Poison (20 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“Ranjit lait gia tey kehan lagaa, mein theek naheeen. Usdi ghar wali, Lakhwinder ney ambulance nu phone keeta. Mein usdey maalish karnee chahee tey usdey theek hon dee ardas keetee. Oh meinu ehi kahee gia, meinu hath naa laao.”

It was Tuesday afternoon, September 17. In the east end station, Kevin Dhinsa listened to Surjit Khela, Ranjit Khela’s grandmother, recount what happened the night he died. He translated her words to English as Warren Korol typed on his laptop: “Ranjit lay down, said he wasn’t feeling

well. Lakhwinder, his wife, called an ambulance. I wanted to rub his body and pray to help him get better, he kept telling me not to touch his body or feet.... The ambulance came, put an oxygen mask on his face and took him away on a stretcher. Paviter also phoned Ranjit’s friend, I think his name is Sukhwinder. They came to the house just before the ambulance arrived.”

well. Lakhwinder, his wife, called an ambulance. I wanted to rub his body and pray to help him get better, he kept telling me not to touch his body or feet.... The ambulance came, put an oxygen mask on his face and took him away on a stretcher. Paviter also phoned Ranjit’s friend, I think his name is Sukhwinder. They came to the house just before the ambulance arrived.”

“Do you think this happened,” Dhinsa interjected in Punjabi, “because Ranjit ate something?”

“

Naheen, eh taan rab dee marjee hey

.” (“No. It is God’s will.”)

Naheen, eh taan rab dee marjee hey

.” (“No. It is God’s will.”)

This was the routine for all the interviews. Dhinsa asked questions that were typed on Korol’s laptop, the answer came back in Punjabi, Dhinsa translated. Then Dhinsa read the answer back to the witness in Punjabi for confirmation. That was how it went from interview number one with Surjit Khela, through interviews 10, 20, 60, 80, and more. A few of the people being questioned spoke English. Most did not.

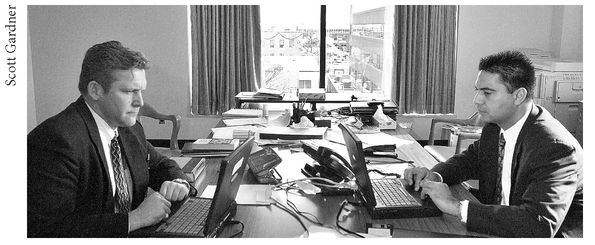

Korol and Dhinsa were different, and the same. They were both 36, but Korol had nearly 10 years more experience as a police officer. The roots of both their family trees were outside Canada, Dhinsa’s in India, Korol’s in Ukraine. Both men stood more than six feet, pushing over 200 pounds apiece, Korol with a thicker physique, Dhinsa slighter. Korol had the light brown-graying hair, Dhinsa’s black hair was cropped short. With his tanned, often serious face and dark eyes, Dhinsa radiated intensity. Korol came off easy-going. He was the lead investigator, but the pair were more like equals in the heat of the investigation. “Meet the brains of the operation,” was the way Korol eventually came to introduce his partner. “Indispensable.”

Detectives Warren Korol and Kevin Dhinsa

They finished interviewing Surjit, and then Ranjit’s grandfather, Piara. Why, the detectives asked Surjit, did Ranjit name Sukhwinder Dhillon the sole beneficiary of his life insurance policy?

“I don’t know,” Surjit said in Punjabi. “But we trust Jodha, he was like our own family. When Jodha went to India, my family would look after his house. Since Ranjit’s death, he drops in all the time. He takes us places.”

After Korol and Dhinsa finished they walked the elderly couple to the police station lobby. Waiting for them was Ranjit’s uncle, Paviter, and a man with a dark beard, short black hair, wide eyes, and a burly physique. Dhillon. Korol had seen his photo in the report of his assault on Parvesh. Grandfather Piara spoke Punjabi to both the uncle and Dhillon.

“

Police kehndee hey ki, Ranjit dee mot zehar naal hoee hey

.”

Police kehndee hey ki, Ranjit dee mot zehar naal hoee hey

.”

Dhillon’s eyes widened, as though he was surprised by what he was hearing.

“

Eh kiven hoea

?” Dhillon replied.

Eh kiven hoea

?” Dhillon replied.

The group of them left the station. Dhinsa turned to Korol.

“Warren. I overheard them.”

“And?”

“Piara told them that the police say poison killed Ranjit. Then the uncle repeated it to Dhillon. And Dhillon said, ‘Well, how did that happen?’”

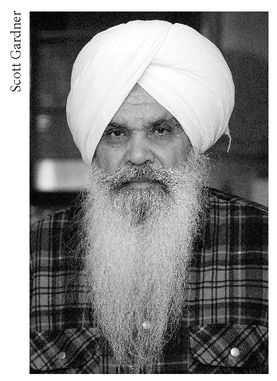

Piara, Ranjit Khela’s grandfather

Later that day, the detectives interviewed Lakhwinder, Ranjit’s widow. She talked about the dinner she served him, nothing out of the ordinary. She said little else, said nothing about Dhillon, or anyone else, giving Ranjit anything. There was no shortage of suspects as far as Korol was concerned. Ranjit’s family said Ranjit and Lakhwinder were going through a divorce. The pair may have had a difficult relationship. Lakhwinder was a suspect. So too were Ranjit’s grandparents,

who practiced homeopathic medicine. Did they give him strychnine, by accident or otherwise? Dhillon was, of course, the main suspect. Only he stood to gain financially from his friend’s death.

who practiced homeopathic medicine. Did they give him strychnine, by accident or otherwise? Dhillon was, of course, the main suspect. Only he stood to gain financially from his friend’s death.

The next day, Wednesday, Korol sat in front of a computer at the station. He planned to interview Lakhwinder’s brother, Udham Singh Sekhon, and Harmail Singh, Ranjit’s brother-in-law. Korol logged on to CPIC, the Canadian Police Information Computer. He usually did a check for any criminal record before each interview. He typed in the name Sekhon, Udham Singh, and his address in Hamilton. The computer spat out the information:

1. 92/01/08 DWI $400

2. 92/09/23 Driving with more than 80 mg of alcohol in the blood. Two charges, 21 days on each.

3. 94/07/25 Oakville: a) care or control while impaired, 3 months. b) driving while license disqualified, 1 month consec. c) driving while impaired, 3 months consecutive proh dri 3 years. d) driving while disqualified, 1 month consec and proh dri one year

4. 96/01/02, assault, susp sent and two years probation

Korol typed in Harmail Singh’s name. The first six counts were from Vancouver, the last two in Hamilton.

1. 1980: 80 mgs alcohol, 30 days

2. 1982: Impaired, 14 days

3. 1985: refuse breathalyzer, 3 months

4. Theft under $100

5. 1988: Impaired, fail to attend

6. 1988: Impaired, fail to attend

7. 1989: Assault, utter death threats

8. 1994: DWI, refuse sample

Neither man was an exemplary citizen, it appeared. But Korol didn’t discriminate when it came to getting information.

“Vistinduk, jahar, kuchila, vishtinduk, nux vomica.”

The naturopath listed Punjabi words for strychnine. “

Kuchila

comes from the kapilo tree, the leaves and berries are poisonous,” he continued. It was Thursday and Korol and Dhinsa were interviewing an east Indian naturopath in east Hamilton.

Kuchila

comes from the kapilo tree, the leaves and berries are poisonous,” he continued. It was Thursday and Korol and Dhinsa were interviewing an east Indian naturopath in east Hamilton.

“Could you mask it?” Korol asked.

“To an extent.

Kuchila

has no odor if mixed with alcohol or spices like ginger. But it is very bitter tasting.” He added that when

kuchila

is diluted, it does have healing powers. People use it as a pain killer, or for stiffness, mental sharpness. Impotency, too. But in its pure form, it kills. “Once in the bloodstream, to the central nervous system, the body spasms. Convulsions, muscles contract, blood pressure increases and the heart rate quickens until the heart fails.”

Kuchila

has no odor if mixed with alcohol or spices like ginger. But it is very bitter tasting.” He added that when

kuchila

is diluted, it does have healing powers. People use it as a pain killer, or for stiffness, mental sharpness. Impotency, too. But in its pure form, it kills. “Once in the bloodstream, to the central nervous system, the body spasms. Convulsions, muscles contract, blood pressure increases and the heart rate quickens until the heart fails.”

The naturopath knew nothing of the homicide investigation, but he had just described perfectly the symptoms exhibited by Ranjit and Parvesh shortly before they died.

“Thank you,” Korol said. “I’ll be in touch if we need anything more.”

Next the detectives interviewed Billo, Lakhwinder’s brother. He reconstructed his view of the last evening he’d seen Ranjit, on June 23. Billo had purchased a used Dodge Caravan van from Ranjit on June 23 for $6,500. That same day he, Ranjit, and Jodha drove it to a government office to get it certified. At 4:30 in the afternoon they returned to the Khela home on Gainsborough Road.

“Billo, you just bought a new van,” Ranjit said. “You should party. We should get some drinks.”

“What for? You don’t even drink, Ranna.”

“So what? Paviter is home, he’ll help you drink.”

At 6 p.m., the three men drove to buy whisky at a liquor store in the mall. Billo and Dhillon downed shots in the parking lot. Then Ranjit drove them back to his house on Gainsborough. Paviter came out to join them. Ranjit didn’t drink, but the other three men sat in the van in the driveway, swigging from the bottle. Ranjit went into the house and came back out with some food

on a plate. Then he left the others to go visit his grandmother in hospital. Ranjit returned to the house at 9:30 p.m. to find Dhillon, Billo, and Paviter still sitting in the van, drinking and talking.

on a plate. Then he left the others to go visit his grandmother in hospital. Ranjit returned to the house at 9:30 p.m. to find Dhillon, Billo, and Paviter still sitting in the van, drinking and talking.

“Ranna, how about some more food?” Billo said. Ranjit shook his head.

“Come on, join us! Join us for some drinks!”

Soon afterwards, Ranjit drove Dhillon home. He offered to drive Billo home, too. “I’m just around the corner, I’m fine to drive,” Billo replied, whisky on his breath. Billo drove off in his new van, but Ranjit followed him to make sure he got home safe. Ranjit phoned Billo’s wife later, about 10 p.m., to make sure he was okay.

Korol’s laptop clicked as Dhinsa translated the story. By Billo’s account, Dhillon definitely had time alone with Ranjit. Was Billo telling it straight? He did admit to driving home while probably impaired. Given his record, he was probably telling the truth about that. He had offered a glimpse into the complicated issues within the Khela family. The divorce Ranjit and Lakhwinder were supposedly going through was “only on paper,” a sham, he said, so each could marry another Indian and bring them to Canada. There was a custody dispute over their boy, who was named Ranjod.

“Lakhwinder, my sister, is a timid woman, she does what elders tell her,” Billo said. “Some people wonder if the poison was meant for my sister and Ranjit took it by accident. Ranjit’s father wants custody of Lakhwinder’s son.”

Dhinsa asked if there was anything else Billo could tell them about Ranjit’s death.

“

Eh taan rab dee marjee hey

.”

Eh taan rab dee marjee hey

.”

“It is God’s will,” Dhinsa repeated for Korol. God’s will—that was the second time the detectives heard the phrase in relation to Ranjit’s death. It would not be the last. Outside the Khela home that same day, Thursday, Piara, Ranjit’s grandfather, told the detectives he didn’t believe Ranjit was murdered. Korol was amazed. He was learning about Sikh belief in fate, but he also wanted to give the old man a wake-up call.

“Kevin,” Korol said to Dhinsa, “tell the grandfather the toxicologists found poison in Ranjit’s blood, and that someone put

it there. Tell him about the autopsy, the whole process. Give it to him straight.”

it there. Tell him about the autopsy, the whole process. Give it to him straight.”

Dhinsa spoke, and Piara’s face tightened. Then the old man broke down and cried.

On October 8, the detectives pulled up in front of an apartment building on Grandville Avenue, in the neighborhood where Dhillon lived. There they spoke with a man named Yog Raj Rathour, an insurance agent and respected member of the Indian community whom Ranjit had dealt with when he first came to Canada. Ranjit had once purchased a life insurance policy through Yog, but had canceled it without explanation a few weeks before he died.

Other books

Loop by Koji Suzuki, Glynne Walley

Impávido by Jack Campbell

A Knight's Reward by Catherine Kean

An Invisible Client by Victor Methos

Faithless by Bennett, Amanda

Protective Instinct by Katie Reus

Twisted Innocence (Moonlighters Series Book 3) by Blackstock, Terri

Monkey Business by Leslie Margolis

Last Tales by Isak Dinesen

Private Pleasures by Jami Alden