Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (53 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Blanche was still hoping that Monet would go back to work, but Clemenceau knew that the painter’s work was finished and the end fast approaching. During the summer, Monet began coughing up blood. After he was X-rayed at a surgery in Bonnières, doctors were summoned from Paris, including Clemenceau’s physician, Dr. Florand (“all of whose patients,” the Tiger once dryly observed, “die cured”).

46

Monet was given a diagnosis of pulmonary sclerosis, but “he will never know his true illness,” Clemenceau wrote. “This isn’t necessary.”

47

In fact, the radiological exam had revealed lung cancer. The only thing that remained,

Clemenceau knew, was to keep his friend’s spirits high. “What more could one ask for?” he wrote to him in September. “You’ve had the best life that a man could dream of. There’s an art to leaving as well as to entering.”

48

Or, as he had commanded him a few weeks earlier: “Stand up straight, lift your head and send your slipper to the stars. There is nothing like doing it well.”

49

MONET DIED AT

noon on a Sunday, December 5. The hour was an appropriate one for his quietus. Sunday lunches had always been precious to him: a time when a bell summoned him from the water lilies to his lunch, where a glass of homemade plum brandy would be waiting on the terrace or in the yellow dining room, along with any guests who had been lucky enough to receive an invitation.

“You shall die before the easel,” Clemenceau once wrote to him, “and the devil take me if, arriving in heaven, I don’t find you with a brush in your hand.”

50

In the event, Monet died in his bedroom, in the “museum of his admired companions,” surrounded by the works of Manet, Degas, Pissarro, Renoir, and Cézanne. He died surrounded by other companions, too: his son Michel, the devoted Blanche, and Clemenceau, who for the previous few days had been poised to come from Paris at short notice, and who arrived on the morning of the fifth—supposedly barking at his chauffeur “Faster! Faster! Faster!”—on time to take his friend’s hand. “Are you in pain?” Clemenceau asked. “No,” replied Monet in a barely audible voice, and a few moments later, with a soft groan, he passed away.

51

That afternoon telegrams were sent to the newspapers stating that the painter Claude Monet had died at noon at his property at Giverny at the age of eighty-six, with Georges Clemenceau at his side.

On the following day, Monet’s death featured on the front page of all of the newspapers, which variously extolled him as the “Prince of Light” and the “true father of Impressionism.” They recapped his glorious career, covering his trajectory from the withering early reviews and the legendary winter spent eating nothing but potatoes, to his acclaim, as

Le Figaro

put it, as “the most illustrious representative of the

Impressionists.” In

Le Temps

, Thiébault-Sisson called him

le vieux lutteur

—the old wrestler—and noted that much of his long life had been “nothing but a fight” as he pushed painting to its limits. In

Le Gaulois

, the faithful Louis Gillet waxed poetical: “Weep, O water lilies, the master is no more who came to find upon the waves, among reflections of sky and water, the figure of life’s eternal dream.”

The funeral was conducted on December 8, at 10:30 on a hushed and misty morning. It was such a day as Monet had once loved to paint. As the correspondent for

Le Figaro

observed: “Normandy was dressed as her painter would have wished. In the still waters of the river vibrated the thousands of glitters of gold, pink and purple from which he had made his palette. The waters reflected a mysterious sky of pink, purple and gold, dissolving poplars, and the misty outlines of low hills. Normandy was a Monet.”

52

Flowers, however, were conspicuously lacking. Monet wanted no flowers or wreaths at his funeral, supposedly having claimed it would be “a sacrilege to plunder the flowers of my garden for an occasion such as this”

53

—although the pickings would have been slim, in any case, in the first week of December. Touchingly, the local schoolchildren wished to lay flowers on the coffin as a tribute to “the departed artist,” but Monet’s wishes were respected to the letter.

54

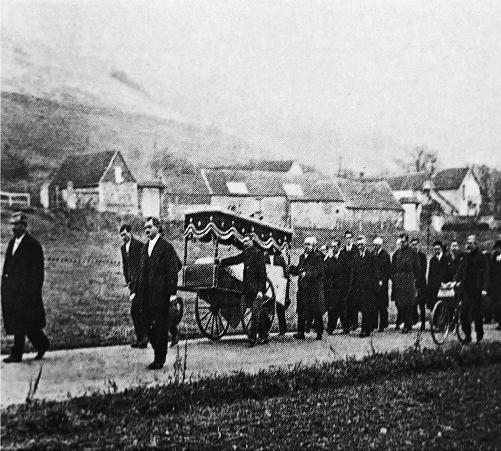

Automobile after automobile loomed out of the Givernian mist that morning, conducting friends from Paris. The procession along the narrow road from the house to the church was led by the mayor of Giverny. The maplewood coffin was borne on a small handcart with a fringed canopy decorated with stars. Two of Monet’s gardeners pulled the cart while a pair of others pushed from behind, “using the same gestures,” as one correspondent observed, “with which they carried out their daily chores.”

55

All of them were dressed, as Monet had commanded, in their work clothes. The coffin was draped with a violet cloth decorated in a floral pattern of forget-me-nots, periwinkles, and hydrangeas. The undertaker had been about to cover it with the traditional black cloth when Clemenceau intervened and protested, going to the window and tearing down the floral-patterned curtain. “No black for Monet,” he said in a quiet voice, shrouding the coffin himself.

56

Monet’s funeral procession, December 8, 1926

Clemenceau had been angered by the crush of journalists, photographers, and curious onlookers outside Monet’s house, a reaction put down by one of the interlopers to the intensity of his grief.

57

Too exhausted, grief stricken, or harassed to walk the half mile to Sainte-Radegonde, he followed the creaking procession in his chauffeur-driven automobile. Outside the church, leaning on a cane, tears in his eyes and hands trembling, he joined the other mourners. Blanche and the other women were veiled in crêpe. The men bowed their hatless heads as they gathered around the rectangle of freshly turned earth. A few handshakes and muted greetings were exchanged. Monet had asked for a civil service, so no priest was present, and no prayers were said or

hymns sung. “How much more beautiful is silence,” as Clemenceau had once observed.

58

He was buried next to his beloved Alice, his two stepdaughters, and his son Jean.

As befit a man who detested crowds and ceremonies, it was all over very quickly. After the family departed, Clemenceau stayed to watch as the coffin was lowered by the gravediggers into the ground. “Soon the graveyard was deserted,” reported a journalist. “Silence and mist wrapped for the first time the man whose brushes had so often told the poignant struggle of light and shadow.”

59

TWO WEEKS LATER,

another solemn ceremony took place in Giverny. This one, carried out in the absence of journalists and onlookers, was presided over by Paul Léon, two curators from the Musées Nationaux, and the architect Camille Lefèvre. Twenty-two of Monet’s enormous canvases were removed from the grand atelier. They were rolled up and transported to Paris to be photographed in the Louvre before being taken to the Orangerie. There, along the swoop of walls, they would be carefully unspooled: almost ninety meters, or almost three hundred feet, of painting. The work of a colossus.

EPILOGUE

THE PRINCE OF LIGHT

IN THE MIDDLE

of May in 1927, a journalist named Gaëtan Sanvoisin arrived in the rue Franklin to interview Georges Clemenceau. He was greeted at the door by a maid in a traditional laced cap from the Vendée who conducted him into a small study. In the center of the room sat a horseshoe-shaped table almost every inch of whose surface was piled with bundles of papers and pyramids of books, among which Sanvoisin spied Winston Churchill’s

The World Crisis

. Above the mantelpiece hung several sketches by Impressionist painters.

“Monsieur le Président,” Sanvoisin greeted Clemenceau when his host finally appeared in the study wearing gray suede gloves and a curious policeman’s hat, also gray, that reminded Sanvoisin of a Tartar’s helmet. “Do you wish to talk to me about Monet?”

1

The “Salon Monet” had finally been inaugurated one day earlier in the two rooms in the Orangerie. Clemenceau had been present for the occasion in the company of Blanche and Michel. “The Monets created the greatest effect,” he had written to a friend. “It’s a new kind of painting.”

2

But to Sanvoisin he was more guarded, informing him that he did not want to speak about Monet, having little desire to put his thoughts and opinions on art before the public. He was easily enticed into revelation, however, and for the next few minutes he regaled his visitor with tales of how he had known Monet in the days when he was too poor to buy pigments, how buyers who spurned Monet’s early works were later eager to part with huge sums for them, and how Monet had not wanted to relinquish his Grande Décoration until he was dead, because only at that point would he be able to bear their imperfections.

Mention of imperfections sparked a memory in the mind of Sanvoisin, who had also attended the opening at the Orangerie. “Did

you notice, Monsieur le Président,” he inquired, “that one of the canvases bears a long gash?” Indeed, several visitors to the first room had noticed a distinctive scar on the rightmost section of

Morning

, one of the canvases in the first of the two oval rooms.

Clemenceau at the opening of the Monet galleries at the Orangerie, May 1927

“A slash from his knife,” replied Clemenceau. “Monet attacked his canvases when he was angry. And his anger was born of a dissatisfaction with his work. He was his own greatest critic!” He explained that Monet had destroyed more than five hundred canvases in his quest for perfection.

“There are those, Monsieur le Président, who fear that these works will not stand the test of time.”

Clemenceau studied Sanvoisin, suddenly forlorn. “Perhaps,” he replied. He went on to explain that Monet had used the most expensive

materials, but that he could not vouch for their quality, and anyway, no painting could withstand the depredations of time. “I went to the Louvre yesterday and saw the

Mona Lisa

again. She has changed a lot in fifty years.”

Sanvoisin was voicing the fears of one of the curators at the Luxembourg Museum who a few months earlier had speculated that Monet’s “hastily applied colours,” blended in “dangerous mixtures,” might be difficult to preserve.

3

In fact, there was little reason to fret about Monet’s canvases. Despite their gossamer appearance, his paintings were not painted with “dew and the powder of butterfly wings,” as the curator joked, but with tried-and-trusted pigments that Monet—a man obsessed with “the chemical evolution of colors”

4

—bought from specialist suppliers.