Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (27 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Whatever the case, Clémentel did little to put Monet’s mind at ease about the commission. Two months later the official commission seemed no nearer, and so once again the unresponsive Minister received an anxious letter from Giverny. “Here I am, pretty worried about your silence,” Monet wrote to him. “I know you must be overworked, but I wonder if you received my last letter. A word of response would make me happy, and I would like to reiterate that I would be delighted if you could take advantage of my modest invitation when you have a little leisure.” The modest invitation was, of course, to enjoy lunch in Giverny. The letter ended on a pleading note: “At least send a little note to tell me if you received my letter.”

16

By the end of September, the bombardment subsided enough for the king of Italy, accompanied by Raymond Poincaré, to pay a visit to Reims on a special train, and some inhabitants began moving back to

the city “despite the danger that threatens them every day.”

17

But by October regular reports headlined

REIMS BOMBARDED

reappeared in the newspapers. Monet’s plangent letter to Clémentel made no further mentions of visits to the martyred city.

ALTHOUGH THE REIMS

commission may have looked in jeopardy, it appears to have kick-started Monet’s interest in painting. By the summer of 1917 he had at last resumed work on the Grande Décoration following the long hiatus of uncertainty and despondency. Once again, work on the project began to consume him. At the end of May he had brushed aside the offer of theater tickets from Sacha Guitry, whose new play was opening at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. “Bear in mind,” he sternly informed Guitry, “that I must now work more than ever because each day I get closer to the end.”

18

In a letter to Geffroy that summer he signed himself: “Your old, very old Claude Monet.”

19

Monet was bedeviled, as usual, by the uncooperative weather—what he called

temps de chien

(weather for dogs).

20

In August he reported that he was “working with more passion than ever, though I am furious at the changes in the weather”—which by this point included, besides constant heavy rains, damagingly ferocious winds that, in Paris, caused chimneys and cornices to topple and shatter in the street.

That same month, Monet’s older brother Léon died at his home near Rouen. Léon, who had run a chemical factory, had been friendly with Camille Pissarro, whose paintings he sometimes bought, and for a time he had employed Monet’s eldest son, Jean, who had trained as a chemist in England. But the two brothers had been estranged for many years, and Monet did not attend the funeral. However, the following month he did attend another funeral, that of Edgar Degas.

Monet and Degas had likewise been estranged for many years, although alienation from the obnoxious, obstreperous Degas was nothing unusual. “What a brute he was, that Degas!” Renoir once remarked. “What a sharp tongue and what

esprit

. All his friends felt obliged to desert him in the end: I was one of the last to stand by him, but I couldn’t hold out.”

21

Monet had fallen out with the anti-Semitic Degas during the

Dreyfus Affair, though they had a reconciliation of sorts a decade later when Monet’s water lily paintings went on display in 1909. “For such an occasion,” Degas told a mutual friend, “I’m reconciled.”

22

Two years later he came to Giverny for the funeral of Alice, where he appeared as a poignant figure from another age, “groping around, almost blind.”

23

Now, animosity evidently forgotten, Monet wrote a letter of condolence to Degas’s brother René, reminiscing about their “youthful friendship and common battles” and expressing “the great admiration I have for the talent of your brother.”

24

A week after the funeral, Monet wrote to Geffroy to express his disappointment at having missed him in Paris. He also informed him of a rare event: he was going on vacation. “I have worked so hard,” he told Geffroy, “that I’m exhausted and realize that a few weeks rest is called for, so I’m off to contemplate the sea.”

25

Specifically, he was going with Blanche to his beloved Normandy coast. To the Bernheim-Jeunes he explained: “We plan to leave today via Honfleur–Le Havre and along the coast to Dieppe, an absence of 10 to 15 days. I shall be happy to see the sea again, since it’s been a long time. I need the rest because I’m tired.”

26

MONET ADORED THE

sea. He once told Geffroy: “I want always to be before the sea or on it, and when I die I want to be buried in a buoy.” Geffroy added: “This idea seemed to please him, he laughed under his breath at the thought of being locked forever in this kind of invulnerable cork dancing among the waves, braving storms, resting gently in the harmonious movements of calm weather, in the light of the sun.”

27

It is difficult to imagine Monet, with his furious rants about the

temps de chien

, bobbing calmly and passively on a tempest-tossed sea. Yet there is no doubting his attraction to the seaside, especially the Normandy coast. It had been the scene of numerous painting expeditions and family holidays, including his honeymoon at Trouville with Camille in the summer of 1870.

The Normandy coast had also been the scene of Monet’s childhood and youth. “I remained faithful to this sea before which I grew up,” he once told an interviewer.

28

The family home in the rue d’Eprémesnil in

Le Havre had been only a few hundred yards from the pebbled beach where holidaymakers scrambled from beach huts to the tide line, and from where schooners and clipper ships put into port, their masts swaying and sails billowing. Monet painted some of them in 1872, when he produced

Impression, Sunrise

. Even more momentous, a short distance away, leading along the coast and toward the cliffs, was the road that, as an adolescent, he took one day with a local painter, Eugène Boudin. After Boudin had assembled his easel on a plateau overlooking the sea, Monet watched, transfixed, as he began painting the cliffs and sky. “As

of that minute,” wrote Geffroy, “he became a painter...To him the easel, colour box, paintbrushes and canvas; to him the immensity of the sea and sky!”

29

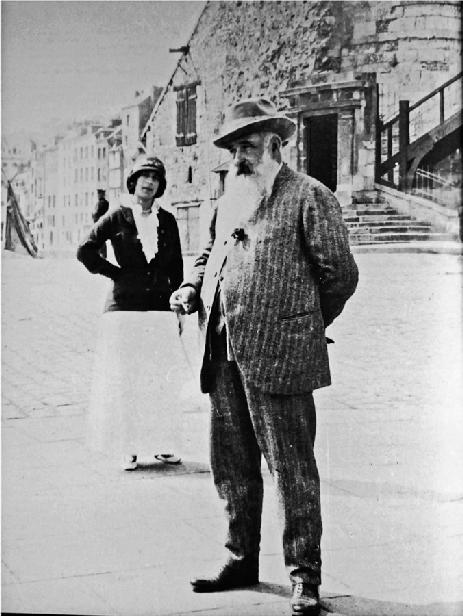

Monet on holiday in Honfleur, October 1917

On his vacation Monet stayed in both Le Havre and Honfleur. Then, blissfully unimpeded by the restrictions on petrol, he journeyed up the coast by automobile to Étretat, Fécamp, and Dieppe, places where, decades earlier, he had carried his canvases and easel along the paths both above and below the cliffs. He called it a “happy little trip,” telling Joseph Durand-Ruel that he “relived so many memories and so much work.”

30

Indeed, he could scarcely turn a corner in this part of the Normandy coast without encountering a view—a cluster of fishermen’s cottages, a contorted rock, waves breaking over strands of shingle—that he had painted at some point in the previous fifty years. But the war intruded even here along his beloved coast, with a field hospital in Étretat and, at Le Havre, a huge training camp that was preparing to receive thousands of American soldiers.

In Le Havre, Monet stayed not at the Hôtel de l’Amirauté—from one of whose windows he had painted

Impression, Sunrise

forty-five years earlier—but at another seafront hotel, the Continental. His friend Camille Pissarro had stayed at the Hôtel Continental a few months before his death in 1903, painting multiple views of the trawlers and sailboats and visiting the origins and sources of Impressionism. Monet was now making a similar journey back into the realms of his artistic youth, an expedition possibly brought about by the death of his brother Léon as well as by the fact that, like Pissarro, who did indeed die within months of his visit, he believed his days were numbered. As he had written to Sacha Guitry a few months earlier: “Each day I get closer to the end.”

But Monet was not yet ready to bob on the ocean’s eternal swell. He told Joseph Durand-Ruel that he would return to Giverny “to work with more passion still.”

31

The memories and familiar scenes, as well as the bracing sea air, clearly revived him. He was spotted beside the water by the painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, who found him “aged but handsome, stepping from a powerful motor-car and wrapped in a sumptuous fur coat...He sat on the embankment in a bitter west wind that

dishevelled his long white beard.”

32

What was Monet thinking as he sat staring out to sea? “I saw once again,” he told Georges Bernheim-Jeune, “beautiful things that stirred so many memories.”

33

MONET MAY HAVE

been revivified by something more than the bracing sea air. By the time he reached the Normandy coast he had finally heard some reassuring words from Étienne Clémentel. One of his earlier letters to Clémentel had gone astray, or so Clémentel claimed—an ironic twist, given that he was minister of posts and telegraphs in addition to his other duties. And no sooner did Monet return to Giverny at the end of October than he officially received the Reims commission courtesy of the Beaux-Arts administration. “I want to tell you,” he wrote to Albert Dalimier, “how flattered and honoured I am by this command.”

34

He was to be paid 10,000 francs for the commission.

35

This was under the going rate for a Monet. He claimed a few weeks later that his “usual price” for a canvas was 15,000 francs,

36

and the paintings auctioned earlier that year from James Sutton’s collection were hammered down for a price, on average, of more than 33,000 francs each. However, he was not undertaking the work for money, which he hardly needed: a few days later he received a check from Durand-Ruel for 51,780 francs, payment owing for sales of his works. But he knew that the commission would bring him certain things that money could not buy, such as coal, gasoline, and prestige.

Having received the commission at last, Monet’s mood brightened such that he submitted to a longstanding request from the Bernheim-Jeunes. The brothers had commissioned a biography of Monet from the critic Félix Fénéon, and they were hoping to dispatch him to Giverny for an interview. Monet finally agreed, although he asked for a couple of weeks to set his studio in order and to “rework some things that I now see with a fresh eye.” He was, however, uneasy with the idea of a biography. “For my part,” he told Georges Bernheim-Jeune, “I think it would be enough simply to deliver my paintings to the public.”

37

Monet’s reluctance shows his sincere modesty, since a biography written by Fénéon—a highly regarded art critic, gallerist,

friend of Matisse, promoter of Seurat, and editor of Rimbaud—would have been a great honor.

Monet also granted another appeal. The Durand-Ruels were still hoping to photograph some of Monet’s new paintings in order to tantalize their clients. Back in the winter, Monet had declined their request in no uncertain terms. But he was now more amenable, and so a photographer arrived in the middle of November 1917, taking a series of photographs featuring not only the massive paintings but also the grand new studio. They offered privileged glimpses of Monet’s commodious new working space. A large trestle table sat in the middle of the spartan room, the tools of the trade spread artfully across it: several jars holding dozens of brushes, a couple of palettes (one of them new), several dozen neatly stacked wooden paintboxes, and a corked bottle of wine. An old two-seater sofa faced one wall, flanked by a small end table and a wooden chair.

The real attraction of the photographs was, however, the paintings themselves, which lined the walls of the studio, riding for ease of movement on easels fitted with casters. The photographer took pictures of eight or nine canvases, ones standing more than six and a half feet high by almost fourteen feet wide. These colossal tableaux must have stunned Clémentel, Matisse, Marquet, and other visitors into an awed silence at the scale of the old man’s vast ambitions and the scope of his abilities. Two of them showed weeping willows beside the pond, their thick trunks flanked by cascading curtains of branches; others showed the blurry, reflective surface of the water lily pond. All of them attested to his vigorous efforts and immense vision—and to the truth of his claims about having used up great quantities of pigment.

The photographs also hinted at the grounds of some of his anxieties about his work. Several of them show how he placed the canvases together at angles of perhaps 160 degrees. Two of the photographs reveal four of the fourteen-foot-wide canvases positioned end to end to create an immense, curving tableau, almost fifty-six feet in length, that would take its place, if all went well, in a large, circular room.