Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (86 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

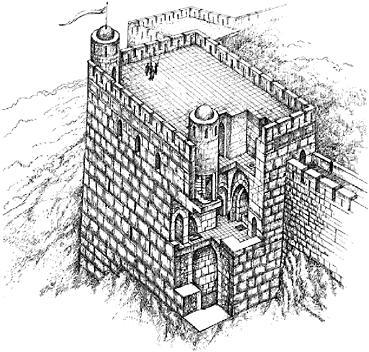

Figure 4.11 reconstruction of tower 11 (Bilik’s tower)

reconstruction of tower 11 (Bilik’s tower)

Figure 4.12 , secret postern in tower 16 leading to the core of the Ayyubid “keep” and the grand Mamluk hall

, secret postern in tower 16 leading to the core of the Ayyubid “keep” and the grand Mamluk hall

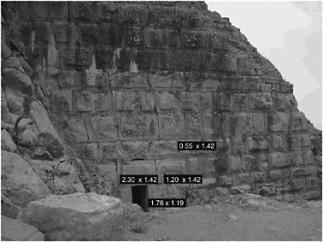

Figure 4.13 , giant stones along the northern face of tower 11

, giant stones along the northern face of tower 11

architecture. Perhaps it was an experiment carried out by an innovative architect, the purpose being to build the ultimate tower that no siege machine, mining team or earthquake could bring down. Huge building stones appear also in Safad, which had a remarkable Mamluk keep built in the center of the fortress (see below).

Latrines: small but important improvements

The additions planned y the Mamluks made garrison life more comfortable. Latrines were built of stone and set in a hidden corner within the towers so that some form of privacy was provided. The latrine was connected to a channel, flushed with water and drained into a separate cistern.

83

Although the construction was simple it meant the building needed a substantial amount of water for flushing the system clean, as well as for drinking and washing. It appears latrines were regarded by the Mamluks as a basic necessity rather than an item of luxury.

Water cisterns

Although the region of Mount Hermon has a fairly high amount of rainfall the long summer months are hot and dry. The supply of water in the fortress depends on accumulation of run-off water during the winter months. There are nineteen water

reservoirs at . The majority seem to have been built by the Ayyubids. The Mamluks added a few, possibly because the garrison was enlarged and the water supply had to be increased. It also may indicate a certain improvement of the standard of living within the fortress.

. The majority seem to have been built by the Ayyubids. The Mamluks added a few, possibly because the garrison was enlarged and the water supply had to be increased. It also may indicate a certain improvement of the standard of living within the fortress.

It seems more than likely that the towers and galleries were used for housing the garrison; they were spacious and had many of the basic requirements. Although much of the fortress is well preserved we know nothing of its inner buildings such as the whereabouts of the armoury, stables, storage, kitchens, dining quarters, smithy and mosque. The sources are silent and much of the central grounds of will have to be excavated before any of those questions can be answered.

will have to be excavated before any of those questions can be answered.

Safad

The medieal fortress of Safad is located in the upper Galilee, in the center of the modern town that carries the same name. The grounds of the fortress are covered to a large extent by a pine grove that serves as a local park; its outskirts have long since been paved and partly built over. Only very few sections of the structure can be seen today. Excavations have been conducted on the site since the early 1950s and in recent years by the Israeli Antiquities Authority. Although important evidence has been uncovered, the area excavated is still very small.

84

The sources, on the other hand, are detailed and a fairly clear outline of the site can be drawn if they are carefully followed.

The five main sources

Medieval Safad was a small village. It was only after the Crusaders decided to build a fortress there that the site began to attract the attention of Muslim chroniclers.

85

Five of the six main sources, including a French author, are written by contemporaries who lived in the second half of the thirteenth and in the early fourteenth century, when the fortress was being built by the Franks and rebuilt by the Mamluks. The anonymous French writer gives a comprehensive account in his work titled “De constructione castri Saphet,” where he describes the building of the thirteenth-century Crusader castle, emphasizing the first phase of the work (1240–3).

86

This source has been referred to and analyzed by most scholars who have discussed the construction of Frankish Safad at any length; therefore I shall refer to it only briefly. It is the only account that gives a clear idea of the fortress as the Mamluks saw it in 1266.

From 1266 onwards the additional buildings and repairs carried out by the Mamluks are presented by four Muslim authors. Ibn Shaddād and Ibn both give long and elaborate accounts of the work conducted by Baybars immediately after the siege. Each emphasizes different parts of the fortress. Of all the Muslim historians who wrote about Safad in this period, al-Dimashqī (d. 727/1327) who died there,

both give long and elaborate accounts of the work conducted by Baybars immediately after the siege. Each emphasizes different parts of the fortress. Of all the Muslim historians who wrote about Safad in this period, al-Dimashqī (d. 727/1327) who died there,

87

and (696/1297–764/1363), who was born there and later returned for a short period,

(696/1297–764/1363), who was born there and later returned for a short period,

88

are probably the only ones who saw the fortress with their own eyes. Their accounts are similar, short and rather colorful. adds an important fact to the chronology of the Mamluk building and states that the large central tower was completed during the reign of Qalāwūn.

adds an important fact to the chronology of the Mamluk building and states that the large central tower was completed during the reign of Qalāwūn.

89

Al-Dimashqī’s attention was caught by the fascinating mechanism

of the well with its chain of buckets that drew water from the cistern beneath the round central tower. His precise account leaves little doubt that al-Dimashqī had seen and studied the fortress carefully.

90

It was the stronghold’s impressive size rather than its military importance that attracted the interest of most of the Muslim contemporary chroniclers. None of them mentions its military significance.