Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (6 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

But it’s not merely the one million illustrious occupants of the seventy thousand tombs strewn picturesquely along ten miles of paths veining the cemetery’s panoramic parklands that draw visitors to this preternaturally Parisian necropolis. There is an additional, intangible attraction I notice each time I wander here: the cult of the dead, the fascination, sometimes morbid, that the living feel toward the related phenomena of death, time passing, and collective memory. This fascination takes many forms, and Père-Lachaise accommodates them all, embracing the rites of conventional Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, and adepts of black magic. Even believers in the transmigration of the soul are well served. For the delectation of Spiritists there is the flower-strewn sepulchral monument, perpetually besieged, dedicated to Allan Kardec, father of this curious creed. His tomb is in Division 44 near the crematorium and every time I pass it, Kardec’s followers are there by the dozen. They lay hands on the tomb and, they claim, communicate with their master.

Nature and the elements play a big part in the Romantic spell Père-Lachaise casts on visitors. Magnificent trees sprout from graves, consuming them one particle at a time. Ravenous roots and trunks bear up bits of stone, iron, or bone. The most astonishing sepulcher-devouring tree I know is an arm-span-wide purple beech on the Chemin du Dragon (in Division 27). Its gray, elephantine roots have been delving for decades into the Duhoulley family plot. They have obliterated at least one other tomb and are inching toward its neighbors.

If you fancy a frisson, take a look at the imposing sepulcher in Division 8 of Étienne Gaspard Robertson (1763–1837), a magician. Winged skulls, like demonic cherubs, perch at each corner of the massive tomb. Adepts of black masses swear the skulls swirl into the air with Robertson on moonless nights. In keeping with the symbolism of superstition, there are real, live feral cats and owls in many a ruined family chapel. Some nest in the boughs of ancient horse-chestnut trees. They scurry and flap in the twilight as they feed off the countless rodents that day-trippers seldom see. I have had the honor of seeing the rats and cats, owls and bats, having, on several occasions, been among the last visitors escorted out at nightfall.

Friends still ask me what it was like to work in an office practically in the cemetery’s back yard. I tell them the truth: I went to Père-Lachaise almost daily, to stroll and meditate, and I still cross Paris at least once a week to do the rounds of my favorite graves and monuments. In this Honoré de Balzac (buried in Division 48) is my mentor. In the 1810s and ’20s the sardonic novelist noted that he wandered among the tombs regularly to cheer himself up. It is cheering, in a way. I find nothing bizarre about eating lunch on a bench among the sepulchres when the weather is nice, for instance. But most people I know recoil at the thought of a picnic at Père-Lachaise.

Innocent picnicking is one thing, I retort. Scavenging for souvenirs is another. Just as visitors to Paris’s catacombs sometimes emerge with skulls or tibia tucked into their packs, a certain kind of souvenir-hunter combs Père-Lachaise searching for ceramic wreaths, stone heads, brass ornaments and, of course, bones. One egregious example of mindless souvenir hunting revolves around the cemetery’s most problematic resident: James Douglas Morrison, the “Jim” carved on scores of trees and tombs.

Jim was none other than the celebrated lead singer of the Doors, who died in Paris of a drug overdose in 1971. From the start his grave attracted attention, much of it unwelcome. However, not long after the release of Oliver Stone’s movie

The Doors

, the numbers of rowdy Jim-worshippers swelled into the thousands. Many vandalized Morrison’s and other, nearby tombs. Someone even managed to break off and steal Morrison’s stone bust, probably at night.

Why bother? For the same reasons the Grand Tour travelers of the eighteenth century looted the cemeteries of Rome, Naples, and Athens, perhaps. It may well be that for some benighted souls such trinkets represent a means of possessing the past, stopping time or climbing back through it to another age.

“One day these hills with their urns and epitaphs will be all that remains of our present generations and their subtle contrivances,” wrote a prescient Étienne Pivert de Senancour in the early 1800s. “They will compose, as Rome was said to do, a city of memories.”

In French the word

souvenir

indicates both objects and memories. Despite the eternal ambitions of the

concession à perpétuité

, though, nothing lasts forever, neither urns nor epitaphs nor even the memories associated with them. Who remembers Pivert de Senancour, for that matter, author of the deathless

Reveries sur la nature primitive de l’homme

, or fellow writer Benjamin Constant? Madame de Staël’s longtime lover, the acclaimed author of

Adolphe

and dozens of other works, Constant died fabulously famous in 1830, drawing one hundred thousand mourners to his funeral. Who remembers François Gémond, whose obelisk (in Division 25) is the tallest in Père-Lachaise? And what of Félix Beaujour (1765–1836)? His phallic stone tower in Division 48 rises from a rusticated stone drum to dizzying heights and is surely one of the world’s most astounding funerary monuments. The stones still stand but most of the men and women and their deeds have been forgotten.

Each year dozens of tombs collapse, exposing generations of coffins stacked vertically underneath. The roofs of chapels give way. Trees fall in storms, crushing tombstones and statuary. Iron rusts and stones flake into nothingness. Families, too, disappear. If the city authorities deem a tomb abandoned—usually because it is unsafe to passersby—its owners have three years to respond and make repairs. If they fail, the city revokes the concession, removes what remains of the tomb, and resells the land.

Eternity? The going price for a repossessed plot at Père-Lachaise is under ten thousand euros. That does not include work needed to make the site buildable, or, naturally, the cost of a monument. Private firms or family members must maintain the tombs and plots. The city of Paris merely sweeps and repairs the paved streets and gravel lanes, and plants the pansies or chrysanthemums in the cemetery’s many raised beds.

Death goes on, you might say, but then so does life. Among the monuments, oblivious children play. Lovers entwine on hidden paths, unwittingly reenacting the passion of Abélard and Héloïse. Elderly gentlemen sit in the sun, reading

Le Parisien, Le Monde

, or

Le Figaro

, while widows, always outnumbering them, polish the granite gravestones or feed the stray cats. And then of course there are the tourists, most of them clutching maps as they trip from tomb to tomb many, doubtless, wondering why they are here and what it all means in the grand scheme of things. Père-Lachaise is a lively city of the dead indeed and it’s likely to remain so, perhaps not for eternity, but for a long, long time.

François’s Follies: Building Afresh in a Museum City

The idea that Paris in a century or two could become the privileged enclave of Japanese tour operators is a thought that makes Mitterrand bristle

.

—L

UC

T

ESSIER

, Director of the Coordinating Body of the

Grands Projets

, 1988

haraoh,” “emperor,” and “king” were favorite titles given former president François Mitterrand. Admirers and detractors alike also called him “Tonton” for his avuncular charisma, or “La Grenouille,” because he looked startlingly like a frog. Mitterrand’s presidency lasted from 1981 to 1994. But his heritage as a builder lives on. Like a pharaoh, he commissioned a pyramid (at the Louvre) and a Great Library of Alexandria (the Très Grande Bibliothèque, at Tolbiac). With Napoleonic imperiousness he ordered a triumphal arch (at La Défense) and one-upped Napoléon III with a bigger opera house (at La Bastille). To prove he could subsume his presidential predecessor, he adopted the unfinished projects of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing: La Villette, the Musée d’Orsay, the Institut du Monde Arabe.

haraoh,” “emperor,” and “king” were favorite titles given former president François Mitterrand. Admirers and detractors alike also called him “Tonton” for his avuncular charisma, or “La Grenouille,” because he looked startlingly like a frog. Mitterrand’s presidency lasted from 1981 to 1994. But his heritage as a builder lives on. Like a pharaoh, he commissioned a pyramid (at the Louvre) and a Great Library of Alexandria (the Très Grande Bibliothèque, at Tolbiac). With Napoleonic imperiousness he ordered a triumphal arch (at La Défense) and one-upped Napoléon III with a bigger opera house (at La Bastille). To prove he could subsume his presidential predecessor, he adopted the unfinished projects of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing: La Villette, the Musée d’Orsay, the Institut du Monde Arabe.

Anyone who thinks Mitterrand’s so-called

Grands Projets

are old news should rethink: not only do Parisians have to live with them daily, a condition known by some as “collective sore eye.” The heritage of Mitterrand’s genius continues to gall into the current century. His international conference center planned for the Quai Branly near the Eiffel Tower only got under way after he died. His successor Jacques Chirac torpedoed the plan and commissioned the Quai Branly museum instead. A comic-strip supertanker or cargo ship with rust-red, canary yellow, and ochre shipping containers jutting from one side, the egregious complex excogitated by star-architect Jean Nouvel houses controversial African, Asian, and global multiethnic, multicultural collections. But this fiasco is not Tonton’s fault. His credits lies elsewhere.

With something approaching awe and horror I watched Mitterrand’s follies coalesce and had the good fortune to scramble through many while under construction, and interview their prime movers. Not long ago I revisited the president’s main offspring. Have they, as Mitterrand hoped, saved Paris from becoming a “museum city” cut off from its suburbs? Have they lastingly boosted the prestige of French architects, while indelibly impressing Mitterrand’s name in the history books?

Métro line 1 links the troika of sites that were closest to Mitterrand’s heart: Bastille, Louvre, Grande Arche. For the sake of chronology and convenience my first stop was the Louvre. Mitterrand’s earliest and most ambitious operation was transplant surgery on what had become a dusty, dreary place whose decline threatened Gallic

gloire

and

histoire

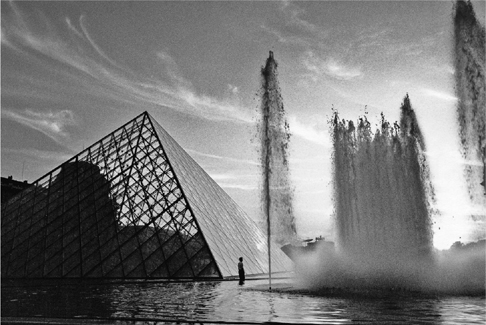

, not to mention tourism revenues. After visiting Washington’s National Gallery, Tonton highhandedly hired its designer I. M. Pei to create Le Grand Louvre. No architectural competition was held, a technical illegality. Mitterrand briefed Pei to respect the Louvre’s historic components. His solution was the now-familiar seventy-foot (twenty-two-meter) pyramid of glass and crisscrossed steel that rises above an underground entrance, theater, shopping concourse, and parking lots.

Like most Paris denizens, I was not thrilled by Pei’s proposal. But I recall my bafflement when critics claimed the pyramid would “deface” the Napoléon Courtyard’s façades. A historicist’s hodgepodge, they were as kitsch in their day as the pyramid was in the 1980s. In reality, at issue was the Socialist president’s perceived defiling of a royal enclave. As some pundits put it, Mitterrand marked it as a dog might.

Swept by crowds from the Métro station into the Louvre’s subterranean maw, I couldn’t help marveling now at Pei’s success in hitching high art to consumerism. Where the weary masses of old once deciphered turgid texts or strained their eyes on the museum’s badly displayed and unloved treasures (most of them looted in the days of earlier French kings and emperors), here were smiling hordes stuffed with exotic delicacies from the merry-go-round of Louvre restaurants, casting beatific glances at skillfully lit artworks before loading up on reproductions, CDs, designer sportswear, computers, and gadgets.

Pei’s entrance was conceived to simplify the Louvre’s labyrinth. Experts claim it takes less time than ever to reach the Mona Lisa (still the goal of ninety percent of visitors). Persnickety regulars at first grumbled about a crass Grand Louvre for beginners, and militated for a reopening of doors in the museum’s many wings. But they soon learned to slip in through the Pavillon de Flore, via whatever temporary exhibition is being mounted there, skipping the subterranean feeding frenzy.

Early on boosters said the pyramid would blend into the cityscape. They were right. As Pei predicted, the glass panes reflect changeable skies. They also collect soot, despite frequent scrubbings. Cosmetic concerns aside, I saw nary a grimace now as I shuffled with thousands from sculpture courts (where cars once parked) through restored Renaissance rooms and lavish Second Empire salons (formerly the Finance Minister’s office), to excavated medieval bastions. Back outside, I took a table at Café Marly and watched visitors dance in feathery water sprays or soak their feet in the fountains flanking the pyramid. Attendance has risen from 2.5 million in the early 1980s to nearly 9 million today. What better sign of approval might a monarch desire?