My Time in Space (22 page)

Authors: Tim Robinson

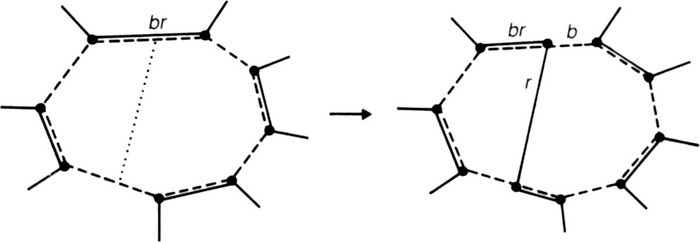

Fig. 25. How to colour a link spanning a circuit.

Beyond this point matters become increasingly complicated. A series of theorems is deduced, rich in content and succinct in expression, whcih seem to me much more vivid than the tedious demonstrations standard texts on the subject drag one through, only to abandon one in the Sahara Desert of the computer proof. But perhaps I have said enough to persuade the reader that Spencer-Brown provides the tools with which the four-colour theorem can be broached. In fact he claims that

… if the four-colour theorem were false … the whole of

Laws

of

Form

would be invalid. But since

Laws

of

Form

clearly is valid, the four-color theorem must be true. This is so evident, even without further

elaboration

, that it was considered an adequate proof of the color theorem by all the major mathematicians to whom I published it in the early 1960s, Bertrand Russell, JCP Miller and DJ Spencer-Brown.

As for the proof published by Haken and Appel in 1977,

according

to Spencer-Brown:

It may, or may not, be possible to prove the color theorem the way they claim. What is now certain is that they did not do so…. Of course they did not set out with the dishonest intention of claiming a proof they did not have. No one but a fool would do that. They must have felt certain that what remained to be done would be easy, and that they could do it between the announcement and the publication. And when they found it wasn’t and they couldn’t, there was no way to save face except to brazen it out…. You might have thought, somewhere in that mass of obscurely written jargon there might be a proof lurking. I am afraid you will be disappointed…. It is the most ridiculous case of ‘The King’s New Clothes’ that has ever disgraced the history of mathematics; the

imaginary

‘proof’ has been pumped out with propaganda and millions of

dollars

of misguided public money, and none of those involved now dares admit that nothing of any value has resulted.

And the obverse of this canonization of the Haken-Appel proof has been, he tells me, the demonization of Spencer-Brown. His own proofs have only appeared in rather obscure quarters, and few mathematicians have troubled to learn enough of his

techniques

to appreciate them; no ‘experts’ followed the seminar

Martin

Gardner referred to. I myself have spent many days with his papers, and can report that not only are they without taint of charlatanry but they contain mathematics of Mozartian grace and clarity. Once the extremely compact symbolism has been unpacked, most of the concepts and methods are of luminous simplicity.

Spencer-Brown has great faith in the mathematical ability of youngsters (he writes somewhere to this effect: ‘If a child asked me for a toy I would say, “Here is the number system. It costs nothing, it will give you entertainment for a lifetime – and you can’t break it!”’), and I can envisage future generations of school children enjoying the way his operations send colour-changes flickering all around networks and suddenly reveal the way to colour in that last link.

But do these innovative methods lead to unshakeable proofs? The four-colour theorem is notoriously a logical Bermuda

Triangle

into which many a bold flight of intellect has vanished. A

difficulty

in coming to a judgement here, apart from the complexity and subtlety of his arguments, is Spencer-Brown’s persuasion that certain quite complex mathematical facts are obvious and hardly need demonstration. For instance one of his proofs follows, he claims, from a certain ‘self-evident proposition’ – and he then interjects, ‘If you do not yet see this as self-evident, do not persist with this proof.’ Of

the four-colour theorem itself he writes, ‘Everybody knew it was true, so it must always have been

subliminally

obvious. And this is what made it so difficult to prove…. Subliminal awareness goes to the heart of the problem, but

consciousness

invariably takes a long way round before trying

anything

simple.’ The mathematician, through repeated mental handling of abstract objects, acquires a feel for their properties which is as difficult to convey in explicit terms as our sense of the leverage and balance of knives and forks. Whether such

sure-handedness

can be delusory, whether in the particular case of Spencer-Brown’s grasp on the four-colour theorem there is no slippage and fumbling, is beyond me to say. But, if pressed – and the momentum of this essay does press me – I would risk a claim

that once some clarifications have been carried out, gaps made good, and the smoke and dust of a paradigm-shift have settled, his proof will appear in all its originality and irrefutability. And of this I am sure: an injustice has been done him, and a body of

mathematics

that should have been subjected to the normal trials by peer-criticism has been disregarded. That is a crime against both truth and beauty – for Keats’s equation of those two excellencies holds better in mathematics than in any other field.

*

For later editions the author hyphenated his name, as Spencer-Brown.

Searching the London Library for old books that might throw light on the history of Connemara, I came across

The Saxon in

Ireland

, or, the rambles of an Englishman in search of a settlement in the west of Ireland,

published by John Murray in 1851; anonymous, but with the name John Henry Ashworth written into the title page by librarian’s pencil. Its professed intention was ‘to direct the attention of persons looking out either for investments or for new settlements, to the vast capabilities of the Sister Island’, and it goes into great detail on the manuring of land, the Incumbered Estates Act, and other practicalities; I suspect it was also intended to boost the author’s own courage and that of his family in facing

emigration

to the Ireland of that still famine-stricken date, for it is remarkably positive in outlook, and one has to read the small print of quoted matter in the appendices to find a mention of potato blight. I did glean a few grains of information on Connemara, but it was an incident from his travels in Mayo that has lodged in my mind. In Ballycroy, a remote glen of Erris, the author calls upon another Englishman, Mr S, who tells him about the strange

meeting

which led to his own settling there. This episode, quite out of keeping with the rest of the book, is entitled ‘The Echo Hunter’. I have trimmed it a little.

I was at Ballina, sitting at the open window of the inn, when the

melodious

sounds of a bugle, playing a beautiful Irish air, attracted my

attention

. No long time had elapsed when a little dapper-looking gentleman, of middle age, entered the room, with a bugle in his hand. ‘I have to thank you, sir, I presume,’ said I, rising and bowing, ‘for the great treat I have just enjoyed?’ ‘You have to thank me for very little, sir,’ replied he, carelessly; ‘This instrument is all very well, but I seldom use it except to rouse Dame Nature, whom you will find sleeping among the crags and cliffs. The moment I sound my bugle, an answer comes from the mountains, no less singular than beautiful, leaping from rock to rock, now loud, now murmuring, but always sweet.’

‘Excuse my dullness,’ said I, smiling; ‘I understand you now; you mean the echo.’ ‘Why yes,’ he replied, ‘echoes according to the common language of the world; I call them the voice of awakened Nature. There is nothing in the theory of sound that can satisfactorily account to me for the wonderful voices my bugle has awakened in certain spots which I have discovered; but I do not make them generally known, for – laugh if you will – I have a notion, which I like to encourage, that Nature loves solitude, and would ill brook the being disturbed by every common idler. I have travelled through and through Ireland, meeting with such echoes in many a sequestered nook, unnoticed by any one before me, but

Ballycroy

, yes, sir, not twelve miles from hence – Ballycroy exceeds them all. But,’ said he, lowering his voice, ‘it were vain for you or any other

mortal

to attempt to find out these peculiar spots. I alone discovered them, and with me the knowledge of their existence will die.’

Ere we parted for the night, he invited me to accompany him on the following morning on an excursion into the Ballycroy mountains. He placed me on a certain spot; and exacting a promise that I would not

follow

him, he retired, and in about a quarter of an hour gave me such a treat in his peculiar art as I can never forget. The rocks and mountains seemed alive with harmony; the softest and wildest notes floated in the air, now close, now distant; now dying away in some distant recess of the valley, now awakening louder and louder among the cliffs and precipices;

at one moment faint as the whisper of the breeze, at another loud, clear, and bold as the trumpet of the Archangel. I never before or since

experienced

the sensations which at that time overpowered me, and I no longer either smiled or wondered at the zeal of my new acquaintance in his peculiar and eccentric pursuit.

Ballycroy was at that time for sale. Mr S was moved to buy it up, and subsequently turned the wilderness into a valuable property. Only once after that did he meet the Echo Hunter:

When I last caught sight of him, he was leaning pensively against the rock, round whose base we turn on entering the glen below us. He

congratulated

me upon my improvements, but declared significantly that ‘Art would drive out Nature.’ ‘This’, he said, ‘is my last visit to this

valley

; it was once a favourite spot of mine, but the presence of man has tainted it. In Corranabinna I am safe from intrusion. There man will never pitch his tent; it is too near the sky.’ After we had parted about ten minutes, a few discordant notes of his bugle awakened a thousand more discordant echoes, and I never saw him more!

‘The Saxon’ is both affected and encouraged by Mr S’s story, and when it is finished the two of them sit in silence for some time. Looking out on the comfortable scene of ‘pastoral wealth’ Mr S has created, he feels a strong conviction of his own success in a similar experiment. That the discord, quite obviously, is between the profits of cultivation and nature’s loss, is not spelled out, and the book goes on its way as if the Echo Hunter had never sounded such a note.

Since those days in which a new dispensation of capitalism was replacing the old landlords bankrupted by the Famine,

development

of Ireland’s ‘waste lands’ has advanced, very slowly and with many setbacks. The land had to be drained of tears; one cannot forget that, in weighing up profit and loss. Also, areas such as

those I have been concerned with in the western counties have not been untouched wildernesses for several thousand years; humankind has settled them intensively in some periods, building, cultivating, naming. In fact this is the sort of land I love, that has been finely and repeatedly discriminated into multitudinous place by use of stone and word. I have peeped into the Grand Canyon and rapped on the windows of a Norwegian glacier, but such life-threatening giant terrains are not central to the map of my empathies. In the west of Ireland are territories where a

proportion

is still preserved; nature has room for its ways and so does humanity. This sphere of interaction and qualified autonomies has its echoes and the echo hunters necessary to their awakening, its sheerest cliffs have names and histories, its placelore knows a

gradation

of familiarity from town centre to lonely upland. Without defining it more tightly, I’ll call it the Echosphere; the word has been lying around in my mind for years awaiting an application.

Descending to the local and personal scale of my time in the west of Ireland, which has coincided with a surge of economic growth, I am as aware of cultural loss, loss of history, loss of echo, as I am of ecological damage. I have come to resent the

truth-telling

of environmentalism; a sense of the Earth’s vulnerability and of the obligation to defend it hangs a veil of anxiety between me and the landscape. At every turn of my walks I expect to find some detail of the scene that I have lovingly and scrupulously noted in one of my maps or books, effaced by careless ‘

improvement

’: a JCB levelling a site for a house has needlessly scooped away an old limekiln; a road-widening scheme has heaped rubble onto a stone commemorating the death of a friar at the hands of priest-hunters. Is it mere ignorance and indifference, or does some wordless animosity drive this destruction of the countryside and the little landmarks that make it meaningful?

In 1998 I was asked to write a background note on

Connemara

for the programme of the Druid Theatre’s first production of Martin McDonagh’s plays

The

Beauty

Queen

of Leenane,

A

Skull

in

Connemara,

and

The

Lonesome

West.

I took it as an opportunity to release my pent-up rage in a diatribe directed against all that I had previously written on Connemara:

A CONNEMARA IN THE SKULL

We don’t see much of the outside world in McDonagh’s trilogy – a

cemetery

by night and a favourite lakeside suicide spot are the only excursions allowed from his comfortless kitchens. In the first play we hear: ‘All you have to do is look out your window to see Ireland. And it’s soon bored you’d be. “There goes a calf.’” Is the Connemara out there a fit setting for these desperate comedies? If so, it is not the Connemara of

cloud-shadow

connoisseurs.

This crossbones landscape is the outcome of six thousand years of human demand. Stone Age agriculturists fired and felled the oakwoods; already by the Bronze Age peat bogs were spreading across exhausted soils. Centuries of bog growth almost closed off the interior and confined history to the shoreline. The potato came, and an exploding population crammed into a narrow coastal zone was forced to strip the peat away, as fuel for itself and for the growing city of Galway, leaving naked granite. When the potato rotted, in 1845–49, a frugal and ingenious peasant

ecology

, already screwed to the limit by an extortionate social system, collapsed into beggary and despair. Connemara still lives in the aftermath of

millennial

famine, of age-old physical and psychic deprivation. Who were the expropriators? Is it true, as one of McDonagh’s characters holds, that the ‘crux of the matter’ is ‘the English stealing our language, and our land, and our God-knows-what’? For the record – and it is complex and ambiguous – the masters of Connemara from the Middle Ages to the

Cromwellian victory in 1650 were the Gaelic O’Flahertys, and folklore associates every one of their castles with murderous tyranny. In the Leenane area the Joyces, originally Norman-Welsh but thoroughly Irishized, held power under the O’Flahertys and later adapted profitably to the role of middlemen under the new landlord instated by the

post-Cromwellian

settlements, Trinity College Dublin. The will to

exploitation

is general; the opportunity for it passes from hand to hand.

When, towards the end of the last century, agrarian terrorism forced the British government to undertake the development of the West, one result was that the landlords were bought out, the companionable old clusters of hovels broken up, and the former tenants installed in isolation, each

family

in its own cottage on its own stripe of land. Was this one of the

traumas

, along with the death of the Irish language and the sealing up of the oral tradition, that has made rural life an insult to its setting in nature and the past? A walk in today’s pastoral landscape is a succession of affronts to one’s sense of belonging in the world. Stroll up the boreen: you may remember it as charming from ten years ago, but you will find that the flowery hedgerows have been ripped out in favour of barbed wire, and that the old cottage is roofless, replaced by a gaunt bungalow facing a huge shed of concrete blocks and galvanized sheeting. In the slovenly yard is a silent dog condemned to life on the end of a chain. Cross a hillside black from the burning-off of furze, all its larks’ nests, lizards and butterflies

incinerated

; skirt round the dead sheep caught in briars by its neglected tangles of wool; stride out with relief across the open mountainside. But the

heathery

slope has been turned into an irreparable morass by overgrazing, the ruthless grant-driven multiplication of undernourished ewes too weak to feed their lambs. If you meet the shepherd of this desert of suffering, he will tell you he must be compensated before he considers reducing his flocks so as not to leave his own children a barren inheritance. There is more, much more. The news from Connemara’s waters is equally squalid:

brown-trout lakes contaminated with sewage, slurry and fertilizers, the salmon’s spawning beds overwhelmed by peat washed down from the

eroding

mountain, sea trout with their fins eaten away by lice from the

concentration

fishfarms in the bays …

No need, I hope, for me to say that this is not the only Connemara – I have written at length about beautiful and hopeful Connemaras – but there is no doubt that this Connemara exists, this calamitous backdrop to the society McDonagh shows us, fled by its young, with its brutalized law and its old church gone in the teeth. The machine of his theatre forces us to laugh even as we pity and shudder at all this, and the bare beauty of Connemara is one of his grim implicit jokes. Perhaps it is even close to the ‘crux of the matter’.

However, in case after case, there is no time for correct

philosophical

naming of the crux of the matter; something is under immediate threat, and action is called for. I will note some phases of two campaigns I have been conscripted into by obligations incurred through writing.

*

Roundstone Bog is a terrain I became aware of through the

writings

of the naturalist Robert Lloyd Praeger even before I came to live in Roundstone itself; indeed it was one of the factors behind our settling here in 1984. A mere half-hour’s walk from the house, it lies far outside the habitual; it offers extremes, physically and mentally. I can best introduce this aspect of it through a piece I wrote for the launch of

Nature

in

Ireland,

John Wilson Foster’s study of Irish natural-history writing, in 1998: