Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (19 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

For a long time I wondered where the

bouquinistes

got their books. From regulars like me, certainly, but small-time, occasional swap-traders are notoriously unreliable. It turns out that several days a week most

bouquinistes

rise before dawn’s fingers start tickling the Seine, and drive to the scruffy suburbs or distant provinces to scour flea markets, attend auctions, or hit village yard sales—the best sources for books. Sometimes middlemen arrive with a truckload jumble rescued from an attic somewhere. Occasionally, burglars try to peddle stolen tomes, but street-smart sellers usually spot hucksters before they get a chance to finish their spiel. Or so it’s said.

Competition comes not only from the Web and high-tech, or other secondhand bookstores. Every weekend year-round the Georges-Brassens book market is held under a nineteenth-century glass-and-iron structure at the Parc Georges-Brassens in the far-flung 15th arrondissement. It has become another favorite of serious collectors, though it lacks the charm—and convenience—of the quays.

Of Paris’s approximately two hundred forty

bouquinistes

, perhaps two dozen are specialized—in crime novels, music books, military history, fine art, old magazines, incunabula, and so forth. When I’m looking for thrillers or jazz-related books, I go to bearded, affable Jacques Bisceglia, whose boxes face 31 Quai de la Tournelle. He has the biggest jazz-book collection in town, about eight hundred volumes, plus thousands of crime novels and detective stories—his second passion.

Across the Seine from Jacques, facing 48 Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville, a vigorous fellow named Michel Vigouroux, originally from Brittany, sells every book, magazine, or poster imaginable relating to his windswept native region. Down the same quay, Katia Lachnowicz, across from number seventy-two, deals in movie and theater books. Agnès Talec, facing 21 Quai des Grands-Augustins, displays almost every leaf of high-minded literature published by La Pléiade, while Jean-Claude Picon (across from 2 Quai de Gesvres) boasts a nearly complete collection of

Paris Match

—ah, for those weighty words and punchy photos! Some of the finest engravings and rare vintage books in town (and among the most expensive—up to one thousand dollars) are the specialty of Left-Bank institution Michelle Huchet-Nordmann (facing 35 Quai de Conti).

For most other

bouquinistes

, however, variety is the key to survival, so they sell a mixed bag. That means a dedicated

bouquineur

can spend entire days browsing the hundred Right-Bank

emplacements

between the Pont-Marie and Rue de l’Amiral-de-Coligny before crossing the Seine to the remaining hundred-fifty between the Pont Sully and Pont Royal. It’s a workout but the views aren’t bad and the characters you meet are often salty specimens of

homo parisianus

.

Fiercely independent, sometimes extroverted, sometimes surly, the

bouquinistes

are a caste apart. Solidarity is essential to survival. It takes about forty-five minutes to open or close a stall, for instance, so neighbors usually help each other. They share bottles of wine and stories, passing information along the quayside jungle

téléphone

. They know each other. They know who’s selling what and for how much, and refer clients back and forth. Among themselves, they use only first names—“Go see Robert for that,” they might tell you, giving an “address” as people once did before the days of street signs, “in front of Le Montebello …”

Robert, it turned out, was Paris’s oldest working

bouquiniste

when I met him, a big man still at eighty-something, with luxuriant moustaches and a beard. He sells collectors’ books and cheap paperbacks too, from a spot facing Le Montebello, a restaurant on the quay of the same name. Another celebrated sidewalk character is Jean-Jacques, whose

emplacement

faces 31 Quai de Conti. His nickname is

le Jacques Prévert des bouquinistes

, apparently because he’s an expansive rhetorician. His passions are film, theater, and dance, and he doesn’t have much time for uninitiated browsers.

One hundred yards east of Jean-Jacques, facing 55 Quai des Grands-Augustins, an eccentric newcomer to the business is a retired communications consultant named Guy. He sells a wide variety of books, but his true interest lies in exhibiting his own original oil or pastel paintings, which range from the figurative to the abstract. Purists scoff at Guy, seeing in his unconventional “gallery” the narrow edge of a Montmartre-style wedge. But it’s hard to label his paintings as any more tasteless than the hundreds of pseudo-Sigmund Freud posters (“What’s on a Man’s Mind?—A Naked Woman!”) on offer at dozens of other stands, and it’s unlikely Montmartre’s elephant train will ever catch on here.

I once conducted an informal survey, asking

bouquinistes

if they enjoyed their life. Most waxed lyrical about the freedom of being independent, the wonders of the book world, the magic of the quays, and the stimulation of daily encounters with people from around the world. But if pressed they often sighed or confessed. Weather is the

bouquinistes

’s main worry. Rain, especially, makes business difficult. Snow, high wind, cold, or burning sun can keep people off the quays for days at a time. And the elements take their toll on the booksellers themselves. “We’re the peasants of Paris,” said one wizened oldtimer I queried near Notre-Dame. “We listen to the weather reports like fishermen or farmers, then we come out anyway and get soaked, frozen, or sunburned.”

You can account for the surliness of some

bouquinistes

by the combination of weathering and wear. They’re stone-washed by the incessant tides of curious tourists who pick up books, unwrap them, put them back in the wrong place, and seem more interested in rummaging than buying. Then there are the city authorities and tax inspectors—always eager to check on strictly cash-in-hand businesses.

Most annoying and dangerous of all, however, is the car, truck, and bus traffic that thunders by, ever faster and thicker and more poisonous as the years go by. In the early 1990s, UNESCO declared the quays of the Seine a World Heritage Site, yet at the same time the city of Paris turned them into

axe rouge

expressways. Every stoplight is the start of a drag race. By afternoon, if there’s no breeze, the air can be black with smog. The

bouquinistes

shake their heads at this and mutter words such as “nightmarish,” “idiotic,” and “incomprehensible.” A modicum of relief has come of late in the form of the bike and bus lanes on the Left Bank and, in some places, wider sidewalks, but not all

bouquinistes

have benefited.

Despite the difficulties, the average age of the men and women on the quays has dropped from sixty (in the 1960s) to forty—proof of the profession’s stubborn vitality or, perhaps, an indication of a desperate economic situation that drives the young toward marginal businesses. One thing is certain, there’s never a shortage of applicants vying for a license or a spot. The waiting list usually stretches about eighty names long. It takes up to four years to get your first

emplacement

—always in a lousy location—and it might take you decades of hopscotch to wind up near Notre-Dame or the Pont-Neuf.

“You start in Purgatory,” lifelong

bouquiniste

Laurence, near the cathedral, explained to me. “Purgatory is what we call the bad spots on the extreme ends of the quays—like the one my grandmother got in 1920 and I got twenty years ago. From Purgatory you work your way to a better life.” She smiled, pointing to the buttresses of Notre-Dame soaring above the Seine’s leafy banks. When the traffic had subsided, for a blissful moment, it did indeed seem like we were in Paradise.

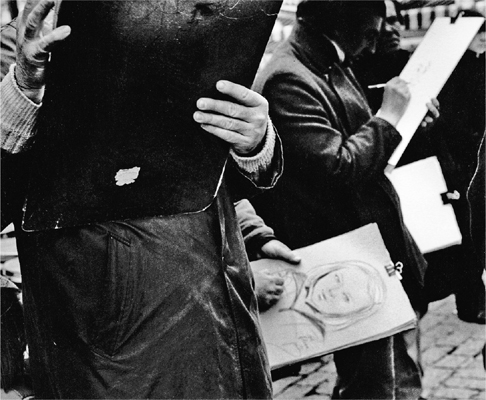

Midnight, Montmartre, and Modigliani

It is a strange gray study in nature, this midnight Montmartre … Artists with hope before them, poets with the appreciation of some girl only, and side by side with these the hurried anxious faces of unkempt women and tired-eyed men …

—H. P. H

UGH

, 1899

harles

harles

The-Flowers-of-Evil

Baudelaire was nineteenth-century Paris’s archetypal

artiste maudit—

the tortured, sensitive, cursed poet of a dead city that had crossed in a single generation from the Middle Ages into the modern age. He lived intensely and died young, his work imbued with a deep melancholy that resonates to this day. In many ways, the Franco-Italian painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani picked up in the early 1900s where Baudelaire had left off. It was a dubious honor, perhaps, but Modigliani’s soulful artwork, like Baudelaire’s poetry, is more coveted than ever, and the story of his tumultuous, debauched, tragically short life in Paris is as moving today as it was a century ago.

A puritanical biographer of our current age might describe Modigliani as macho, womanizing, obsessive, and demonic, a substance-abusing madman too handsome and talented for his own good, at once self-destructive and murderous, a kind of proto–Jim Morrison (of the Doors), a rebel without a cause, the last of the great bohemian Romantics of the Belle Époque.

Like Jim Morrison, Modigliani is buried at Père-Lachaise cemetery, the graveyard of France’s great and good. I have often thought of the tragic pair as I stroll among the tombs. So when a few years ago Alison and I set about mapping the places where Modigliani had lived, worked, and died, Père-Lachaise seemed the logical place to start. Division 96, Avenue Transversale number three is Modigliani’s address, in theory for perpetuity. It corresponds to a simple limestone tomb in an uninteresting section of the cemetery. Nearly always covered with flowers, the gravestone bears the inscription: “Amedeo Modigliani, born in Leghorn July 12, 1884, died in Paris January 24, 1920. Death snatched him from the brink of glory.” Modigliani died a pauper. But, as Alison, an art historian by training, reminded me, he had a hero’s funeral, attended by Picasso, Soutine, Léger, Ortiz de Zárate, Lipchitz, Derain, Severini, Foujita, Utrillo, Valadon, Vlaminck, and the poets Max Jacob and André Salmon, as well as dozens of now-forgotten friends and admirers. He’d found glory, certainly in terms of peer recognition, but it came too late.

Farther down Modigliani’s tombstone is a second, cryptic epitaph. It was added some years after the first and reads: “Jeanne Hébuterne, born in Paris April 6, 1898, died in Paris January 25, 1920. Devoted companion of Amedeo Modigliani till the moment of extreme sacrifice.”

Extreme sacrifice? I wondered who Jeanne Hébuterne had been and why she’d died just a day after the artist. Alison had only a vague recollection, so before setting out to find the places Modigliani knew, we dipped into the art history books and were fascinated and horrified in equal measure by what we found.

Amedeo Modigliani’s mother was French, from Marseille, his father Italian. Both descended from solid, middle-class Jewish families. Amedeo grew up on the Tuscan coast and moved to Paris when twenty-one to study art. A freethinker, he abjured the family faith and declared to his fellow students that he wanted “a short but full life.” Dashing, charming, witty, and perfectly bilingual, Modigliani got his “full life” off to a galloping start—he drank heavily, smoked hashish, partied and painted round the clock, changing addresses and lovers about as often as his clothes. It’s unclear what stage his consumption, a deadly lung disease, had reached before he arrived in Paris. It’s irrefutable, though, that Modigliani was obsessed by fears of the congenital insanity that had plagued his family for generations. He dwelled morbidly on his own impending death, and as his physical and mental health declined he began flitting around the cemeteries of Montmartre and Montparnasse reciting lines from Dante’s

Inferno

and

Les Chants de Maldoror

by Isidore Ducasse, known as le Comte de Lautréamont, the notorious adept of De Sade. Tellingly, the nickname his fellow artists gave him was Modi—short for Modigliani, of course, but pronounced exactly like

maudit

, meaning damned, accursed, the spiritual heir of Baudelaire.