Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (15 page)

Read Percival Everett by Virgil Russell Online

Authors: Percival Everett

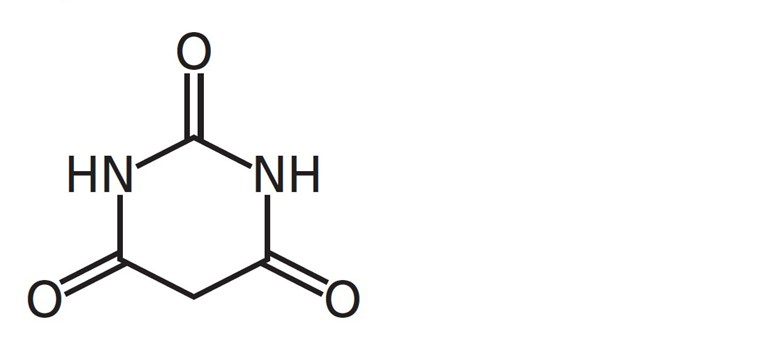

Sheldon Cohen was nonchalant as he browsed through the drugs closet. Usually he was ever so slightly fussy, if not on edge, but now, with me serving as sentry, in this space of vials, phials, ampoules, and bottles, he was completely at ease and in charge. He set the containers onto the counter and I stuffed them into my jacket pockets. Amytal, Seconal, Tuinal. He held a bottle close to his face. Ah, here we have it, Nembutal. And finally, Noveril and temazepam, that’s a nice cocktail for any occasion.

The moon was bright. Stealing the van was not difficult. Half the time they were left running in a parking lot down the hill from the central building, perhaps to keep them cool. I never knew. Regardless, the keys were nearly always either in the ignitions or stashed under the mats. Who would steal one of those beasts with a chairlift? Certainly not a joyriding teenager, unless he was highly imaginative. I started the vehicle and moved up the circular drive toward the front of our residence hall. It was more like steering a boat than driving a car, the back end caught in crosscurrents and eddies. I felt as if I were shouting the command to stop to my first officer and he to the helmsman when I stepped on the brake; however, I did manage to come to a halt near enough to the entrance. Mrs. Klink, Maria Cortez, and Sheldon Cohen came slowly out and filed into the van. I got out and went to Emily Kuratowski’s aid. She pushed herself out of her wheelchair and told me she would walk. Well, she couldn’t, but she was so tiny by this time that even at my age I was able to carry her. All seated, we drove off campus and west. And this is where, this is where, this is where, normally, you would get a detailed description of our journey and it might go something like this:

I had never seen the moon so huge. I drove toward it and it grew, as if we were drawing nearer. We sang songs, songs we knew, songs we didn’t. We sang:

My eyes are covered with sleep

I’ve walked through the years just fine.

Oh, I failed once or twice along the way,

But I got up every time.

The lights on the porches are dark

And no smoke from the chimneys rise.

Oh, the last time I checked my aching heart,

It was beating, to my surprise.

They let the dead bury the dead,

But they can’t because they’re decayed and blue.

Oh, the dead they are a lazy lot,

A hopeless, helpless crew.

We will live until we die,

Until then we’ll scribble some lines

About how the dead greet us every day

And remind us of our crimes.

We’ll listen with both ears.

We will watch them with both eyes.

Oh, the day their voices leave us alone

We’ll begin to realize

That puzzles come and go,

That children laugh and cry,

That nature abhors a vacuum

And every truth will spawn a lie.

And then maybe we would have a bus crash and it might sound like this:

Shibocraishcruncruncsqirpopchiksanpcunkicripfissssclnterterchichinkripdanfripbingchinriplashicrackripchikpoptapknicknocslithingkascrippopsicbangabingafrangakripknitficrashshebinbangboombinggingfeshcaripcrazingfacrinkacrashcringsnapsnasnasnasnappingcrumkarumvfuvfuvfuvfuvfuchinkfuck

But none of that here. We made it to Malibu and Point Dume. We even made it to the beach at the base of the promontory. I carried Emily Kuratowski. She seemed even lighter that time. We looked out over Santa Monica Bay, at the lights, at the water, at the moon, but mostly at each other. I might have been the only one who experienced an inkling of reluctance or irresolution, but it was only an inkling and I soon learned how small that unit is as it disappeared with one line from Emily.

I don’t have to take the potion, I’m sitting on the sand at the beach.

I took the urn of Billy’s ashes from the sack that Sheldon had carried for me and sat it with us.

This where normally you might get a lot of touching and sentimental language and portentous dialogue, but I don’t think so. We took our medicine and then we sat with ashes.

A

Coma, coma, coma,

That’s what I’m in, that’s what I’m in.

Coma, coma, coma,

That’s what I’m in today!

Torpor, torpor, torpor,

That’s what I feel, that’s what I feel.

Torpor, torpor, torpor,

That’s what I feel today!

The great, splendid, useful thing about a character in a coma is that he can say just about anything. But why would he want to?

You’re not in a coma.

Says you.

Here’s what it looks like where I am right now:

I've always wanted to see this place. I can see there's a river down there. I wonder if it's deep. Probably fast in places. I'm angry with my education. I wish I could have come upon this landscape until I paused and shook my head and wondered, what is that ahead of me? Imagine the marvel of it.

It’s beautiful wherever I look. I suppose that’s to be expected. Or maybe not. What does it mean, this being beautiful? Is it really in the eye of the so-called beholder? Is it beautiful because of what it is or because of what it was? Is it beautiful to me because it speaks to age, to the passage of rivers and time and the erosion of so much? I could argue all day with an idiot who does not find this landscape beautiful, but even he can point to no place in it that is ugly, where I find it unpleasant to fix his gaze. Except perhaps for that one cloud, you see the one I mean. That one there. Yes. It might be a cirrus. What do I know from clouds? It might be a forming thunderhead. It might be the beard of god or one of the gods, the genital hair of the devil. What I love is that the distance is so distant. One can see all the way till one stops seeing, till it’s dark, till the matter falls into other hands. There are more shadows than you can count, should one be a shadow counter, reckoning ghosts and totting up silhouettes, making a mark for each one in a little book attached to your belt by a string. Is it early or late? How sad to be late. Sadder to be late early. How wonderful to be late late. There is no vagueness, though nothing is distinct, a well-defined place with no definition. Pass the bottle. A bottle for me. A bottle for you. I’m taking a nap. I am just now letting myself go, with the lassitude produced by one disheartening, dispiriting evening of bad weather after another. Again, I would close my eyes if they weren’t already shut. From this moment on I cannot open or shut my eyes. Hang me in a museum and I will be happy. Hang me in a mausoleum and I won’t know the difference. Help me paint the charnel house, the charnel house, the charnel house. Help me paint the charnel house that’s out on Drury Lane. Call this a profound state of unconsciousness. I cannot (or will not) be awakened, I do not respond to light (seems I never did), I do not have sleep-wake cycles (no such thing), and I do not produce voluntary actions (a matter open to debate). How romantic, this language about the depth of my depth, somewhere between here and Glasgow. They say I’m a ten. I don’t know whether that is good or bad, but I know that it is irrelevant. I think I’ll move a finger just to fuck with them. If I could get up and walk to the window, I would. If I could be fidgety and not remain fixed, I would. If I could stand over there and observe the fine rain that I heard someone mention, I would. The rain will stop soon. Then there will be a sweet sunset to which I will not bear witness, a sweet sunset, twilight, evening. A waning moon and it will rise toward midnight. And some words are so familiar. Here, at this juncture, I might recall the gaps in my stories or the gaps in your stories or I might realize, as I do, that the gaps are the stories and that I should stop trying to leap over them and instead into them, the gaps. By the way, burn me up when the time comes. That patch of ground is no patch at all; it covers nothing. That plot is nothing but another gap that gets filled in by itself. I’ll be dead and so it will never be my plot, in part or whole. My brother was buried in one and it did him no good, did his children no good. They still pay him visits, like morons. Even his pretty wife continued to stop by his plot and retell his story, the parts she knew, the parts she remembered, until she too moved in beside him. He was only a moderately good man or so I understood from all reports. I did not know him well; that made him a decent brother. Still, he never stole anything from me, never betrayed me, never even hurt my fragile feelings. He never invited me to his grave, his plot. He never had the language he needed. I always had too much, maybe. Perhaps I only talked too much. Wending my way through words to find a plot worthy of either digging up or filling in, isn’t that what it was all about? I probably would have nothing but truly fond feelings for my brother had he not had such success with his one book. He was a bibliographer. Someone has to do it, he would always say of his work, and he wrote a book that remains in print,

Famous Lines from Obscure Books.

I hated that book and I hated that he put a line from me in it. That I no doubt belonged in it was beside the point and it didn’t sweeten the pot that he had acted in sober and diligent sincerity. The line occurs near the end of my

Pass the Joint, Motherfucker;

an extremely high character slaps his forehead and says,

Oh, that’s what

epiphany

means.

Had he included me to poke me a little, to needle me, to annoy me, I could have easily forgiven him, and what’s more I would have found him a more interesting person. He was what he was, uncomplicated, undemanding, somewhat unassuming though he was a bit pretentious, guileless (not at all a bad thing), and decent. He was completely unlike his brother, who would probably have fucked his French wife if given half a chance. One Thanksgiving in Iowa City, I did have half a chance. My wife had just come back from Canada and her fling with the flying boy, though she didn’t know I knew, but I knew I knew and that was bad enough, and so our house was filled with tension and Irish whisky. It was typically and brutally cold that Thanksgiving. Anne-Charlotte being from Nice did not like the weather and pretty much refused to leave the house. I walked into the bathroom while she was just stepping out of the shower. I froze, staring at her. She was beautiful and, in her French way, knew it. Excusez-moi pendant que je me sécher, she said, but really wasn’t asking me to leave. I felt like a hippopotamus in a canoe. I flatter myself thinking that she might have been willing to kiss me, but, regardless, I never found out. I backed out of the room like a coward, felt guilty for a few seconds, then thought to myself that she was worth seeing. My impure thoughts, if I actually had them, were apparently enough to let me feel even with my decent, bibliographical brother and nearly square with my indecent, flyboyloving wife. It had been nice of my brother to come visit, though a surprise, as I was not the most pleasant person and certainly not a pleasant brother. When he arrived, I asked, Why did you come to Iowa City? He replied, Because this is where you live. Again, without a hint of irony or even an appreciation of his question begging. One night, after dinner, while we sat alone at the kitchen table drinking tea and Irish whisky, he asked me if writers were like composers. I, for one of the few times in my life, did not answer immediately but stared at my tea, in particular at a bit of leaf floating near the far rim. Finally, I said, No, we have no math. We cannot divide our words in half and achieve predictable tones. We have no relative minors. We have no circle of fifths, except for the ones we drink. As much as there is magic in music, what we make comes only out of magic. I was a little drunk, I realized. The tones of music are the tones, an A is an A, a B-flat a B-flat. But what is a ball? What is a game? What is a hell? This is kind of a hell, isn’t it? Having to sit here and listen to me. He sipped his whisky. Why do you ask? I wanted to know. He said it was because he had just remembered how our notebooks were called composition books when we were kids. I drank all of my whisky and stared into his face. He could have offered no answer that was as beautiful or as sublimely disappointing. And as earnest as a whale’s song or baby’s cry. My brother was not without real faults to accompany the petty ones I chose to attribute to him. He was an alcoholic for much of his life and he claimed for a while that it was a disease and asked if I could be a little more compassionate and then he told me one extremely hot July night at his place in DC that he wasn’t suffering from a disease at all, but that he really liked to drink and that was apparently not good for his relationships. Or your liver, I added. This from the man who wrote

Pass the Joint, Motherfucker,

he said. It wasn’t about drugs, I said, somewhat stupidly. He laughed. Then he stopped drinking, whether it was cold turkey (his stopping) I don’t know, but of a sudden he no longer had that sour smell, that idiotic glaze on his eyes. He was sober and to his credit he was sober without a god. He was more like he was before drink and this was good and bad. To say that I did not love my brother would have been not altogether true. In fact, I envied him. He saw a beautiful world. It was a fault, but an honest one. It was this childish disposition and my disdain for the optimism and hopefulness that provided me with the conceit that art must arise through suffering. Perhaps because of my own shortcomings, this manifested in my seeking to create that suffering in those in my circuit of life. My sin as a cynic was to take myself seriously. And so I pray you, by that virtue that leads you to the topmost of the stairs, be mindful in due time of my pain. Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina. Into the fire that refines. But do not take me too seriously, for I could not take that. Thank god there is no religion in my life, the fire notwithstanding. I noticed some time ago the disappearance of the sin of simony. So many Simon Magi about, I suppose. One could come in here now and lay hands on me and I’d twitch a toe or get an erection and make his career. But there will no wood showing in these parts. That’s okay. I remember sex and I remember it fondly, but I cannot recall any singular sensation of any distinct and particular, discrete even, moment of the sex itself. I recall only the air around it, whether I was happy or sad, peaceful or distracted, falling into or out of love, the excitement of anticipation, disappointment. I can talk myself into imagining that I remember especially fine orgasms, but I think that’s all delusion, like rehearsed memories of childhood. I know I loved sex, but I believe what I miss is the touching, the movement, the air around it, like I said. The fire notwithstanding. I have these nurses. I know their names from their chatting with each other. There are three women and two men and they are, I believe, kind to me. Emilia, Lauretta, and Elissa see to me during the day and overnight my bags are emptied by Pan and Dion. They are my Pentameron and I listen to them tell their stories every night. They all speak to me, but only one question is common between them. They ask, to a person, Is there anyone in there? I answer, Yes, we are here, we are here. All of us are in here. Nat is still working away on his confessions of Billy Styron, specifically the part where young Billy spies the poor young black daughter of his family’s maid and he thinks that she is like bubbles floating in an immediate effulgence of perfection and maybe purity, watching her pause to look up from her work and let her slender brown fingers pass lightly over her damp brow, but at any rate she fills him with a raw kind of hunger, which he chooses to see as a refined, cultivated lust, a well-mannered biological urge. Finally, he pins her behind the foaling shed and

talks

her into having sex with him, but he can’t get it up and so he is left to masturbate. It’s only fair, Nat says, it’s only fair that I too get to tell what is true, what is true, the bison’s in the meadow, the elephant’s in the zoo. And Murphy and Lang, we’re all in here, in all our various time zones and dress and dementias. And I am here, too, refusing to, as my father put it, cram for finals. No holy ghost for me, no accepting this one as my lord and savior, my guide and bookie, my plumber and electrician, and what the fuck does that even mean? My savior? Isn’t it amazing how many questions one manufactures when in a vegetative state? Other than Texas.