Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (28 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

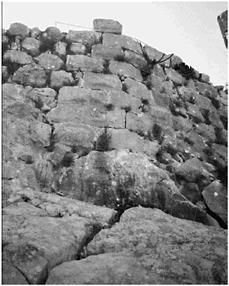

Figure 1.4 , curtain wall between towers 7 and 8 belonging to the second phase (1184–1214)

, curtain wall between towers 7 and 8 belonging to the second phase (1184–1214)

, Mount Tabor and

, Mount Tabor and follow suit. The external masonry of the towers is of a relatively higher quality than that found on the internal face of the tower and the curtain walls. However, Ayyubid masonry appears to be of a rather poor quality when one compares it to the symmetrical building blocks and high

follow suit. The external masonry of the towers is of a relatively higher quality than that found on the internal face of the tower and the curtain walls. However, Ayyubid masonry appears to be of a rather poor quality when one compares it to the symmetrical building blocks and high

quality masonry used from the second half of the twelfth century in Crusader, and later in Mamluk fortifications.

Crusader masonry is mostly defined by thin fine-combed diagonal lines, stones with marginal drafting and mason’s marks carved into the face of the stone.

147

It is hard to give a similar definition of Ayyubid masonry. The tools used y the masons did not leave any particular mark; there is no clear repetitive direction of strokes, and no masons’ marks.

Nevertheless, one can distinguish three different types of masonry.

Roughly hewn stones were used mainly for the construction of curtain walls. Marginal drafted stones are used in towers and sections along the curtain wall where the wall makes a sharp angle; this simply strengthened the structure (

Figure 1.5

). Arrow slits, main gates and minor entrances were usually built of smooth ashlar, which enables more accuracy in construction.

The stones are often tapered, in order to give the stone better anchorage in the core of the wall.

148

On the exterior, the protruding boss of the marginal drafted stones may have helped to absorb the initial shock from stone projectiles hurled from siege machines.

149

At the citadel of Arsūf small craters can be seen along the wall where Mamluk catapult stones hit the wall during the siege of 1265. The outer surface of this curtain wall, built of plain smooth ashlar was evidently not suited to absorb the shock of a strong direct attack.

150

The size of the stones is of considerable importance. When stones weighed close to a ton or over a couple of tons, loading, transporting and maneuvering slowed the progress of work. However, there are some convincing reasons as to why large-scale stones were preferred. Large stones were more durable when battering rams or siege machines were used to breach the walls. They ere also no doubt harder to force out by sappers aiming to undermine the curtain walls or towers.

Figure 1.5

An angle along the northern wall at strengthened by masonry of higher quality

strengthened by masonry of higher quality

One of the most striking exceptions is in the size of the stones used to construct the quoin of the southern tower at . The corner stones of this tower measure two and a half meters in length.

. The corner stones of this tower measure two and a half meters in length.

151

Such measurements are rare in both Crusader and Mamluk fortifications.

The first line of defense: moats and glacis

The fortresses’ first built line of defense, after the steep ravines and natural cliffs, was the moat or the glacis. In some fortresses a combination of both was employed in order to protect the curtain wall from any of the methods of assault the enemy might choose. The first and most frequent method employed by sappers was undermining walls or towers. Tunnels were dug under the foundations, stacked with wood and set on fire. Moats as well as glacis also made the use of scaling ladders difficult, as they could not be propped directly against the wall. At the siege of Mount Tabor (winter 1217) the only point where the Franks used a scaling ladder was the main gate. Maneuvering with wooden siege towers, a method the Franks often employed in the first Crusade and during the first decades of the twelfth century,

142

was made almost impossible as the moat first had to be filled in order to bring the siege tower as close as possible to the fortress wall.

The glacis was a fie swept zone surrounding the entire perimeter of the fortress or certain sections.

153

The advantages of a moat, a glacis, or both are thus obvious. It seems, however, that the better alternative as far as the Ayyubids were concerned was to defend the curtain walls by means of a natural cliff or a man-made cliff, as this provided adequate protection, was fairly cheap, and consumed little or no time if the cliff was simply part of the natural terrain.

In most cases moats were not a matter of choice; they were clearly a necessity if the fortress walls were weak and poorly built and if the natural terrain did not provide sufficient protection. is the only exception in this group. The shot moat hacked out along the western stretch of the first stage (1228) was rendered useless once the fortress was enlarged and covered the whole length of the spur.

is the only exception in this group. The shot moat hacked out along the western stretch of the first stage (1228) was rendered useless once the fortress was enlarged and covered the whole length of the spur.

154

While all four fortresses had moats, glacis are rather scarce. They ere constructed along very short stretches, below particular sections that were obviously more vulnerable than others, and needed extra protection either because the natural bedrock was not sufficiently deep, making sapping easier, or because of the moderate terrain at the foot of the wall. An interesting improvisation can be seen at where the natural rock was simply hewn at an angle, thus creating a glacis from the bedrock. At

where the natural rock was simply hewn at an angle, thus creating a glacis from the bedrock. At a glacis was laid out only below the gate-tower in the southeast. It is built of small, roughly cut stones. In certain parts they are tightly interwoven with the natural rock (

a glacis was laid out only below the gate-tower in the southeast. It is built of small, roughly cut stones. In certain parts they are tightly interwoven with the natural rock (

Figure 1.6

). It may have been a structural necessity, a wall support rather than a defense against enemy sapping.