Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (107 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

A fortress devoid of towers

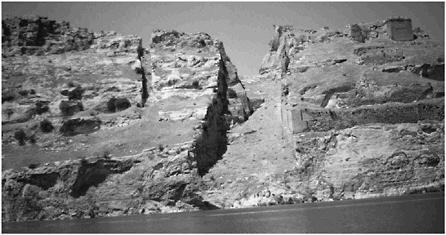

The fortress rises 76m above the Euphrates. This in itself provided ample protection. is rectangular in shape, measuring 230m from north to south and 120m from east to west. The walls follow the contour of the spur and the slopes were hewn and made vertical, as at al-Bīra. This made scaling almost impossible, although the Mamluks eventually were left with no alternative but to climb the walls. On the south, a 30m wide dry moat was dug out of the bed rock (

is rectangular in shape, measuring 230m from north to south and 120m from east to west. The walls follow the contour of the spur and the slopes were hewn and made vertical, as at al-Bīra. This made scaling almost impossible, although the Mamluks eventually were left with no alternative but to climb the walls. On the south, a 30m wide dry moat was dug out of the bed rock (

Figure 4.44

). The high and forbidding setting makes it difficult to understand where al-Ashraf Khalīl placed his 20 siege machines, and where his sappers dug or hacked a tunnel.

261

The towers that are one of the most common features of thirteenth-century fortifications and a Mamluk trademark are almost absent at . The only towers standing today are the gate towers on the west and a single tower at the southwest. The dominant features along the northern and eastern sides are the galleries. Since the western side was well protected by the steep cliff the curtain wall was of no great width.

. The only towers standing today are the gate towers on the west and a single tower at the southwest. The dominant features along the northern and eastern sides are the galleries. Since the western side was well protected by the steep cliff the curtain wall was of no great width.

In most cases the Mamluks restored and added new buildings along the circumference or within a fortress as they saw fit. At they seem to have followed the original plan, not adding but merely strengthening and repairing the existing structures, putting their faith in the sheer height and steepness of the location.

they seem to have followed the original plan, not adding but merely strengthening and repairing the existing structures, putting their faith in the sheer height and steepness of the location.

Figure 4.44 , southern moat

, southern moat

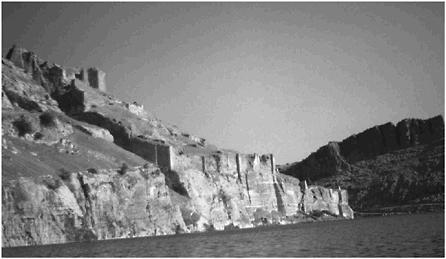

Figure 4.45 , the zigzag wall on the east

, the zigzag wall on the east

Before describing the galleries here, it is noteworthy that the curtain walls do not run in a continuous straight line, but rather short sections protrude zigzagging from the line. This reduces the dead ground below the fortress walls in much the same way as towers would (

Figure 4.45

).

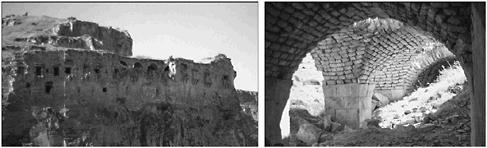

Archers’ galleries are built along the edge of the cliffs (

Figure 4.46

) they have two levels of cross-vaulted halls (3.5m in width and approximately 55m in length), built of smooth ashlars cut from the local soft limestone. The stone is neatly hewn and well dressed; no traces of mortar are visible.

The galleries were originally built by the Armenians and were designed to accommodate a large number of archers. Mamluk repairs can be identified by the different

Figure 4.46 , archers’ galleries and vaulted hall. Note the dense line of machicoulis

, archers’ galleries and vaulted hall. Note the dense line of machicoulis

design of arrow slit, which is spacious, with a large chamber in front. The smaller type is similar to those found in Armenian fortresses, where the arrow slits have no chamber and the angle of fire is narrower (

Figure 4.47

).

262

The Mamluks made several repairs, but where there was no damage they made do with the Armenian architecture.

Returning to this peculiar plan where towers are scarce, it seems that this was partly compensated by a dense line of machicolations; thus archers were able to fire down in a vertical line and defend the foot of the cliffs and walls from anyone attempting to scale them. The use of machicolations in this manner is not very common. One of the few remaining examples can be seen at Crac des Chevaliers where the gateway in the east is protected from above by numerous machicolations.

263

Otherwise they were often built directly above gates as in or Aleppo.

or Aleppo.

Multiple gates

had only one main entrance. The postern, on the east, was a steep and narrow staircase carved into the side of the cliff, and could only be used by individuals on foot (

had only one main entrance. The postern, on the east, was a steep and narrow staircase carved into the side of the cliff, and could only be used by individuals on foot (

Figure 4.48

). Once you arrived at the top you entered a gate-tower and were forced to take two sharp turns and maneuver via a narrow corridor before you entered the fortress grounds.