Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (23 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

P

ENN

'

S

L

ANDING

T

ROLLEY

There is talk of using these tracks for a $500 million light-rail line on Delaware Avenue. It would be more for tourists than commuters, but this is nothing new.

From 1982 to 1995, a private group called the Buckingham Valley Trolley Association ran a tourist-oriented trolley service on a one-mile stretch of Belt Line tracks. Volunteers of the Penn's Landing Trolley operated three or four historic trolleys every day during the tourist season. The trolleys ran between the Ben Franklin Bridge and South Philadelphia, making stops at major intersections on Delaware Avenue.

Ridership peaked in 1987. Then, pedestrian ramps over Market, Chestnut and Walnut Streets were completed, diverting foot traffic from Columbus Boulevard (Delaware Avenue). The city government also lost its enthusiasm for trolleys as other activities at Penn's Landing moved to the forefront. The Penn's Landing Trolley shut down in 1995, and the trolley fleet went to the Electric City Trolley Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

“G

OODISVILLE

”

Delaware Avenue featured many bars for sailors and stevedores in the early years of the 1900s. Some of them were welcoming establishments where men could take a break from manual labor and escape the crowded living conditions of ships and boardinghouses. Others were bawdy places to which sailors would run as soon as they received shore leave.

Some of these taverns doubled as houses of ill repute and contributed to the drunkenness, crime and prostitution that infested sections of the Delaware waterfront. A few bar owners raised fighting dogs and roosters for underground gambling action. As the river was prone to flooding Delaware Avenue, dockworkers could earn free booze by helping bail out saloon cellars. (The Delaware still floods the street now and then.)

It was in this seedy port district that 1950s and '60s paperback author David Goodis (1917â1967) set most of his bleak crime novels. In the essay “David Goodis's Hardboiled Philadelphia,” cultural historian Jay Gertzman gave a name to the grimy old waterfront: “Goodisville.” It was a tired industrial area of broken paving stones and worn railroad tracks, populated by flophouses, taverns and diners amid decaying warehouses and piers. Philadelphia's Tenderloin (Skid Row) was to the immediate east, above and including the Old City and Callowhill neighborhoods.

The demise of Goodisville, for good or bad, took about twenty years, beginning in the late 1950s. Southwark was cleared for the Interstate, Society Hill was redeveloped and the once-thriving but then-dying central waterfront was remade as Penn's Landing. Urban pioneers, restaurateurs and night clubbers arrived. Hardworking Delaware Avenue became haughty Columbus Boulevard. By the 1980s, Goodisville was finished.

Even so, a 1990

Philadelphia Inquirer

editorial on Delaware Avenue declared, “The roadway is so damn ugly, decrepit and dangerous no one would want to be anywhere near it.”

D

ELAWARE

A

VENUE VERSUS

C

OLUMBUS

B

OULEVARD

In 1992, the Italian community of South Philadelphia persuaded Philadelphia City Council to celebrate the 500

th

anniversary of Christopher Columbus sailing to America by renaming Delaware Avenue after the explorer. Citizens in the northern precincts of the city, aided by members of the local Lenni-Lenape tribe, fought the name change. A compromise was reached in which the avenue was renamed only south of Spring Garden Street. Nevertheless, street signs reading “C Columbus Blvd” were defaced for years after.

Christopher Columbus did get something else: the

Columbus Monument

at Penn's Landing, facing Dock Street. This three-sided stainless steel obelisk commemorates Columbus's 1492 voyage and the role that immigrants have played in developing Philadelphia and the United States. Designed by world-renowned architect Robert Venturi, the Columbus Monument was installed in 1992 and rises 106 feet.

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania paved and landscaped Delaware Avenue in the 1990s. Instead of a rough stone roadway filled with ruts, rats and railroad tracks, the street is now smooth, well lit and ornamented with greenery. Columbus Boulevard is, indeed, a fulfillment of Stephen Girard's desire for a wide, tree-lined thoroughfare along the Delaware.

T

HE

P

ORT OF

P

HILADELPHIA

T

ODAY

The tough longshoremen of Goodisville were mostly a memory by the 1970s, as containerization and highway-based shipping had made the original Philadelphia port obsolete. The city's cargo-handling operations by then had moved to more spacious port facilities along the Delaware River.

Most Philadelphia-bound cargo ships dock primarily at the quay-type piers at the 112-acre Packer Avenue Marine Terminal south of Snyder Avenue in South Philadelphia. Others head to the 116-acre Tioga Marine Terminal far north of the city's original waterfront. Both of these facilities were built in the 1970s by the Philadelphia Port Corporation, a nonprofit, quasi-public port agency established in 1965 to replace the Department of Wharves, Docks and Ferries.

Just a handful of workers are needed at these terminals to operate overhead cranes that unload containers stuffed with cargo from around the world. (These massive gantry cranes are a bit more powerful than the “fine necessary Crane” on Samuel Carpenter's Wharf.) All this goes on behind barbed wire and chain-link fences. This is a far cry from when visitors would drop by Joshua Humphreys' shipyard for a firsthand look at naval vessels being constructed or when prostitutes used to prowl the busy docks and markets along the Delaware.

A 1930s WPA poster.

Library of Congress

.

These days, the Port of Philadelphia is among the largest freshwater ports in the world and one of the most active in the United States. It's the largest port of entry for produce in the United States and the nation's chief break-bulk port. It is also the fourth-largest port for processing imported goods in the country and the only American port serviced by three railroads. And Interstate 95 is, of course, nearby.

The Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, created in 1990 as an independent agency of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, manages Philadelphia's cargo piers and terminals today. The authority's mission statement includes this: “Nothing is more important than protecting the Port of Philadelphia's 300-plus year legacy as a major center of maritime industrial commerce.”

19

P

ENN

'

S

L

ANDING

F

ESTIVITIES AND

T

RAGEDIES ON THE

W

ATER

Penn's Landing is so named, obviously, because of its proximity to where William Penn first entered the future city of Philadelphia and to honor this event.

G

ENESIS OF THE

M

ODERN

W

ATERFRONT

The old cargo and passenger piers along Delaware Avenue had become decrepit by the mid-twentieth century. Only six of the twenty-three piers along the waterfront were still in use for waterborne commerce by 1956. Once the foundation of Philadelphia's commercial development and strength, the downtown docks had become outmoded and a blight to the city. Some of the old piers, vacated one by one, suffered fires that destroyed them. Others, mainly those between Market and South Streets, were removed or filled in to create the recreational area known as Penn's Landing.

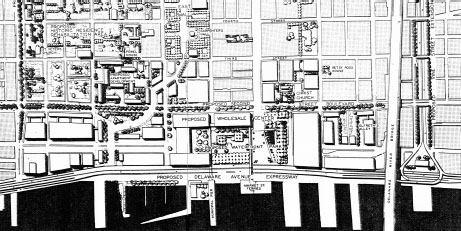

The germ of Penn's Landing can be traced back to December 1947. This is when the Philadelphia City Planning Commission released its

Preliminary Plan for Old City Area

as part of the Better Philadelphia Expedition. An illustration showed a marina between Chestnut and Spruce Streets, a large wholesale center surrounding a waterfront park between Market and Chestnut Streets, and an expressway taking the place of Delaware Avenue.

Then, in late 1951, Thomas Brown, director of the Department of Wharves, Docks and Ferries, proposed creating a “small and attractive yacht basin and a large recreation pier which visitors will remember” on the site of the derelict piers then between Market and Chestnut Streets. Brown observed that the condition of these docksâmost owned by the Pennsylvania Railroadâdid “nothing to enhance the appearance of [the] waterfront.” The modest plan was contingent on the railroad abandoning its ferry and freight operations in that area, which it did in 1952.

The first incarnation of Penn's Landing.

From the Philadelphia City Planning Commission's 1947 Preliminary Plan for Old City Area

.

However, Penn's Landing, as it ultimately became, was envisioned in the 1950s and '60s by Edmund Bacon (1910â2005), head planner and executive director at the Philadelphia Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970. He based his plan on the 1947

Preliminary Plan

and his underlying conviction that publicly financed improvements would stimulate private investment in Philadelphia's downtown waterfront.

The architectural firm Geddes Brecher Qualls Cunningham issued the first true master plan for Penn's Landing in 1963 on behalf of the Planning Commission. The prologue of

Penn's Landing: A Master Plan for Philadelphia's Downtown Waterfront

states:

The City of Philadelphia has acquired the waterfront properties in this nautical mile and has prepared a comprehensive master plan designed to realize its full historic, aesthetic and commercial potential. A careful balance will be maintained between public and private investment throughout the two main stages of constructionâso that the direct income from privately financed elements and indirect (tax-generated) income from publicly financed elements will support the high standards of design and operation essential at this key location

.

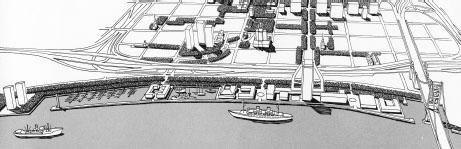

An early drawing of Penn's Landing. Note the unbuilt Crosstown Expressway (I-695) on the left. Note also the mirror image of Penn's Landing as plannedâonly the southern portion was built.

From

Penn's Landing: A Master Plan

(1963)

.

The plan included a recreational wharf at Dock Street, a boat basin, a maritime museum and a “Port Tower” at the base of Market Street. To put this all into effect, Mayor James Tate, in 1970, set up the Penn's Landing Corporation as a subsidiary of the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation.

C

ONSTRUCTION

B

EGINS

!

The first of the rotting ferry landings and wharves to be demolished in the late 1950s were those of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Actual construction of Penn's Landing began in 1967. The segment between Market and South Streets was constructed on landfill (made-earth) in preparation for the U.S. Bicentennial. This first phase of the project consisted of a marina and a protective breakwater with a promenade on top.

Penn's Landing was designed to mirror itself: a comparable breakwater and marina were to be built north of Market Street. If this phase of the project had been completed, Piers 3 and 5 would have been demolished, as would Piers 9 and 11. But only half of Penn's Landing was finished due to the lack of both public funds and private investment. There's certainly no intention of ever carrying out the full design, especially with the condo communities of Piers 3 and 5 in the way.