Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (10 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Alison tugged my hand. It was too hot to stand around waiting for a steam train that might never appear. We sought shade on the far side of a lake. A graceful suspension bridge spanned the greenish waters. Stone pinnacles shot up from the center of the lake. An airborne colonnaded temple nested atop one of them, at least a hundred feet above the groups of rowdy teenagers rowing in leaky boats around us. A waterfall rumbled in a grotto, setting mist adrift through gaps in the cliff face. A colorful kaleidoscope of neighborhood children played in channels of rushing water that spilled from rockeries. Sun-baked codgers pulled big, lazy bottom-feeders from the lake, dangled them in front of goggling toddlers, then tossed them back into the water. Swans and geese cruised by, honking and snapping at flotillas of stale bread. We cooled our heels in the shady stream, safely out of the swans’ reach, and Alison wondered out loud how many city kids and hot, tired adults like us had sought refuge in the park over the years.

I had a vague notion of the Buttes-Chaumont’s history, gleaned from park panels, guidebooks, and French literature. I knew, for example, that the site had been called

Chauve Mont

—bald mountain—because the gypsum and clay in the soil kept vegetation from growing, so that when it was turned into a park tons of horse manure and topsoil had to be brought in. I remembered that the same team of planners, architects, and designers who built Buttes-Chaumont worked their magic on the Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, Montsouris, and about two dozen city squares, at more or less the same time—the 1860s zenith of the Second Empire. Romantic English and exotic Asian gardens were in vogue then, and that would explain the park’s sinuous paths, I now reasoned, as well as the strategically positioned copses of trees and rock outcrops. Like anyone who’s read any French history, I’d come across stories, most of them inaccurate, of the

Gibet de Montfaucon

, a gallows built on a rise somewhere near here, where countless men and women were hanged from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance. And of course there were the tales of the bloody repression of the Communards, who fought the emperor’s counterrevolutionary Versaillais troops at Buttes-Chaumont in 1870, were slaughtered by them, and were buried or burned en masse on the Butte’s lawns.

But as we sat in the shade and dangled our feet in the stream the violence the park has known was nowhere to be seen, heard, or felt. Caged peacocks called from atop a grassy knoll, children squealed, teenagers exchanged bodily fluids, and I thought I caught the hissing of the old steam train echoing out of the cutting below Rue de la Crimée. But I was too dazed and content to climb the rise and have a look.

The heat, the summery garden scents, and the murmuring water lulled me into a state of reverie. That dazed sensation followed me home and, having engendered a powerful curiosity about the park, drove me to crack open several reference books on Paris, the Second Empire, and Buttes-Chaumont in particular. I soon discovered some curious facts. For instance, the park’s pinnacles were created to emulate the cliffs of Étretat, a favorite resort of the Second Empire’s upper classes (and of its painters, including Monet). My reference books also confirmed that the pinnacle-top temple is an exact replica of the Temple of Cybele in Tivoli, near Rome, dedicated to a goddess of the hearth. I learned that the suspension bridge stretches one hundred twenty feet across and thirty-five feet above the lake, and that the other, shorter bridge linking the temple to the park’s upper section is known as the Suicide Bridge. Jilted lovers long favored its tempting seventy-foot free-fall. Another nugget of information I came upon is that Gustave Eiffel built one of the park’s least remarkable bridges. As to statistics, various sources agree that amid the twenty five acres of lawn, the 3.2 miles of paved road, and 1.5 miles of winding paths, there are approximately 3,200 trees. My estimate would be that there are about thrice that many shrubs, something on the order of 10,000. Among the vegetation sprout many sculptures—some innocuous, some ludicrous—plus a hodgepodge of neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, Sino-English, and faux-Swiss park buildings typical of late-1800s eclecticism.

Though Baron Haussmann was in charge overall of the remake of Second Empire Paris, the real hero of its parks was Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand, an engineer and public works designer, flanked by landscaper Édouard André and architect Jean-Antoine-Gabriel Davioud. The big parks they created were linked by the ultramodern Petite Ceinture steam railway, and were conceived as more than mere rehab projects. The depleted quarries of Buttes-Chaumont, for example, had become the garbage dump of Belleville, to which the area then belonged, as well as an open-air slaughterhouse for horse-butchers, and the lair of murderers, robbers, and literary heroes like Arsène Lupin, the gentleman thief.

Ostensibly the reason Napoléon III commissioned his men to build Buttes-Chaumont, Montsouris, and the city’s other green spaces was the International Exposition of 1867. But these “democratic oases” as they were called were first and foremost an experiment in social engineering, what surrealist writer Louis Aragon in his bizarre book

Paris Peasant

called “artificial paradises.” The new parks of the brave new Paris were as essential as the

grands boulevards

, the train stations, and the smokestacks, thought Aragon and others. They were safety valves for the age of patriarchal capitalism, which depended on immigrant labor. Every leaf, every landscaped knoll and babbling watercourse was calculated to outdo Nature. By spending a few hours in the park, the theory went, the worker-bees of the empire, most of them transplanted French provincials or starveling Italians, would better bear the stress of the factory, the overcrowded city, the loss of beloved forests and fields. So, these soothing parklands were in reality tools of exploitation, an antirevolutionary opiate?

Buttes-Chaumont is only a half-hour’s walk across the Ménilmontant and Belleville neighborhoods from Père-Lachaise cemetery in northeastern Paris, one of my favorite stomping grounds. So, having satisfied my bookish curiosity about Napoléon III and his diabolical amusement parks, I took my usual cemetery stroll and eagerly trotted back to the Buttes to have another look. To me it is the most astonishing, picturesque, and alluring of the city’s artificial paradises. I wanted to view it again, with knowing eyes. Would this proto-Disneyland dreamed up by a dictator be as seductive now as I’d found it on earlier visits, when uninitiated into the emperor’s secrets?

“Let us stroll in this décor of desires, this décor filled with mental misdemeanors and with imaginary spasms,” wrote the playfully cryptic surrealist Aragon from the Buttes-Chaumont. “Décor” is the right word: as I stood again in the grotto near the thundering cascade I could see that the stalagmites were poured from cement, like the faux-wooden railings on the faux-stone pathways. But they were covered with fresh moss and seemed so worn and weathered that I couldn’t help finding them endearing.

From Cybele’s panoramic temple I took in the jumbled view, with Montmartre’s kitsch cupolas to the west and the housing projects of Pantin on the northeastern horizon. It was not a view calculated to please tourists, but I found it intriguing nonetheless, another example of social engineering, this one dreamed up by 1960s-’70s French president Georges Pompidou. Glancing down at the placid lake around the pinnacles’ base, I noticed in its ugly concrete bottom a tangle of water pipes.

Was the curtain being drawn back on the Wizard of Oz, I wondered ruefully?

Down the cast-concrete steps I clambered, through faux-caves, settling eventually on an old green bench near a garrulous group of fishermen.

“No, we do not catch sardines,” one of them quipped when I started to make conversation about the fishing. “We catch gudgeon, carp, and pike and we know some of them by name, like we know the swan, whose name is Jojo by the way.”

The fishermen chuckled at these apparently oft-recited lines. They knew the fish as well as they knew each other, they explained, because they bought them from a fish farm and stocked the lake yearly and were the only anglers legally entitled to dangle hooks for the bottom-feeders therein.

More artifice, I sighed, realizing that the poor dumb fish keep biting the same fishermen’s bait day in, day out, hooked and released, until the day they die of old age. But as I circled the lake on carefully plotted paths with temple-topped perspectives engineered to be dazzling whether glimpsed from high or low, and as I sipped a drink at the gimcrack café designed by a dictator’s minions, I felt a growing kinship not only with the duped immigrant workers of yesteryear who came here to rest up after their slave labors. The fact is I felt like the gudgeon, carp, or pike stocked by the fisherman. Maybe, I thought, sipping my coffee, maybe it’s precisely because Buttes-Chaumont, Montsouris, and the other Second Empire parks I love are so utterly artificial, so wantonly faux, that I’ll keep falling for their sepia-tinted charms hook, line, and sinker for as long as I live in Paris, the world capital of illusionism.

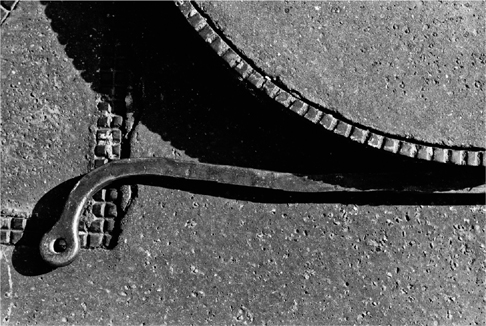

Going Underground

Through me you enter the city of pain

Through me you enter suffering eternal

Through me you go among lost souls …

—Engraved upon the gateway to Hell, D

ANTE

,

Inferno

t all started with two apparently unrelated subterranean events. The first was a routine damage-control visit to our basement—the

t all started with two apparently unrelated subterranean events. The first was a routine damage-control visit to our basement—the

cave

. Records indicate our Marais building got its façade in a 1784 remake of the neighborhood, near Saint-Paul’s, but that the structure dates to about 1630, with foundations and cellar from further back, poised atop the long-demolished priory of Sainte-Catherine-du-Val-des-Écoliers, founded in the thirteenth century.

You need a chopstick and a key to open our cellar door. Then you descend a steep, moldering staircase into centuries past, into the chalky, muddy underbelly of Paris—what Victor Hugo called “Lutetia, City of Mud,” a reference to the ancient Gallo-Roman city that stood here. I struck a match, sizzling cobwebs as I went, wrenched open the rotting wooden door to our section of cellar, and dug out a preindustrial candlestick holder. In the flickering candle flame I spotted a crack in the masonry I’d never noticed before. I could see nothing beyond, of course—the darkness was absolute. But I imagined an infernal world.

The main Roman road from Lutetia to Melun—nowadays Rue Saint-Antoine—runs a few hundred yards to the south of our building. The priory had stood here five hundred years, from twelve-something until the 1770s. Neighborhood oldtimers had told me of hidden passageways fanning from our cellar to catacombs, quarries, and long-gone fortresses.

“There’s another Paris under Paris,” intoned one neighbor, a paleontologist, echoing Hugo, the bard of buried Lutetia. The paleontologist’s words, recalled as I stood in our cellar, sent a pleasurable chill down my spine.

I snuffed my candle and plunged through a time tunnel into the Gallo-Roman city, then burrowed onward and upward to the malodorous Middle Ages, then to the days of Baron Haussmann and Jean Valjean (fugitive hero of Hugo’s

Les Misérables

), slowly resurfacing with Occupation-era French Resistance fighters and their underground networks, before clawing metaphorically back to the comforts of our banal present day. I re-lit the candle and dragged some suitably decomposed junk from the cellar to the garbage.

Not long after this first fantasy voyage, while strolling under the arcades of Place des Vosges near our building, I decided to step into a cluttered shop I’d passed a thousand times but had only visited twice. The affable owner, Pierre Balmès, a specialist in antique timepieces, reminded me that he’d opened for business in 1949. While moving in he had made a curious discovery. The square’s identical pavilions were built, he’d said, between 1605 and 1612—everyone knew that. But few realized Place des Vosges’s northern flank sits over the cellars of the Hôtel Royale des Tournelles, erected in 1388, destroyed in 1563 by order of Queen Catherine de Médicis. “I was sweeping the cellar floor,” Balmès recounted, “when I noticed what looked like a trap door …” The door led to another vaulted stone

cave

below it, choked with historical debris.