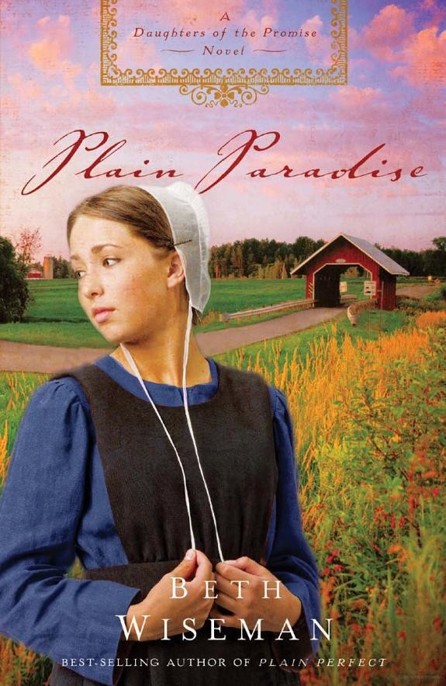

Plain Paradise

Authors: Beth Wiseman

Tags: #Fiction, #Christian, #Romance, #ebook, #book

Plain Paradise

Other Novels by Beth Wiseman Include:

Plain Promise

Plain Pursuit

Plain Perfect

Amish novellas found in:

An Amish Gathering

An Amish Christmas

Plain Paradise

A Daughters of the Promise Novel

B

ETH

W

ISEMAN

© 2009 by Beth Wiseman

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Publisher’s Note: This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. All characters are fictional, and any similarity to people living or dead is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-159554-823-8

Printed in the United States of America

10 11 12 13 14 RRD 5 4 3 2 1

To Barbie Beiler

Contents

ab im kopp:

off in the head

Aamen:

Amen

ach:

oh

aenti:

aunt

boppli:

baby or babies

daadi:

grandfather

daed:

dad

danki:

thanks

Die Botschaft:

a weekly newspaper serving Old Order Amish communities everywhere

dippy eggs:

eggs cooked over easy

Englisch:

a non-Amish person

es dutt mir leed:

I am sorry

fraa:

wife

gut:

good

gut-n-owed:

good evening

hatt:

hard

haus:

house

kaffi:

coffee

kapp:

prayer covering or cap

kinner:

children or grandchildren

lieb:

love

maed or maedel:

girl or girls

make wet:

rain

mamm:

mom

mammi:

grandmother

mei:

my

mudder:

mother

onkel:

uncle

Ordnung:

the written and unwritten rules of the Amish; the understood behavior by which the Amish are expected to live, passed down from generation to generation. Most Amish know the rules by heart.

Pennsylvania

Deitsch:

Pennsylvania German, the language most commonly used by the Amish

rumschpringe:

running around period when a teenager turns sixteen-years-old

schtinker:

irritable person

scrapple:

traditional dish containing leftover pieces of the pig mixed with cornmeal and flour

umgwehnlich:

unusual

ya:

yes

J

OSEPHINE

D

RONBERGER ADJUSTED HER DARK SUNGLASSES

as she stared at the faceless dolls on display. She lifted one to eye level then eased her way closer to Linda. Turning the figure about, she pretended to study it even though her eyes were on the seventeen-year-old Amish girl standing with two friends at the neighboring booth.

She inched closer, as if somehow just being near Linda would comfort her. Then she heard one of the girls talking in Pennsylvania

Deitsch

, the dialect most Amish speak and one she regularly heard at the farmer’s market. Josie pushed her glasses down on her nose and slowly turned to her left, feeling like the stalker she had become over the past few weeks. She drew in a deep breath and blew it out slowly.

Two of the girls were wearing dark green dresses with black aprons. Linda was clothed in a dress of the same style, but it was deep blue, and Josie instantly wondered if Linda’s eyes were still a sapphire color. All of them wore prayer coverings on their heads, as was expected. Not much had changed since the last time Josie had been in Lancaster County.

She watched one of the girls fondling a silver chain hanging on a rack filled with jewelry. Linda reached forward and removed a necklace, then held it up for the other girls to see. Again they spoke to each other in a language Josie didn’t understand.

Josie knew she was staring, so she forced herself to swivel forward, and once more she pretended to be interested in the doll with no face, staring hard into the plain white fabric. Until recently, that’s how Linda had looked in Josie’s mind.

She placed the doll back on the counter alongside the others, and then wiped sweaty palms on her blue jeans before taking two steps closer to the girls who were still ogling the necklaces. Jewelry wasn’t allowed in the Old Order Amish communities, but Josie knew enough about the Amish to know that girls of their age were in their

rumschpringe

, a running around period that begins at sixteen—a time when certain privileges are allowed up until baptism. Josie watched Linda hand the woman behind the counter the necklace. Then she reached into the pocket of her apron and pulled out her money.

Josie moved over to the rack of necklaces and glanced at the girls. Linda completed her purchase, then turned in Josie’s direction so one of her friends could clasp the necklace behind her neck. Josie stared at the small silver cross that hung from a silver chain, then she let her eyes veer upward and gazed at the pretty girl who stood before her now, with blue eyes, light-brown hair tucked beneath her cap, and a gentle smile.

“That’s lovely.” Josie’s words caught in her throat as she pointed to the necklace. Linda looked down at the silver cross and held it out with one hand so she could see it, then looked back up at Josie.

“

Danki

.” She quickly turned back toward her friends.

No, wait. Let me look at you a while longer

.

But she walked away, and Josie stared at the girls until they rounded the corner. She spun the rack full of necklaces until she found the cross on a silver chain like Linda’s.

“I’ll take that one,” she told the clerk as she pointed to the piece of jewelry. “And no need to put it in a bag.”

Josie handed the woman a twenty-dollar bill and waited for her change. She glanced at the Rolex on her left wrist. Then she unhooked the clasp of the necklace she was wearing, an anniversary present from Robert—an exquisite turquoise drop that he’d picked up while traveling in Europe for business. She dropped the necklace into her purse while the woman waited for Josie to accept her purchase.

“Thank you.” Josie lifted her shoulder-length hair, dyed a honey-blonde, and she hooked the tiny clasp behind her neck. The silver cross rested lightly against her chest, but it felt as heavy as the regret she’d carried for seventeen years.

Josie straightened the collar on her white blouse. She cradled the small cross in her hand and stared at it. There was a time when such a trinket would have symbolized the strong Catholic upbringing she’d had and her faith in God. But those days were behind her. Now the silver cross symbolized a bond with Linda.

Mary Ellen scurried around the kitchen in a rush to finish supper by five o’clock and wondered why her daughter wasn’t home to help prepare the meal. She knew Linda went to market with two friends, but she should have been back well before now. Abe and the boys would be hungry when they finished work for the day. Mary Ellen suspected they were done in the fields and milking the cows about now.

She glanced at the clock. Four thirty. A nice cross-breeze swept through the kitchen as she pulled a ham loaf from the oven, enough to gently blow loose strands of dark-brown-and-gray hair that had fallen from beneath her

kapp

. It was a tad warm for mid-May, but Mary Ellen couldn’t complain; she knew the sweltering summer heat would be on them soon enough. She placed the loaf on the table already set for five. Her potatoes were ready for mashing, and the barbequed string beans were keeping warm in the oven.

The clippety-clop of hooves let her know that Linda was home. Her daughter had been driving the buggy for nearly two years on her own, but Mary Ellen still felt a sense of relief each time Linda pulled into the driveway, especially when she was traveling to Bird-In-Hand, a high-traffic town frequented by the tourists.

“Hi,

Mamm

. Sorry I’m late.” The screen door slammed behind Linda as she entered the kitchen. Her daughter kicked off her shoes, walked to the refrigerator, and pulled out two jars of jam. “We lost track of the time.” Linda placed the glass containers on the table.

“The applesauce is in the bowl on the left.” Mary Ellen pointed toward the refrigerator, then began mashing her potatoes.

Linda walked back to the refrigerator to retrieve the applesauce, and Mary Ellen noticed a silver chain around her daughter’s neck, tucked beneath the front of her dress. She remembered buying a necklace when she was Linda’s age, during her own

rumschpringe

. No harm done.

“I see you purchased a necklace.” She stepped in front of Linda and gently pulled a silver cross from its hiding place. “This is very pretty.” Mary Ellen smiled before returning to her potatoes. “But I reckon it’d be best if you took it off before supper, no? Your

daed

knows there will be these kinds of purchases during

rumschpringe

, but I see no need to show it off in front of him.”

“But it’s only a necklace. That’s not so bad.” Linda reached around to the back of her neck, and within a few moments, she was holding the chain in her hand. “Do you know that Amos Dienner bought a car during his

rumschpringe

?” Linda’s brows raised in disbelief. “His folks know he has it, but they make him park it in the woods back behind their house.” She giggled. “I wonder what

Daed

would do if I came home with a car and parked it back behind our house?”

“I think you best not push your father that far. He has been real tolerant of the time you’ve spent with

Englisch

friends, riding in their cars, going to movies, and . . .” Mary Ellen sighed. “I shudder to think what else.”

“Want me to tell you what all we do in town?” Linda’s voice was mysterious, as if she held many secrets.

Mary Ellen pulled the string beans from the oven. “No. I don’t want to know.” She shook her head all the way to the table, then placed the casserole dish beside the ham loaf. “Be best I not know what you do with your friends during this time.”

“

Ach, Mamm

. We don’t do anything bad.” Linda walked to her mother and kissed her on the cheek. “I don’t even like the taste of beer.”

Mary Ellen turned to her daughter and slammed her hands to her hips. “Linda!”

Linda laughed. “

Mamm

! I’m jokin’ with you. I’ve never even

tried

beer.” She twisted her face into a momentary scowl, then headed toward the stairs. “I guess I’ll go put my new necklace away.”

Mary Ellen believed Linda. She trusted her eldest child, and she was thankful for the close relationship they shared. Linda’s adventurous spirit bubbled in her laugh and shone in her eyes, but she was respectful of her parents and the rules. If going to the movies and buying a necklace were the worst things her daughter did during this running around period, she’d thank God for that.