Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (5 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Not far from a bronze statue of a stag and deer, and the busts of a score of forgotten men, famous in their day, stands a marble sculpture of Watteau posed beside a buxom demimonde. He seems pleased, at home, as do the drunken Silenus, falling off his mule, and the ecstatic Pan across the esplanade, whose lithe figure when glimpsed from the palace appears artfully framed by the Panthéon.

I took another turn around the grounds, this time to admire the monuments to Baudelaire, Verlaine, Gérard de Nerval, and Delacroix. These weren’t military men or industrialists. Demigods, poets and artists, like guardian spirits, have always inhabited this park. At their feet, children spin on an old merry-go-round, pedal antique tricycles made to look like horses and royal carriages, or roar at the antics of Guignol and Gnafron at the park’s eternal puppet theater. Ponies troop up and down, followed by zealous road-apple sweepers armed with worn brooms. Businessmen and bus drivers unknot their ties and troubles and play bowls in the shade of spreading sycamores.

As I drank in this cheerful spectacle, the bells of nearby Saint-Sulpice tolled four o’clock. Soon the gardens were swarming with perambulators,

poussettes, cochecillos de niño, carrozzine

, and whatever else the au pairs and young mothers choose to call a baby carriage in the Babel of languages they speak. Could it be the day-care centers had just closed? At length scores of starched-looking matrons from the luxurious apartments bordering the park were chatting away with immigrant maids and young bourgeois babysitters.

The words of Louis-Sébastien Mercier, written more than two hundred years ago, sprang to mind: “This peaceful garden is free from the extravagance of the city, and immodest and libertine behavior is never seen nor heard … the garden is full yet silence reigns.” In truth, there is more joyous laughter in the Luxembourg nowadays than reverential silence, and I’ll bet there always has been.

Before I knew it, the sun was dipping into the trees and the whistles of the

gardiens

had begun to blow. Children froze in their games. Lovers released their passionate embraces. Chess players stopped their clocks. And slowly, reluctantly, we took our leave as dusk spread above. I watched from outside the gates as gardeners, rarely seen by day, set to work with shovels and rakes, readying the Luxembourg for dawn.

A Lively City of the Dead: Père-Lachaise Cemetery

I rarely go out, but when I do wander, I go to cheer myself up in Père-Lachaise

.

—H

ONORÉ DE

B

ALZAC

, in an 1819 letter

fascination with death, what the French call

fascination with death, what the French call

nécrophilie

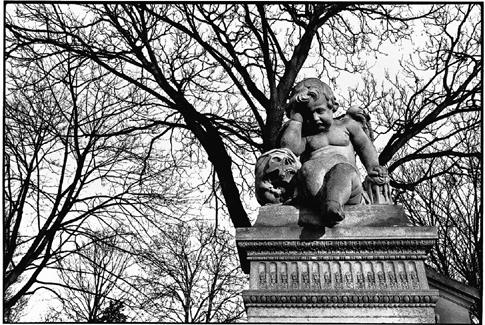

, takes many forms, one of them so common it afflicts some two million individuals who each year enter the hallowed gates of Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris’s 20th arrondissement. Hilly, wooded, with winding paths knotted around crumbling tombs, this is without doubt the most celebrated monumental city of the dead in Europe. Surprisingly it stands within the limits of the sprawling French capital. It also happens to be about 150 yards as the raven flies from the office I rented for twenty years, which is why I became a Père-Lachaise habitué. I love many things about the place: the greenery, the lack of cars, the expansive views from looping gravel lanes and, of course, the sepulchral monuments. Père-Lachaise quietly merges ancient and modern death cults, thereby assuring itself perennial status on the top-ten list of Paris tourist sights. Peak attendance nowadays is on the newly fashionable Halloween, an Anglo-Saxon holiday, and on November 1 and 2, the traditional All Saints’ and All Souls’ days. But the procession to Père-Lachaise of curious funerary pilgrims knows no season and braves all weather.

Amid the cemetery’s hundred lush acres stand faux Egyptian pyramids, mock Greek or Roman temples, and neo-Gothic chapels erected during the heyday of Romanticism two hundred years ago, when the cemetery opened for business. These are my favorite monuments, and their setting is wonderfully evocative. Moss-grown, lichen-frosted, and shaded by venerable, voracious vegetation, the graveyard’s first tombs were made in imitation of the antique, specifically of Rome’s tomb-lined Via Appia Antica. They too are now antiques—proof that time can render true what begins as falsehood.

Scattered among these proto-memorials are Second Empire neoclassical piles worthy of Paris’s notorious 1853-to-1870 prefect, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Fewer in number but more remarkable are the eerily delicate Art Nouveau fantasies from the turn of the nineteenth century. The modernist Le Corbusier–style slabs salted around are devoid, like that worthy Swiss genius, of any perceptible humor or humanity. Each tomb faithfully mirrors the times in which it was conceived. There are even a handful of postmodern pastiches—a cat’s cradle of Plexiglas, steel, and stone, for example—expressing the confused brutalism of recent decades.

The cemetery’s upper third marches across a plateau crowned, outside the cemetery’s walls, by Place Gambetta. In keeping with the precepts of the 1850s when this section was developed, the layout is a deadening, dull grid. Had it been easy, or even possible, Baron Haussmann’s minions would have done in the 1850s to Père-Lachaise what they did to Paris as a whole: tear up the meandering alleys and asymmetrical tombs, replacing them with an efficient checkerboard of plots for the disposal of the dead. But the modernizers failed, much to the relief of nostalgic lovers of Vieux Paris such as Victor Hugo, or Joris-Karl Huysmans. In his 1880

Croquis parisiens

, Huysmans lashed out against the “tediousness” of Haussmann–style symmetry, seeing in the higgledy-piggledy Père-Lachaise and its rural surroundings “a haven longed for by aching souls.”

Ironically, the thousand-plus seditious Communards massacred by Napoléon III’s troops amid Père-Lachaise’s tombs in 1871 are buried in the cemetery’s symmetrical Second Empire section. Haussmann, enemy of Communards and old Paris alike, wound up in Division 4, an older, less symmetrical area. He lies not far from such utterly un-Haussmannlike free spirits as Gioacchino Rossini and Alfred de Musset. Subversive Colette, lover of women and weaver of intrigue, is practically his neighbor, fifty yards away. There is no such thing as justice, poetic or otherwise, in death, the great equalizer.

What has preserved unpredictable Père-Lachaise from the compulsive straighteners such as Haussmann is a legal concept that, like religious faith, defies logic and in so doing attempts to deny the temporal nature of human life and institutions. That concept is the

concession à perpétuité

, literally a concession granted forever by the city of Paris to families who own plots at Père-Lachaise. This was a novelty in the late 1700s, when the plan to create cemeteries outside Paris was hatched. Until then nearly everyone was thrown into common graves: only important churchmen, nobles, and the very rich rated individual burials, usually inside a church, under the paving stones.

But new ideas on hygiene arising from the Enlightenment’s scientific advances, plus a renewed familiarity with the burial practices of the ancient Romans, led Paris’s administrators to ban inner-city cemeteries and under-floor burials in favor of sites beyond the city walls. The immediate stimulus for these reforms, however, came from the collapse of the cemetery of the Innocents (in the square of the same name near today’s Les Halles shopping center). When the bones and rotting corpses of millions of Parisians—about seven hundred years’ worth—burst through the graveyard’s walls into the surrounding neighborhood, administrators scrambled. They built the catacombs in abandoned quarries. Later, in 1804, they inaugurated the Cimetière de l’Est. “Eastern Cemetery” is the official name of Père-Lachaise to this day.

It may be hard to credit but in 1804 the site stood beyond Paris’s walls in rolling countryside. Known by various names, including Mont-Louis, the area had been covered since at least the Middle Ages by woods, vineyards, orchards, and market gardens. In the mid-1600s Jesuit father François d’Aix de la Chaise, better known as Père Lachaise, became Louis XIV’s confessor. An ambitious, worldly fellow, Lachaise eventually prevailed on the monarch to help him buy Mont-Louis and turn it into the country resort of Paris’s Jesuit brothers. Included in the deal was a nice little château for Lachaise’s personal use, perched at the hill’s highest point. The Jesuits were evicted in the 1760s and Mont-Louis passed through the hands of several private owners. Paris’s municipal authorities eventually bought it and created a graveyard to serve the city’s eastern arrondissements. Later still, the same authorities demolished Père Lachaise’s château. Since about 1820 a chapel has stood on the site.

What’s in a name? François d’Aix de la Chaise isn’t buried in the cemetery that bears his name (he reposes beneath the church of Saint-Paul, in the Marais). Apparently, when it first opened, the clinical-sounding Cimetière de l’Est didn’t seem like the ideal place to bury loved ones. For this reason the site’s earliest developers hit upon the scheme of calling it Père-Lachaise, to give it a hallowed, Jesuitical ring. Then as now religiosity was an effective marketing tool. The cemetery was not consecrated ground under the Jesuits and is not consecrated today. By law French municipal graveyards must welcome all sects, creeds, and religions, as well as agnostics and atheists.

These same developers used another clever marketing ploy to promote the cemetery. It involved relocating the tombs of a few famous dead, so that potential clients would be able to say, “Well, if Père-Lachaise is good enough for abbots and royalty it’s good enough for me.” The first celebrity corpses whisked to the cemetery were in fact those of the luckless abbot Abélard and his pupil Héloïse, the twelfth-century lovers whose tragic tale of emasculation (his) and enforced separation (mutual) was the rage among early 1800s Romantics. Abélard and Héloïse’s towering neo-Gothic tomb, still one of the most spectacular in Père-Lachaise, is the highlight of Division 7, the cemetery’s oldest section. For similar promotional reasons, Louise de Lorraine, widow of King Henri III, was shifted to Père-Lachaise from the convent of the Capucines, perhaps in a bid to entice Royalist customers. (Her tomb was later dismantled.) To make intellectuals and artists feel welcome, Molière and La Fontaine were disinterred from the Saint-Joseph and Innocents cemeteries, respectively, and placed in new tombs in Division 26, high on a hill. Never mind that the bones of both playwright and author had been mixed with those of other skeletons in a common grave; their tombs are in fact cenotaphs, since no one can be sure whose remains they hold.

Soon after these transfers, another celebrated playwright was dug up and moved to Père-Lachaise: Caron de Beaumarchais, author of

Le Mariage de Figaro

. His original grave in the garden of his townhouse on what is now Boulevard Beaumarchais stood in the way of progress, so the move was both convenient and necessary.

Though business was slow at first the twin ploys of the Jesuit’s name and the famous transplanted skeletons eventually worked. By the 1810s Père-Lachaise had become

the

resting place for families of high social standing or aspiration, those, in other words, with the money to buy a perpetual concession and build a monumental tomb. People spoke of the cemetery’s most desirable neighborhoods, paralleling them to Paris’s

beaux quartiers

. That explains why the roster of nineteenth- and twentieth-century marquee names with a slice of Père-Lachaise is a

Who’s Who

of France.

Among my favorite residents are botanist-agronomist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier of potato fame (his tomb is surrounded by potato plants), essayist Louis-Sébastien Mercier (author of

Tableau de Paris

and

Le Nouveau Paris

), military heroes Maréchal Ney and Kellermann (both rate a Paris street in their honor), not to mention Chopin, Balzac, David, Gustave Doré, Oscar Wilde, Guillaume Apollinaire, Amedeo Modigliani, Marcel Proust, Edith Piaf, Gertrude Stein, and Yves Montand. Just about every distinguished poet, writer, musician, composer, statesman, military hero, doctor, actor, playwright, scientist, blueblood, industrialist, and plutocrat of the past two hundred years lucky enough to have died in or near Paris is buried here. Montparnasse’s celebrated cemetery pales, ghostlike, in comparison.