risk, and indeed in April 1917, the month of Clémentel and Dalimier’s visit, he received notice to report with one of them to Les Andelys, a town fifteen miles away. This notice was evidently presented by Monet to Clémentel for his special attention. Despite his massive workload, the minister wasted no time in intervening. One day after Clémentel’s visit to Giverny, Monet was approached by a local government official bearing the happy news “that there is no need to present my automobile at Les Andelys and that I can keep it, which gives me great joy. I thank you a thousand times for your intervention,” he wrote to Clémentel, “and also that of Monsieur Dalimier.”

59

Monet’s automobile, while off-limits to the military authorities, was no good without petrol, which was in regrettably short supply, especially since a decree of April 16 had strictly regulated consumption by members of the public: only those with “real needs” were to be provided with fuel, and then only with “the strictest economy.”

60

But a word in Clémentel’s ear was all that it took for a supply of gasoline to make its way to Giverny from a fuel depot at Vernon.

61

These were only the first of many favors that Monet would extract from the minister as—theoretically at least—he went about his war work.

THE SPRING AND

early summer of 1917 looked an unlikely time for an elderly civilian to make his way to the western front for some plein air sketching. Mutinies had broken out in the French army following the dismal failure in April of the offensive on the chemin des Dames, a few miles northwest of Reims, when massive casualties had been sustained (120,000 on April 17 alone) with no discernible gain in territory. The entire 21st Division, veterans of the atrocious combat at Verdun, refused to go into battle. Railway tracks were sabotaged to prevent

troops reaching the front. The red flag was raised and revolutionary songs sung.

In Paris, prices continued to climb as food became ever scarcer. From the middle of May, in order to conserve supplies for the soldiers, buying and selling meat was banned on Thursdays and Fridays in all shops, hotels, restaurants, canteens, and bars. Fish, complained a restaurateur, was an “impossible hypothesis.”

62

Patissiers could still make cakes with wheat flour, except on Mondays, while France’s biscuitiers, according to a decree of May 3, were forced to make their wares from rice flour—a regulation that resulted in a protest from the Committee for the Defense of French Biscuits.

63

Biscuit makers were not the only ones up in arms. May Day passed off peacefully apart from a few cries of “Long live peace!” and “Down with the war!” But the strikes began on May 11, first of all in the clothing industry and then, by June, spreading to companies making gas masks, helmets, and munitions. Soon 100,000 people in Paris were out on strike. In the middle of June, 5,000 workers at a gunpowder factory in Toulouse walked off the job, some carrying red banners and singing the “Internationale,” whose opening lines—“Stand up, prisoners of hunger!”—resonated throughout France.

64