Paul Revere's Ride (62 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

One iconoclast of this new school was Richard Bissell, a dramatist whose credits included the popular broadway shows

The Pajama Game

and

Say, Darling.

In 1975 Bissell tried his hand at history. For the bicentennial celebration of the American Revolution he contributed a little book loosely modeled on 10

66 and All That,

called

New Light on 1776 and All That.

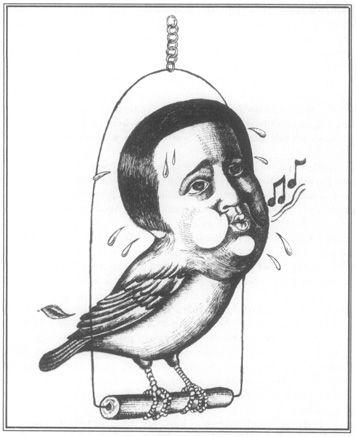

One of its chapters demolished the myth of Paul Revere and the battles of Lexington and Concord. Earlier iconoclasts had been content to accuse Paul Revere of failing to complete his ride, and stealing the glory from William Dawes and Samuel Prescott. Richard Bissell went further. He informed his readers that Paul Revere was a coward and traitor who “sang like a canary” to his British captors, and betrayed his friends to save his own skin. This interpretation was illustrated with a bizarre cartoon of Paul Revere as a canary, chirping away in his cage. Bissell’s account was grossly inaccurate, the very opposite of what actually happened; but it was what some Americans wanted to hear about their heroes.

48

A similar interpretation was repeated by a writer named John Train who in 1980 told a reporter for the

Washington Post

that Paul Revere “set out with two other guys for money … he was quite a despicable … he was arrested en route by the British. He turned stool pigeon and betrayed his two companions.” In fact Revere was not paid for his midnight ride, and in no way betrayed anyone. There was no truth whatever in these

interpretations, which combined credulity and cynicism in equal measure. But in the turbulent wake of Watergate and Vietnam, some Americans wanted desperately to disbelieve.

49

The iconoclasm that followed the Vietnam War was very different from the good-natured debunking of the 1920s. Several writers in the 1970s casually invented an accusation that Paul Revere’s Ride ended not merely in failure but in treason to his cause. One asserted that he “sang like a canary” to his British captors. As evidence, one iconoclast published this bizarre illustration to make his case. It was the opposite of what actually happened, but Americans in that unhappy era wanted desperately to disbelieve. (Little, Brown and Company)

In 1968, the editors of the

Boston Globe

joined in. That paper published an editorial on Patriots’ Day which roundly asserted as fact (with absolutely no evidence whatever) that early in the midnight ride Medford’s Captain Isaac Hall “gave Paul a little something to warm his bones,” and that it was “a little rum poured on top of patriotic fervor that caused Paul to sound his cry of alarm.” The only possible foundation for this idea was the fact that Captain Hall happened to own a distillery. There was nothing else in the record to support it, and much to the contrary about Revere as a man of temperate habits. But this schoolboy humor by the editors of the

Globe

was widely read and believed. Revere scholar Jayne Triber concludes that became “one source for the recent cynical belief that ‘Revere was drunk when he made the ride.’“

50

Iconoclasm became something of an industry in this period. A professional iconoclast

named Richard Shenkman was regularly employed by newspapers and television networks to explode the patriot myths of American history. In 1989 he captured the national mood in a book called

Legends, Lies and Cherished Myths of American History,

which included Paul Revere among its many targets. The author minimized the importance of the midnight ride, assuring its readers that Revere’s “role in warning of approaching redcoats has been exaggerated.” This work was followed by another volume called “I

Love Paul Revere, Whether He Rode or Not.”

The title, a garbled quotation from Warren Harding, hinted that maybe the midnight ride never actually happened at all. That innuendo was corrected inside the book, but once again bewildered students began to ask their teachers if it was true that Paul Revere never made his ride at all. From the work of the new iconoclasts, one could not be sure.

51

Filiopietists fought back. On April 19, 1975, in a bicentennial celebration of the American Revolution, the two parties confronted one another at Concord’s North Bridge. On one side was the official Revolutionary Bicentennial Commission led by President Gerald Ford, which celebrated Paul Revere and the minutemen as symbols of free enterprise and democracy On the other side was the People’s Bicentennial Commission, with Pete Seeger and Arlo Guthrie, who read (very selectively) from James Otis, Thomas Paine and Abigail Adams, and converted the occasion into an impassioned attack on American capitalism and multinational corporations. Altogether 100,000 people attended the event. The only damage was to the environment, from 822 tons of litter left by filiopietists and iconoclasts alike.

52

Something of the searing impact of the Vietnam War on historical memory in the United States appeared in an essay called “Ambush,” published by novelist and Vietnam veteran Tim O’Brien in 1993. The piece consisted of a series of passages on the fighting of April 19, 1775, alternating with the author’s highly personal memories of Vietnam. “The parallels,” O’Brien wrote, “struck me as both obvious and telling. A civil war. A powerful world-class army blundering through unfamiliar terrain. A myth of invincibility. Immense resources of wealth and firepower that somehow never produced definitive results. A sense of bewilderment and dislocation.”

This American identified mainly with the British Regulars, the grunts of an earlier war. “Down inside,” he added, “in some deeply human way, I had more in common with those long-dead redcoats than with the living men and women all around me. I felt a member of a mysterious old brotherhood: shared knowledge and shared terror. I could hear 700 pairs of boots on the road; I could smell the sweat and fear. Somewhere inside me, Vietnam and Battle Road seemed to merge into a single ghostly blur across history.”

What was most extraordinary in this work was its idea of history itself. “History was not made by plan or policy,” O’Brien asserted, “but by the biological forces of fatigue and fear and adrenaline.” He appeared to reject any idea of progress or purpose in human history. “What happens is this,” he insisted, “time puts on a fresh new uniform, revs up the firepower, calls itself progress.”

The author claimed a kinship with soldiers who came before him, but his essay was profoundly different from writings by veterans of earlier wars, including the men of Lexington and Concord whom he claimed as brothers in misfortune. The difference appeared not merely in the self-pity and despair of the Vietnam veteran, but in his profound rejection of any sort of teleology in history.

53

Academic History, Political Correctness, and Paul Revere

Academic History, Political Correctness, and Paul Revere

Parallel trends also appeared in changing patterns of professional scholarship. In the early 20th century, Paul Revere’s place in college textbooks had seemed secure. The academic historiography of that era centered on narrative sequences of political events. Paul Revere’s ride was given an important role as a device that connected one event to another. A case in point was Morison and Commager’s

Growth of the American Republic,

which represented,

Paul Revere’s ride as a major event that linked the coming of American revolution to the War of Independence. In an interpretation carefully balanced between Paul Revere and William Dawes, both figures appeared as heroic men on horseback who “aroused the whole countryside.” For any slow-witted sophomore who may have missed the point, both rides were dramatically plotted on a full-page map, with romantic silhouettes of galloping horses racing across the countryside.

54

After the generation of Morison and Commager, the dominant school of American historiography turned its attention from narratives of public events to analyses of intellectual systems and material structures—a change that reduced happenings such as Paul Revere’s ride to trivial incidents of no significance. Two of the leading college textbooks in this era,

The National Experience

(1962) and

The Great Republic

(1977), made no mention of Paul Revere’s ride whatever. The only published essay on the midnight ride in an historical journal during this period pronounced it to be a happening of “minor importance.”

55

A popular historian, Virginius Dabney, published a biographical history of the Revolution in which Paul Revere was deliberately omitted, and the midnight ride was dismissed as an event “of little or no importance.”

56

With the rise of the new social history, Paul Revere returned to the textbooks, but as a different character. The midnight rider was dismounted, and converted into a more pedestrian figure of one sort or another. Social historians variously represented him according, to their politics, as a Boston artisan, a bourgeois businessman, a leader of Boston’s “mechanic interest,” an active joiner of voluntary associations, or a producer of revolutionary propaganda. He became a figure of more complexity but less autonomy—not really an actor, but an exemplar of class movements and the organization of the means of production. There was no sense of contingency in these interpretations, and little recognition of individual agency. They rested on assumptions that individual actors in history are significant mainly as instruments of large processes over which they have little control. For the generation of Vietnam and Watergate, those organizing ideas became very strong in American universities.

57

Crosscurrents

Crosscurrents

Today attitudes are changing yet again, and interpretations of Paul Revere reflect the new mood. Levels of interest in various aspects of his career are stronger than ever before, and more diverse than in any earlier period. Many schools of interpretation compete with one another. Filiopietists are still out in force; celebrations of Patriots’ Day in Massachusetts are larger and more enthusiastic than ever before. More than a million tourists a year visit the North Bridge at Concord, and flock in growing numbers to Boston’s Freedom Trail. British travel writer Jack Crossley wrote after a visit to Boston, “You can also take a delightful hop-on-off trolley ride round the major attractions. The guide’s patter on these trips is a hoot. ‘You’ll hear a lot about Paul Revere on this ride. In fact you’ll get sick to death of his name, believe me.’ History is around every corner, and indeed Paul Revere is on most of them.”

58

At the same time, iconoclasts also continue to be very active, seeking to expose the underside of the American past. Many seem to be guides on Boston’s Freedom Trail, where they titillate the tourists by inventing new scandals about the midnight rider. The highly professional staff of the Paul Revere House was recently asked by a group of visitors if it was true, as their guide had told them, that Paul Revere had an affair with Mother Goose!

Many scholars are now busily at work, pursuing different lines of research on various aspects of Paul Revere’s life. A major study of Boston artisans is under way by Professor Alfred Young. A dissertation by Jayne Triber of Brown University is examining Revere’s republican principles. Specialists in material culture at the Winterthur Program and elsewhere have done much research on Revere’s silver, and on his business career. A catalogue by Morrison Heckscher and Leslie Bowman for an important exhibition at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art studies him as a highly inventive artist within the design tradition that they call American Rococo. Patrick Leehey, head of research at the Paul Revere House, is looking carefully into the Penobscot Expedition, the darkest episode in Revere’s life. Edith Steblecki has published an enlightening monograph on Revere and Freemasonry, a subject of growing interest to cultural historians. At the center of this activity is the Paul Revere Memorial Association, a flourishing organization that runs educational programs, awards fellowships to students, sponsors exhibitions, conducts an active publication program, serves as a clearing house for ongoing research, and welcomes more than 200,000 visitors each year to the Revere House in downtown Boston.

59