Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (40 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

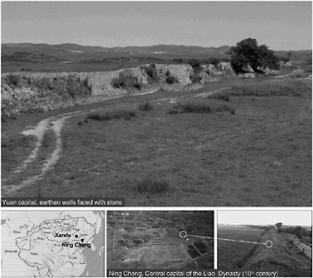

Figure 2.3

Earthern walls in northeast China and inner Mongolia (tenth to thirteenth centuries)

Map 2.1

China and Mongolia [bottom left]

Was gunpowder brought over to the Middle East by the Mongols?

One of the most controversial and intriguing issues debated among a wide range of scholars is the arrival and development of gunpowder. The differences of opinion concerning the use and efficacy of gunpowder during the thirteenth century call for a short survey. The majority opinion is that gunpowder was used by Chinese armies in the mid thirteenth century and even earlier. This group includes the following scholars: Goodrich, Chia-Shêng, Allsen, Khan, Martin, Chase, DeVries and Needham. Needham has conducted the most extensive archaeological and historical research on the subject of the development of gunpowder and firearms in China,

46

arguing that by the mid thirteenth century the Chinese could destroy city gates and walls using gunpowder.

47

He cites the four sieges in which gunpowder was used: Kayfeng (1232), Merv, Samarqand,

48

and probably also during the siege of Baghdad (1258).

49

Martin, who carried out a thorough study of the Mongol army, holds a

similar opinion.

50

Khan, who surveyed the sources that cover the Mongol invasion of the Delhi sultanate, found sufficient evidence that gunpowder was used by the Mongol forces.

51

Allsen also believes that gunpowder began to be utilized around the same time, but presents his opinion with some caution. Among the one thousand households Hülegü brought with him on his campaign to the west, he thinks there were men who knew how to produce gunpowder. Allsen says that at the battle near the Amu Darya (1220) the Mongol army fired rockets launched with the help of gunpowder.

52

Like Needham, Allsen claims that during the siege of Baghdad the Mongols used some form of gunpowder. Many scholars rely to a great extent on the studies published by Needham. Franke and May are currently among the few who clearly state that even at the end of the Yuan Dynasty (1368) gunpowder was not a weapon that could determine the outcome of a battle. According to May “its use remains speculations.”

53

Franke’s conclusions are based on a survey of the archaeological finds and the historical sources, all of which show that the number of casualties as a result of the use of gunpowder was very low. Ayalon demonstrated the problems of terminology in the Mamluk sources. His conclusion was that there is no definitive evidence that firearms were being used during the thirteenth and the first half of the fourteenth century, and that gunpowder was no more than an incendiary.

54

Returning to the question of whether the Northern Chinese contingents in Hülegü’s army employed gunpowder technology in siege warfare requires an examination of the three sources that give an account of his army on the eve of his journey west.

• Te earliest source was written by Malik Juwaynī, a Persian official who served the Mongols (d. 681/1283). The

Malik Juwaynī, a Persian official who served the Mongols (d. 681/1283). The

Ta’rīkh-i jahān-gushā

(‘History of the world-conqueror’) is an encyclopedic history of Chinggis Khan and his times that documents the events till 1257.

• Te second source was written by the Persian historian Rashīd al-Dīn Allāh Abū ‘l-Khayr (d. 718/1318). The

Allāh Abū ‘l-Khayr (d. 718/1318). The

Jāmi

‘

al-tawārīkh

(‘Complete Collection of Histories’) is the first universal history and was compiled ca. 1310 (an earlier version was completed in 1306–7).

55

It records the history of the Īlkhānid state established by Hülegü soon after the fall of Baghdad and the execution of the Abbasid Caliph (1258).

• Te latest source is the

Yuanshi

, a Chinese official history of the dynasty founded by the Mongols, compiled ca. 1370.

Neither Juwaynī nor Rashīd al-Dīn, both of whom describe Hülegü’s campaign, mention the use of gunpowder by the siege units of the Mongol army. It is perhaps possible that they were not familiar with this new weapon and described it by the terminology often used for the various incendiary weapons that were known among Middle Eastern armies. However, this does not seem to be the case. Both works contain only a short paragraph on the whole subject of the Northern Chinese siege units and neither notes anything unusual or new concerning the arsenal of Hülegü’s army. Thus it seems more than likely that Mongol methods and weapons did not appear strange or unknown in the field of siege warfare.

A close examination of the Persian and Chinese texts is important to fully understand the matter at hand. Juwaynī says that among the siege units there were soldiers specializing in hurling . The Persian term he uses is

. The Persian term he uses is andāzān

andāzān

.

56

Rashīd al-Dīn mentions these very same units and uses the same terminology to describe the men who hurl . In addition, he writes that among those siege units were teams he terms the

. In addition, he writes that among those siege units were teams he terms the

charkh andāz

. The Persian word

charkh

literally means “a round object,” while

andāz

means “to throw” or hurl.

57

Rashīd al-Dīn is in fact referring to the teams operating the siege machines that hurled round catapult stones.

The Chinese source is more complex than the two Persian ones.

58

The

Yuanshi

describes the recruitment of craftsmen/artisans for the siege warfare units in the armies of Chinggis Khan and Ögedei.

59

In 1252 Hülegü’s siege units were summoned from the same source of manpower. The term used for a particular craftsman in Chinese is a combination of two words. The first describes the raw material utilized by a specific craft. The second is

jiang

which can be best translated as smith. The list in the

Yuanshi

includes blacksmiths who work with iron, smiths who work with wood, i.e. carpenters, and smiths who work with gold, i.e. goldsmiths. The last raw material mentioned in the list is

huo –

fire. In contrast to the first three combinations which use the word

jiang

,

huo

appears on its own. It is therefore difficult to translate and reach a definite conclusion concerning its exact meaning in this context. The term

hou jiang

does not appear at all in the

Hanyu Dacidian

(the Chinese 12-volume dictionary) or in the

Ciyuan

(a dictionary orientated towards classical Chinese). The term

hou jiang

appears once more in the

Yuanshi

and there too comes directly after a mention of goldsmiths. Further, the combination

hou jiang

never seems to appear in any of the other earlier or later official Chinese histories such as the

Mingshi

,

Jinshi

, or

Songshi

. It is therefore difficult to conclude that the Mongols used gunpowder in siege warfare or to assume that they had men in their siege units who knew how to produce gunpowder. The fact that the Persian sources are silent and do not mention a dramatic debut of a new technology brought by the Mongols, as well as the fact that they simply stick to terms that were well-known in descriptions of siege warfare in Persian texts, further supports the view that gunpowder did not arrive in the Middle East with Hülegü’s Mongol army.

Chuang zi nu: the giant crossbow