Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (22 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

The work produced Delaware Avenue, a proper street twenty-five feet wide and paved with Belgian blocks between Vine and South Streets. Girard's money also led to the construction of bulkheads and the first lighting along the river (first with gas lamps, later with arc lamps). The City of Philadelphia expended $249,696.81 of Girard's legacy.

With Delaware Avenue so close to the water, the bowsprits and booms of ships sometimes extended over to storehouses on the avenue's west side. This is much like how parts of the front of vessels at James West's shipyard would reach over Water Street one hundred years earlier.

Commerce increased rapidly, and the city had to undertake the second widening of Delaware Avenue from 1857 to 1867, this time to fifty feet. The work expended $313,726.30 from Girard's Delaware Avenue Fund. The avenue was also extended north of Vine and south of South Street in the 1870s and successively afterward.

Traffic tie-ups continued to increase, a state of affairs that often delayed shippers who hauled perishable goods. So additional widening occurred from 1897 to 1900, when Delaware Avenue was broadened to 150 feet. This street became the widest and longest riverside avenue in the world.

The 1890s work was the most expensive civic improvement project in Philadelphia up to that time. Wharf owners were, of course, compensated for their property and buildings, as they had been during earlier widenings of Delaware Avenue.

A new concrete bulkhead line was also constructed for a mile alongside the river to allow for larger and more up-to-date shipping terminals. Today's bulkhead line basically follows the one that the U.S. secretary of war established on the east side of Delaware Avenue at that time. The line was last modified on September 10, 1940 (33 U.S.C. § 59j).

Work is underway in 1899 to widen Delaware Avenue. This view is looking north from Chestnut Street. Notice the Philadelphia Cold Storage Warehouse in the distanceâthe only building in this image still around.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

P

AUL

B

ECK

'

S

P

LANS FOR THE

C

ENTRAL

W

ATERFRONT

Stephen Girard was not the first to propose bettering Philadelphia's riverfront. In 1820, Paul Beck Jr. (1757â1844) prepared a plan for improving the river's edge between Vine and Spruce Streets. This was the first urban planning exercise in Philadelphia after the laying out of the city itself.

Beck's scheme was for the municipal government to acquire all property from Vine to Spruce Street east of Front Street and then clear away all extant buildings, wharves, streets, steps and so forth. A series of uniform warehouses would be built between Front Street and a wide new avenue by the Delaware. Each warehouse would stand on its own forty- by one-hundred-foot block, separated by alleys. These improvements were estimated to cost $3,651,000âan astronomical sum back then.

The Beck-Care Warehouse at 18â20 South Delaware Avenue, erected in the late eighteenth century by Paul Beck. From 1860 to 1954, the building was the headquarters of a fertilizer maker. When it was demolished for I-95 in 1967, this was the last surviving eighteenth-century warehouse on the Philadelphia waterfront.

Library of Congress (HABS)

.

Paul Beck submitted his plan to Stephen Girard for his opinion, but Girard curiously opposed it. Yet it surely must have suggested to Girard that giving Philadelphia money to develop the central Delaware frontage would help the city immensely.

Remarkably similar, Girard and Beck were virtual waterfront successors to Benjamin Franklin and Philip Syng. Like Girard, Paul Beck was an importer/exporter, having acquired a fortune in the wine trade (yet another millionaire by the water). Beck, like Girard, was a port warden of Philadelphia who was intimately familiar with the city waterfront. Beck's “counting house” was at Front and Market, and he owned storehouses along the Delaware. (One located between Market and Chestnut Streets stood until the 1960s.) And like Girard, Beck chose to live and work on Philadelphia's riverfront despite its history of dirtiness and disease, and despite being wealthy enough to live elsewhere.

S

MITH

'

S

AND

W

INDMILL

I

SLANDS

To accommodate the last round of Delaware Avenue widening, a set of narrow islands in the middle of the Delaware River had to be removed. These isles were opposite Philadelphia's wharves, more or less between Market and South Streets.

The two islands had previously been one long isle called Windmill Island, roughly twenty-five acres in size. This land mass was a type of made-earthâthe result of accumulated sand and silt carried downriver by ice and spring floods on the Delaware. Windmill Island was not a fixed place, as it washed away at one end as fast as it grew at another. Its name arose from an octagonal windmill at its northern end, assembled in 1746 by one John Harding.

At various times, it was proposed to bridge the channel and to use Windmill Island as a midway point. These plans were opposed by those who foresaw that the island would have to be dredged away someday.

In 1782, a man named Thomas Wilkinson was hanged for piracy on Windmill Island, leading to fanciful stories that the place was a haven for pirates. Other confirmed pirates were hanged there, so the stories may be true. Early murderers of Philadelphia were also taken to Windmill Island for execution.

The Camden and Philadelphia Ferry had its route between Philadelphia's Walnut Street and Camden's Federal Street. The firm was tired of steaming its ferryboats around the isle since the persistent detour added cost to each ferry trip in terms of time and fuel. So it cut a canal across Windmill Island about 1838. (The DRWC's RiverLink Ferry crosses the channel nowadays exactly where this cut used to be.) The canal in effect created two islands: Windmill Island on the south and Smith's Island, somewhat smaller, on the north.

Smith's Island was named after a John Smith who had owned the northern half of Windmill Island and lived there with his family. Willow trees were planted and flourished on Smith's Island. Then, parks, restaurants, lodges and bathing resorts were constructed on it. Floating baths within the Delaware River had operated there as early as 1826.

In the 1880s, Jacob Ridgway built an amusement park on Smith's Island. (This was likely the same man who owned the Ridgway House Hotel.) Ridgway Park became a popular place for Philadelphians to spend a day of frolickingâ“mostly for the lower classes” who lived near the docks, as one author wrote. Hot-air balloon ascensions or tightrope walkers would sometimes entertain visitors. The beer garden at Ridgway Park was especially well patronized. Steam ferries crammed with day-trippers left the Walnut Street Wharf every ten minutes.

Windmill Island, meanwhile, supported a lead works, a dye works and coal boat wharves. A charitable resort for sick and underprivileged children was also there starting in 1877. Chartered boats would pick up kids and their parents from congested Philadelphia neighborhoods all along the Delaware frontage. They were taken to Windmill Island to enjoy a day of recreation, fresh air and free bowls of hot soup with crackers.

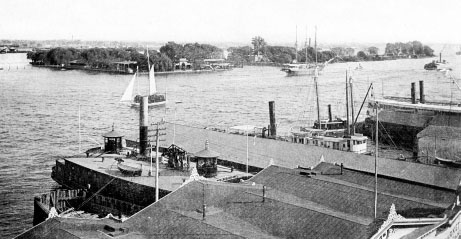

Smith's and Windmill Islands on the Delaware, prior to 1894 and their subsequent removal.

Adam Levine Collection

.

The resort, which became nicknamed “Soupy Island,” moved to Red Bank, New Jersey, in 1886. The Sanitarium Playground of New Jersey is there to this day, still offering summertime funâand hot soupâto hundreds of inner-city children of eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey.

The federal government cleared away both Windmill and Smith's Islands in the 1890s. Shipping interests had campaigned to eliminate the landmasses beginning in 1874, calling them impediments to cargo-laden vessels on the river. Plus, the U.S. government wanted a six-hundred-foot-wide shipping channel in the Delaware by then.

Work to remove the islands began in earnest in 1893 and was completed by 1897. The river along the Philadelphia front was also dredged for the first of several times since then. The twenty-six-foot-deep channel was near the center (but closer to Philadelphia) of the pre-existing nineteen-hundred-foot-wide channel between the Philadelphia and Camden pier heads. (The Delaware is much shallower on the Camden side.) The shipping channel is now forty feet deep in the Philadelphia region, but efforts are underway to dredge the river to forty-five feet.

With Windmill and Smith's Islands gone and the channel enlarged as needed, Delaware Avenue could then be made 150 feet wide, and longer replacement docks could be built out into the river as far as 650 feet (but usually not that long). About a dozen new finger piers were built in the ten years following 1897. They were considered vital to Philadelphia's commercial development, since the piers they replaced were too short for vessels being built at that time.

The removal of these islands is an instance of the commercial use of the Delaware taking precedence over preexisting recreational uses. Their elimination to redouble the river's shipping utility presages another mammoth federal transportationârelated project about seventy years later: the routing of I-95 through the Philadelphia waterfront. Both projects were the respective superhighways of their day. And fundamentally, they were both implemented to speed commercial traffic through Philadelphia, be it ships and barges or cars and trucks.

T

HE

B

ELT

L

INE

R

AILROAD

Besides providing access to ferries linking Philadelphia to Camden and other New Jersey river towns, Delaware Avenue was the primary transportation corridor for the shipping and handling of food and general cargo for the entire city during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. All early photographs of the thoroughfare show a horde of horse-drawn wagons jamming the street. The situation didn't change when motorized trucks took over.

Two sets of railroad tracks ran on Delaware Avenue since the 1890s to meet the freight hauling needs of the docks and industries along the river, with siding tracks connecting to various facilities on both sides of the avenue. Known as the Philadelphia Belt Line Railroad, these tracks ran about eighteen miles from Port Richmond to South Philadelphia.

The Belt Line Railroad was chartered in 1889 and was jointly operated by the three trunk railroadsâthe Pennsylvania, the Reading and the Baltimore & Ohioâthat served Philadelphia during its industrial heyday. The line enabled the efficient moving of merchandise to and from the central waterfront.

Many Philadelphians remember how the Belt Line's tracks and the street's crumbling Belgian-block surface made automobile travel on Delaware Avenue perilous for years and years. Not only that, but wagons and motor vehicles also had to share the jarringly bumpy road with steam locomotives pushing and pulling boxcars.

The Philadelphia Belt Line was never an operating railroad, although it did have track and maintenance equipment and employees. It still existsâchiefly a real estate holding companyâand its tracks are still active in South Philadelphia. One set of seldom-used tracks remains in a separate right of way in the middle of Delaware Avenue up to Race Street.