Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (23 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Before his death in 1916, General Gallieni had been among the cast who posed for his portrait in the boulevard Berthier.

Le Gaulois

, one of the project’s numerous sponsors, announced to its readers that Carrier-Belleuse and Gorguet “inform the families they are at their disposal to create portraits of decorated heroes both dead and surviving, either from nature or from photographs, in their workshop, for the purpose of glorifying these heroes.”

53

Into the grand new building filed mourning women in black veils “crying while bringing their images, sacred relics of a dearly departed.” From these dead heroes, Carrier-Belleuse claimed, “a living one was made.”

54

There could be no shortage of these mourning women: by the time Carrier-Belleuse and Gorguet moved into their new building, French deaths were approaching one million.

Finding time in his busy schedule to stand for Carrier-Belleuse and Gorguet, with his arms crossed in a pose of steely determination, was Georges Clemenceau. He probably had scant regard for the old-fashioned artistic style of these painters, although he appears, at least, to have raised no complaints about his portrait having been botched. He was, in any case, highly sympathetic to the project of commemorating French heroism. In the autumn of 1916 he made another of his fact-finding visits to the front. Soon afterward, in November, he paid one of his regular visits to Giverny. “Clemenceau was just here,” Monet wrote to Geffroy, “and he left enthusiastic for what I have done. I told him how badly I wanted your opinion on this formidable work, which is, to tell the truth, sheer madness.”

55

Monet was eager to show his work to friends such as Clemenceau and Geffroy, and to receive their opinions and encouragement. Despite

the uncooperative weather, the problems with his teeth, and “all the anguish and worries of this war,”

56

his mood had been optimistic throughout much of the year. His greatest fear, he told Clemenceau—perhaps with the sorry fates of Mirbeau and Rodin in mind—was “never finishing this immense work.”

57

As his seventy-sixth birthday passed in November, Monet responded to good wishes from the Bernheim-Jeunes with a few lines of contented optimism: “I am happy to let you know that I am more and more passionate about my work, and that my greatest pleasure is to paint and to enjoy nature.”

58

CHAPTER NINE

A STATE OF IMPOSSIBLE ANXIETY

IN DECEMBER 1916,

Monet prepared to receive an illustrious visitor. “Regarding Monsieur Matisse,” he wrote to the Bernheim-Jeune brothers at the end of November, “you may tell him that I would be happy to receive him.” However, he wished to delay Matisse’s visit for several weeks because he needed, he said, “to add a few touches to the

grandes machines

.”

1

Many others had been given a sneak preview of the paintings, from Clemenceau and the Goncourtistes to the beautiful American socialite Gladys Deacon, who had been welcomed in Giverny in the autumn of 1914. But Monet evidently believed they needed a bit of touching up before another painter should be allowed to see them.

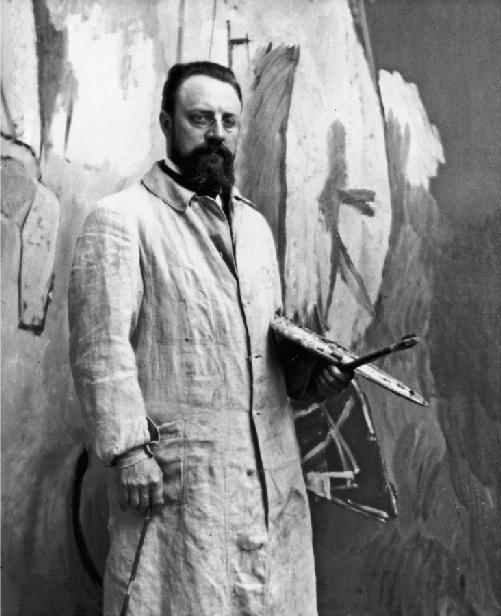

And not just any painter. Henri Matisse was prominent and successful—“one of the most robustly talented painters of the day,” according to the critic Louis Vauxcelles.

2

Over the past dozen years Matisse had gone from the leader of a shocking and controversial group of young painters dubbed the Fauves (wild beasts), whose paintings one critic attacked in 1908 as a “spectacle of unhealthy shams,”

3

to an acclaimed and respected artist who in 1910 had enjoyed a retrospective of his work at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune and a solo exhibition in New York. “From morning to night it did not empty,” Mirbeau had reported enviously to Monet on the triumph of the Bernheim-Jeune retrospective. “Russians, Germans, male and female, drooling in front of each canvas, drooling with joy and admiration, of course.”

4

At the end of 1916 Matisse was approaching his forty-seventh birthday. Dapper, bearded, and bespectacled, he looked like a professor, although he was still notorious enough for enraged art students in Chicago to have burned three of his paintings in effigy in 1913 and to have placed “Henry Hair Mattress” (as they mocked him) on trial for

“artistic murder” and “pictorial arson.”

5

He and Monet had never met. For the most part Monet paid little attention to the younger generation of painters. In 1905 he told an interviewer that he did not understand Gauguin’s painting: “I never took him seriously anyway.”

6

Matisse, however, had been Monet’s most talented artistic offspring, studying his works with the zeal of a devoted acolyte. He had first discovered Monet’s works in the mid-1890s through his friend, the Australian painter John Peter Russell, for whom Monet was “the most original painter of our century.”

7

Soon Matisse was setting up his easel in spots where Monet had once painted—before the rocks on Belle-Île-en-Mer, for example—and becoming such a dedicated admirer that, as a friend claimed, he “swears only by Claude Monet.”

8

The “robustly talented” Henri Matisse, photographed in 1913

Within a few years Matisse developed a bold new style of his own, forsaking the Impressionist palette and painting in the riots of unnatural, high-keyed colors that won him and his friends, such as André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, the nickname Fauves and the reputation as artistic

provocateurs

. Monet was, for the Fauves, a painter to learn from—and in 1905 Derain even went to London to paint the same subjects—but one ultimately to be superseded. They aimed to express something less fleeting and more substantial than what they claimed were the mere “impressions” put down on canvas by Monet. “As for Claude Monet,” Derain wrote to Vlaminck in 1906, “in spite of everything I adore him... But finally, is he right to use his fleeting and insubstantial colour to render natural impressions that are nothing more than impressions and do not endure?...Personally I would look for something else: that which on the contrary is fixed, eternal and complex.”

9

The term “Impressionism,” Matisse announced in 1908, “is not an appropriate designation for certain more recent painters”—himself and his friends—who “avoid the first impression, and consider it almost dishonest. A rapid rendering of a landscape represents only one moment of its existence.” Matisse insisted that he wanted to depict the “essential character” of the landscape rather than the “superficial existence” brushed so rapidly by the Impressionists, whose canvases, he claimed, “all look alike.” He wanted to give reality “a more lasting interpretation.”

10

His windy afternoons at the easel by the sea on Belle-Île, struggling to capture the shifting effects of light, froth, and spindrift, were, at this point, clearly a thing of the past.

Monet was undoubtedly aware of Matisse’s slighting comments, which had been published at the end of 1908 in

La Grande Revue

, a prestigious literary journal. They lie behind Mirbeau’s savage assessment of Matisse’s work in a letter to Monet in 1910: “You cannot believe such folly, such madness. Matisse is a paralytic.”

11

But by 1916 the artistically restless Matisse had revised his position, and once more he was concerned with the more delicate nuances of light and atmosphere. “I felt that this was necessary for me right now,” he told an interviewer.

12

In particular, he took a renewed interest in the work of Monet and Renoir,

asking the Bernheim-Jeune brothers and other mutual acquaintances to arrange visits with both of them.

By this time Matisse was living in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a few miles southwest of Paris, his age having prevented him from joining the army in 1914 despite his efforts to volunteer. He had begun a

grande machine

of his own, a canvas some eight and a half feet high and almost thirteen feet wide. He had started this huge work,

Bathers by a River

, in 1909, working on it sporadically as he struggled to absorb and surpass Picasso’s Cubism. He and Picasso were in the midst of an artistically productive game of tag, building on each other’s styles to create, in the early years of the war, increasingly geometrical compositions with flat, fractured, and overlapping planes, broad passages of black, and rigid, angular human-oids with only the most schematic features.

Bathers by a River

would mark one of Matisse’s closest encounters with Cubism.

13

Yet Matisse’s experimentation with a Cubist artistic vocabulary was rapidly running its course. In the summer of 1916 he showed works with Picasso at the Galerie Poiret in the rue d’Antin. The exhibition,

L’Art Moderne en France

, did not go down well with many critics, not least because Picasso elected to show

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

in public for the first time. “The Cubists are not waiting until the end of the war to reopen hostilities,” complained one critic, while another declared: “The time for tests and experiments is over.”

14

The war years were difficult for artists in general, but for the modernists—especially ones who, like Matisse and Picasso, were not wearing uniforms—they were especially so. Matisse was in a tricky position. He was closely associated with Picasso, a foreign national and known pacifist. He was promoted by German dealers in Paris such as Wilhelm Uhde and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, both of whose collections were sequestered during the war as the property of enemy aliens. His works were bought by German collectors such as Karl Ernst Osthaus, who had been active in the Pan-German League. And by experimenting with Cubism he was identifying himself with a modern style of art that during the war years was castigated in France as

boche

(kraut). In the summer of 1916, for example, an illustrated weekly called

L’Anti-Boche

featured on its cover a cartoon, done in a faux Cubist style, of Kaiser Wilhelm; the

caption screamed: “Kubism!!!”

15

Any taint of a German association was not to be taken lightly at a time when nationalism and xenophobia were such that the Académie Française was seriously debating how to eliminate the German letter

K

from the French alphabet.

It was during this period of political duress and artistic uncertainty, then, that Matisse approached Gaston and Josse Bernheim-Jeune about arranging a visit to Giverny. He may simply have been curious about Monet’s new project, word of which was percolating through artistic circles. But he was also hoping to replenish his painting by abandoning his austere Cubist-inspired “foreign” style and returning to paintings that in their concern for color and atmosphere were much closer to Impressionism, and to “Frenchness.”

16

THE HISTORIC VISIT

between Monet and Matisse failed to come off at the end of 1916. Early in December, Monet entertained the painter André Barbier, an unctuous young admirer, happily reporting to Geffroy (who arranged the visit) that he “seemed very enthusiastic about everything he saw.” He even allowed Barbier to take away “a nice souvenir of his visit”: one of his pastels.

17

But the obscure and fawning Barbier was one thing, Matisse quite another. Suddenly overcome with doubts about his paintings, Monet canceled the planned visit almost as soon as it was agreed on. “I am immersed in several changes in my large canvases,” he informed the Bernheim-Jeunes in the middle of December, “and do not go out. I’m in a foul mood.” He then added a P.S.: “If you should have occasion to see Matisse, explain to him that at the moment I’m all mixed up, and I’ll alert you as soon as I emerge from this state of anxiety.”

18