Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (83 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

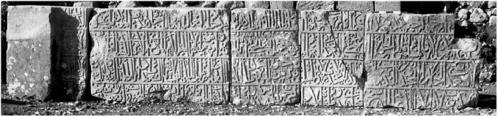

In this particular case of , the architect is not only acknowledged but is given an honorable place in the large inscription that adorned the fortress walls.

, the architect is not only acknowledged but is given an honorable place in the large inscription that adorned the fortress walls.

Figure 4.2 , the monumental inscription from the reign of Baybars

, the monumental inscription from the reign of Baybars

The fact that the term

ustādh

(master) precedes that of

muhandis

is significant: “this title (i.e

ustādh

) could not have meant more than ‘qualified builder’ or ‘foreman’. But inscriptions prove that its application was not haphazard. Certain architects are called masters from a given date onward, thus proving they were not entitled to it before.”

73

As to the origins of (

(

al-ustādh

,

al-muhandis

) and

no clue is given, nothing is known of them or their previous works. They may well have been brought from Egypt or Syria or from beyond the Sultanate’s borders: “architecture has always been an international craft and medieval architects moved to where there was most to be built and where patronage could be expected.”

no clue is given, nothing is known of them or their previous works. They may well have been brought from Egypt or Syria or from beyond the Sultanate’s borders: “architecture has always been an international craft and medieval architects moved to where there was most to be built and where patronage could be expected.”

74

It is interesting to compare the respective ranks of the teams that dealt with the building of fortresses in the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods. The Mamluk supervisors were evidently of a higher rank than the team that oversaw the last Ayyubid building phase (1239–40). The Ayyubid construction work was supervised by a eunuch who was a great amir (

al-amīr al-kabīr

). His name appears before that of the governor of the fortress. Compared to the Mamluk

nā’ib

, his responsibilities were fewer and less demanding. The Mamluk

nā’ib

, Baktūt, not only commanded the fortress, but also administrated the lands that belonged to his master and commanded Bīlīk’s cavalry unit which was permanently stationed in Damascus.

75

Baktūt too was given the title of great amir. Humphreys has a lengthy discussion on the title “

al-amīr al-kabīr

” in which he concludes that while the Ayyubids used the title very loosely, during the Mamluk period it was generally equivalent to the rank of amir of a hundred horsemen (

amīr mi’a

).

76

The Mamluks appointed officers of higher rank simply because belonged to the

belonged to the and the fortress was accordingly staffed with amirs from his own body of Mamluks, who belonged to a higher class.

and the fortress was accordingly staffed with amirs from his own body of Mamluks, who belonged to a higher class.

Table 4.1

The rank of the building teams according to the inscriptions at

Ayyubid | Mamluk |

| Baybars (sultan) |

↓ | ↓ |

| Bīlīk (na’ib al-sultana) |

↓ | ↓ |

Mubāriz al-Dīn (Mamluk amir [?], governor) | Baktuk (Mamluk amīr kabīr, governor of the fortress) |

| ↓ |

| Sanjar (an amir) |

| ↓ |

|

|

| ↓ |

|

|

| ↓ |

| Yusuf (inscription writer) |

Note: The Ayyubid order follows an inscription of 1239–40; the Mamluk order goes according to the inscription of 1275 |