Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (27 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

One of the few attempts to follow the precise order of building was made during the excavations of the Crusader fortress at Vadum Iacob. The excavation showed that the site had still been under construction and the fortress was never completed. This enabled the study of the order of building and the length of time required to construct certain sections of the fortress.

140

A similar exercise can be carried out at the fortress of Mount Tabor by following the dates given on the inscriptions, which state what exactly was built and when the work began or when it was completed. This may help reconstruct not only the order of building but also the time schedule. The fact that the fotress was built by the Ayyubids during a relatively short period, and was only occupied once again by the Hospitallers in 1255, for a few years before Baybars conquered it (1263),

141

allows us to follow the process with reasonable accuracy (

Table 1.1

).

The construction of the fortress lasted almost four years. It began with the building of the

bāshūra

. This immediately poses a problem as the word

bāshūra

can mean any of the following: barbican, bastion or gate.

142

The only aspect common to the thee is that they are all part of the outer defense of the fortress. It seems, however, that as the inscription commemorating the building of the

bāshūra

was found in front of the gate tower it probably refers to the building of the main gate.

143

The reservoir is dated the same year as the

bāshūra

. As there is no natural source of water at the summit it clearly received priority. Even if the reservoir constructed by the monasteries was still functioning, an additional reservoir was necessary. The

manzil

was built during the following year. The term probably refers to the living quarters. Their exact location, however, can no longer be determined. During the same year, the third year of building, the warehouse (

makhzan

) was constructed. This must have been fairly large as we are told that when the fortress was evacuated and destroyed the military supplies were distributed among , Jerusalem, Karak and Damascus.

, Jerusalem, Karak and Damascus.

144

The most puzzling element in this account is the curtain wall, which was the last important

Table 1.1

Mount Tabor: construction dates of sections of the fortress

Dates | Individual buildings in the fortress |

5th of Dhū | Foundation date of the fortress |

5th of | Bāshūra |

610/1213–14 | The building of the pool/reservoir |

611/1214–15 | Living quarters ( |

611/1214–15 | Storerooms ( |

| The building of the curtain wall |

building project to be mentioned in the inscriptions. This is somewhat difficult to explain, since a large percentage of the inner buildings in many fortresses “use” the inner face of the curtain wall as a prominent part of their structure. Vaulted galleries running along the inside of the curtain walls, towers and barracks are all constructed and supported by the curtain wall. From the defense point of view, one would assume that when undertaking such a project in a hostile country the army and the building force employed on the site would feel more secure if they surrounded themselves with a wall.

Judging from the information provided by the inscriptions it appears that the inner part of the fortress was given priority. The curtain wall was apparently the final addition. This is very different from what we know of the Crusader fortress at Vadum Iacob (1178–9), where the curtain wall was built first, allowing the large vaulted halls to be supported by it. One way of explaining the curtain wall construction at Mount Tabor is by assuming that the year given (612/1215–16) represents the date of its completion, not commencement, although the inscription does not explicitly say so.

The anatomy of Ayyubid fotresses

Turning to the individual elements that comprise a fortress, it is probably best to work from the outer parts of the defense to the center of the fortress.

Types of masonry

Determining the chronology or creating a typological chart according to masonry is a tricky matter. It demands a certain amount of caution and a survey of a much larger number of fortresses. As all four of our fortresses are dated precisely by inscriptions found on the site, the aim here is to provide a few clear descriptions of Ayyubid masonry types, and compare the findings to masonry styles employed by the Franks and later by the Mamluks.

In the introduction to

The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia

, Edwards gives this subject of masonry a great deal of thought. His ideas and advice are important and relevant to anyone working in the field. The four fortresses presented in this study all show different types of masonry, in other words, there is no uniformity. This could be due to a combination of factors. Different kinds of rock are carved in different methods. Certain regions may have had their own local style and traditions of masonry work; or, if restricted in time and funds, the architect may have decided to compromise and make do with coarsely cut and dressed stone.

145

The rusticated style at was, according to Johns, common in the region after the Roman period.

was, according to Johns, common in the region after the Roman period.

146

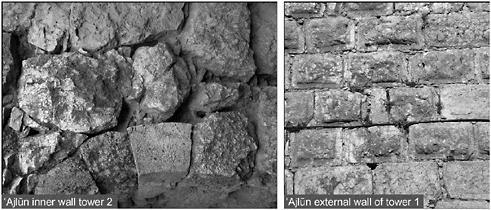

The first Ayyubid construction phase, dated 1184, used crudely cut stones. However, there is some variation. The outer face of the towers is of better quality stones than the inner face and the curtain walls (

Figure 1.3

). In the second phase, built between 1184 and 1214, the masonry is of a slightly higher standard. Both the curtain wall and the towers themselves are a mixture of ashlar and marginal drafted stone blocks of a fairly even size, cut and dressed with greater care and precision (

Figure 1.4

).

Figure 1.3 , masonry in towers built during the first phase (1184). Curtain wall between towers 1 and 2

, masonry in towers built during the first phase (1184). Curtain wall between towers 1 and 2