Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (29 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

Contrary to Crusader work, it seems at times as if more effort and thought were invested by the Ayyubids in the construction of a moat than in that of the curtain wall. In all four fortresses in this study, the moats were hewn out of the rock as opposed to being dug out of the earth and supported by counterscarps. They are all

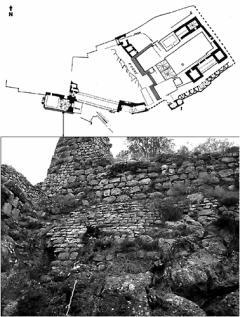

Figure 1.6 , the glacis below the southeastern gate

, the glacis below the southeastern gate

dry moats, which was more often than not the rule in the Middle East throughout history.

At , the moat exists only where the angle of the slope makes it relatively easy to access the foot of the wall. The wall itself was built after a vertical man-made cliff was hewn from the natural rock. At certain points the actual foundations of the

, the moat exists only where the angle of the slope makes it relatively easy to access the foot of the wall. The wall itself was built after a vertical man-made cliff was hewn from the natural rock. At certain points the actual foundations of the

curtain wall were laid as high as 11m above the moat. The width of the moat varies from 3 to 7.5m.

155

Mount Tabor has the most impressive of all the moats in this particular group, being of great length, breadth and depth. The moat surrounds the fortress on three sides, leaving the northern stretch of curtain wall to be protected by a fairly steep slope. It is hewn from the bedrock but, unlike the precise and neat work at , the inner side of the moat is not squared off. Because of the porous and relatively soft nature of the rock, the inner side of the moat, where the rock shows signs of cracking and crumbling, was faced with stone building blocks in order to prevent further deterioration.

, the inner side of the moat is not squared off. Because of the porous and relatively soft nature of the rock, the inner side of the moat, where the rock shows signs of cracking and crumbling, was faced with stone building blocks in order to prevent further deterioration.

is the only fortress that is surrounded by a moat from all sides. This appears to have been the only way to safeguard the site. On the southern side the moat is built up and supported by a counterscarp. The width and depth are truly forbidding: at certain points the depth reaches 8m and the width 10–15m. As the fortress was enlarged the earlier sections of the moat were built on and turned into cellars and storerooms.

is the only fortress that is surrounded by a moat from all sides. This appears to have been the only way to safeguard the site. On the southern side the moat is built up and supported by a counterscarp. The width and depth are truly forbidding: at certain points the depth reaches 8m and the width 10–15m. As the fortress was enlarged the earlier sections of the moat were built on and turned into cellars and storerooms.

156

Considering the size of the moats surveyed here, it is quite obvious that filling the moat or tunneling underneath it was not an easy task. Filling in a moat of such dimensions as at Mount Tabor, and even

and even would delay most enemy armies for a considerable length of time. The only attempt made y an army to fill a moat of a Muslim fortress occurred much later, during one of the early sieges conducted by the Mongol-Īlkhānid army against the fortress of al-Bīra (located on the upper Euphrates), in the winter of 1264–65.

would delay most enemy armies for a considerable length of time. The only attempt made y an army to fill a moat of a Muslim fortress occurred much later, during one of the early sieges conducted by the Mongol-Īlkhānid army against the fortress of al-Bīra (located on the upper Euphrates), in the winter of 1264–65.

157

Gates

The main gate is one of the few parts of the outer defenses whose structure exceeds the bounds of military architecture and partly enters the realm where aesthetics, symmetry and design play a role similar to that of monumental public buildings in urban locations. As well as the practical side of the matter at hand the defense of the entrance no doubt also had a psychological effect. Thee would often be a large inscription commemorating the ruler who had constructed the fortress. Occasionally this was accompanied by his royal emblem. The façade was clearly meant to inspire any passing travelers, neighboring inhabitants, local troops and the enemy, with respect, awe and fear. Yet gates had to be practical, allowing the passage of loaded carts, beasts of burden, men and their mounts as well as provide defense.

With regard to defense, gates mark both the most fortified and most vulnerable part of many fortresses; being a break in the curtain wall and situated at ground level they were often the obvious focal point of an assault.

As the doors were made of wood, the gate’s thickness, height and width were necessarily restricted. Being of inflammable material and lacking the strength of solid stone, wooden gates had to be concealed from the enemy’s siege machines, fire bolts and battering rams. The vulnerability of the material led to a number of creative ideas. On the whole, however, the Ayyubids followed ideas that were well established, and did not design new models of gate complexes.

A number of smaller entrances were built in accordance with the size and particular surroundings of each fortress. Some of the posterns, essentially designed as possible escape routes in an emergency, or as exit points for sorties, are located along the strongest and best protected section of the wall; some seem to have had no road or path that told of their existence.

The most common structure found among the main gates is that of the “bent entrance,” which made the passage into the fortress more defensible. It was meant to slow down and delay the enemy, giving the defenders a chance to halt a charge. The bent gate appears in various forms and has no strict dimensions. Nevertheless it is interesting to follow its development in this group of fortresses and note the advantages and weaknesses of each form (

Figure 1.7

).

The gate at was located on the northeastern stretch of the curtain wall. At the foot of one of the round towers is a bluff doorway to a non-extant passage.

was located on the northeastern stretch of the curtain wall. At the foot of one of the round towers is a bluff doorway to a non-extant passage.

158

The main gate is therefore the only entrance into the fortress. This almost seems to be the rule in small fortresses, and can be seen at both and the first phase built at

and the first phase built at . Although this gate is not built on a grand scale it requires friend or foe to take three sharp turns, each built on a different plane. An inscription commemorating

. Although this gate is not built on a grand scale it requires friend or foe to take three sharp turns, each built on a different plane. An inscription commemorating al-Dīn’s construction of the gate and the two adjacent towers in 583/1187 was placed above the entrance, decorated with a round shield crossed by a sword. Directly below the shield is a six-pointed star.

al-Dīn’s construction of the gate and the two adjacent towers in 583/1187 was placed above the entrance, decorated with a round shield crossed by a sword. Directly below the shield is a six-pointed star.

159