Poison (21 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Yog told the police about bizarre rumors floating within the community. Ranjit had a friend named Jodha. Yog himself had never met him. Jodha’s wife died suddenly last year. She had a stiff back, a painful grimace on her face. Very strange. Then Jodha went to India. They say he married several women, received dowry money. And one of the women died a death similar to Jodha’s first wife. It was all just rumors, some of it came all the way from India, and who knows how it got twisted or who was trying to get at Jodha. Korol looked at Dhinsa. They knew that Jodha was Sukhwinder Dhillon’s nickname. Korol’s thoughts raced. The trail might lead to India. He and Dhinsa could be taking a trip.

It was time to interview Dhillon himself. Korol wanted to keep the questions confined to Ranjit’s death. Don’t let Dhillon know they have him in their sights for Parvesh’s murder, or that they have heard rumors about a possible India connection. Korol punched in the number on his cellphone.

“Mr. Dhillon. This is Detective Sergeant Warren Korol of Hamilton police. Detective Kevin Dhinsa and I plan to drop by your house for an interview.”

“Yes, yes, yes—don’t speak much English,” Dhillon replied.

“That’s fine,” Korol said. “Detective Dhinsa speaks Punjabi.”

The detectives drove along Barton Street, past Aman Auto, Dhillon’s car dealership, then onto Berkindale Drive and pulled up in front of number 362. Dhillon answered the door.

“I’m Detective Warren Korol. This is Detective Kevin Dhinsa.”

Dhillon smiled and shook their hands vigorously.

“Yes, hello, come in, come in,” he said.

They sat in the kitchen and Korol hooked up his laptop. Dhillon spoke excitedly.

“Anything I can do, anything, fine, fine.”

His English was fast and rough, and he lapsed back and forth between bursts of English and Punjabi. Dhillon pulled a long tube from a shelf, removed a roll of paper from inside and unfurled it on the table. It was a blueprint for a new garage he was going to build on the house. After showing it off, Dhillon sat down.

“You can ask me anything,” Dhillon said, smiling. Dhinsa began, in Punjabi.

“Have you ever heard of strychnine, also known as

vistinduk

,

kuchila

,

jahar

,

kuchola

,

vishtinduk

, or

nux vomica

?”

vistinduk

,

kuchila

,

jahar

,

kuchola

,

vishtinduk

, or

nux vomica

?”

“I’ve never heard of them,” Dhillon said. “I’m not an educated man. I have only heard of these names from you. I went to school three or four years. I’m just a dairy farmer.”

“Can you tell us how this poison might have got into Ranjit’s body?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know if he had any problems in the house, don’t know if there was any fighting. I never saw anything.”

“On your dairy farm, do you or your servants give anything to the animals to help them reproduce or enhance fertility?”

“No. We didn’t give them anything. Just grain.”

Dhillon talked of the last day he spent with Ranjit. He said Billo, Ranna, and he all went to register the car at 2 p.m., then to the liquor store. They returned to Ranjit’s house, then he, Dhillon, went home alone. His story did not mesh with Billo’s, who said Ranjit drove Dhillon home. Korol jumped in.

“What time did you leave Ranjit’s home after returning from the liquor store?”

“Around two or three,” Dhillon said in English. “I usually have one or two shots then slip out. Billo starts talking nonsense when he has a few drinks.”

“How could you have left Ranjit’s home at two or three ’o’clock to go home when you already said it was two when Ranjit and Billo picked you up to go to the ministry?”

“They weren’t very long in the ministry. It couldn’t have been more than two-thirty, three.”

“After you returned from Ranjit’s house, did you see him again that day?”

“No, I didn’t. I was working in my garden, planting.”

“How was the death of Ranjit explained to you?”

“I don’t know, I don’t speak much English,” Dhillon said.

Dhinsa finished with the final statement they gave all the witnesses: “We are sorry about the death of Ranjit Khela. It is important that we investigate this case thoroughly to find out how the poison got into his body. Is there anything we can do for you at this time?”

“I don’t know anything about it,” Dhillon replied. “I am just a simple

jat

man.”

jat

man.”

CHAPTER 11

LIE DETECTOR

On Wednesday, October 23, Korol started chasing the India connection. He visited the Canadian immigration office on King Street and asked an official named Paul Bassi to dig for information on Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon. Bassi produced a document.

“Mr. Dhillon filled out two applications to sponsor two different females to enter Canada as his wife,” Bassi said.

The blue eyes narrowed.

“The first was for a Kushpreet Kaur Dhillon, made on November 2, 1995. The second was for a Sukhwinder Kaur Dhillon, made on April 15, 1996. Neither woman has ever landed in Canada.”

Korol hurried back to Central Station and began drafting a letter to Interpol in India, requesting information on the possible deaths of the two women and, if they were dead, the cause of death. He sent it the next morning. Then Korol phoned a contact with the RCMP, who put him in touch with Pierre Carrier, a liaison officer with the Canadian High Commission in New Delhi.

“Things happen pretty slow around here with the Indian authorities,” Carrier told Korol. “And rumors fly all the time. But we’ll do what we can.”

A week later, on Thursday, October 31, Korol and Dhinsa visited Ranjit’s family on Gainsborough Road again.

“Stop bothering us,” Ranjit’s grandfather, Piara, told Dhinsa in Punjabi. Dhinsa said nothing. “I want you to guarantee,” Piara continued, “that if any of us should die because of our cooperation with police, you will bear full responsibility.”

Later that afternoon a fax arrived from New Delhi. Pierre Carrier confirmed some interesting information about Dhillon. Sukhwinder Dhillon married a Sarabjit Kaur Brar on April 5, 1995, in India. They had two children. There is now a petition for divorce. Dhillon married a Kushpreet Kaur Toor on April 30, 1995, in India. She died in her village on January 23, 1996, of a heart attack. Dhillon married Sukhwinder Kaur Dhillon on February 16, 1996, and is sponsoring her to come to Canada but she has been refused entry by Canadian immigration authorities due to the number and timing of the marriages.

Korol had barely finished the fax when he grabbed the phone and called New Delhi, where the time was 10 hours ahead.

“Pierre?”

Carrier answered the phone at home, in bed, then took the call in his kitchen.

“What can I do for you, Warren?”

“Sorry about the hour, Pierre,” Korol said. “But I had to confirm—is the information on this report legit?” Carrier replied that the facts were correct. Korol asked for copies of any documents about Dhillon.

“And Pierre, don’t start asking questions about Kushpreet in India. I want to get Dhillon in for a polygraph first, and I don’t want word getting back to him that we know what he’s been up to over there.”

The air was thick with moisture and the smell of cedar. Beads of water formed on Sukhwinder Dhillon’s shoulders.

“

Bhara, mein kujh naheen keeta. Mein kujh vee galat naheen keeta

.” (Brother, I didn’t do it. I didn’t do anything wrong.) Dhillon sat on the bench in the sauna with his friend, Kalwinder Singh, at Family Fitness Center on Barton Street. Kalwinder looked over at Dhillon, who sat with his elbows on his knees, his paunch straining forward. The friends rarely talked about family. It was always business. But not this time. Kalwinder had already heard the rumors at the temple. The police were after Dhillon, accusing him of killing his wife and his business friend. He married a bunch of women in India, probably killed there, too. Kalwinder didn’t know what to believe. Dhillon seemed so sincere in his manner. And he was a good guy. Kalwinder said nothing to get him going on the rumors. Dhillon had just started talking.

Bhara, mein kujh naheen keeta. Mein kujh vee galat naheen keeta

.” (Brother, I didn’t do it. I didn’t do anything wrong.) Dhillon sat on the bench in the sauna with his friend, Kalwinder Singh, at Family Fitness Center on Barton Street. Kalwinder looked over at Dhillon, who sat with his elbows on his knees, his paunch straining forward. The friends rarely talked about family. It was always business. But not this time. Kalwinder had already heard the rumors at the temple. The police were after Dhillon, accusing him of killing his wife and his business friend. He married a bunch of women in India, probably killed there, too. Kalwinder didn’t know what to believe. Dhillon seemed so sincere in his manner. And he was a good guy. Kalwinder said nothing to get him going on the rumors. Dhillon had just started talking.

“They say I got the woman pregnant,” Dhillon said. “It’s not true. I’m all clear on that. It was someone else. And the dead babies, they were dead at birth.” Kalwinder said nothing. Dhillon continued. “I don’t know why everyone is saying this about me. I am innocent. They think I killed Ranna, too. I didn’t do anything,

I’m telling you.” They left the gym. A few weeks later, Dhillon pulled up in front of the truck repair shop his friend owned.

I’m telling you.” They left the gym. A few weeks later, Dhillon pulled up in front of the truck repair shop his friend owned.

“Brother!” Dhillon said.

Kalwinder grinned.

“Jodha.”

Kalwinder figured the police were getting closer to Dhillon. He even believed that a cop had been in the sauna with the two of them on at least one occasion, a white guy, listening to their conversation. But Dhillon hardly seemed concerned by the attention.

“How are things?” Kalwinder said.

“There’s a cop over there,” Dhillon replied, gesturing to a vehicle parked down the street. “He’s following me.” Dhillon kept a straight face, then broke into a grin and laughed. One of Kalwinder’s workers walked over. He liked Dhillon. Thought he was a good guy.

“Hey Jodha, if you were in India, whether you did it or not, if they thought you did it you’d be in jail already.”

Dhillon nodded in agreement. His brother, Sukhbir, had been a cop in India. And his father, too. Jodha, he knew all about cops. Was friendly with the Hamilton cops here, too, especially the Indian guy, Dhinsa.

“In India you’d be in jail,” the worker repeated, “and if you weren’t in jail, they’d beat you. They’d say, ‘Did you do it?’ And if you said no, they’d beat you. They’d say, ‘Did you do it?’ And if you said no, they’d beat you until you said yes.”

Dhillon nodded and laughed. The worker shook his head, grinning. “Here, they can’t touch you! They’re not allowed to.”

“You’re right,” Dhillon said. “You’re right.”

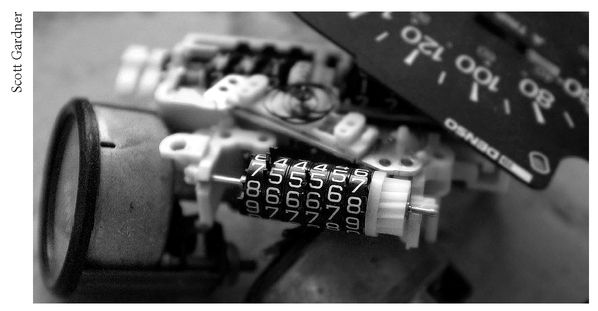

Police surveillance on Dhillon continued through the fall. One afternoon, Dhillon left his house carrying a brown paper bag. He drove to Eastgate Square mall and entered carrying the bag, its bottom straining from the weight of what was inside. How many cars had he sold with a bogus mileage reading? He approached a garbage can in the food court and stuffed the bag in, then turned and left. A couple of minutes later, a hand reached into the garbage can, retrieved the paper bag, and pulled it out. The undercover Hamilton police officer opened the bag and peered inside. There

were several of them, metal cylinders. The cop walked out of the mall, got into his unmarked car, and drove back to the station. You’ll never guess what Dhillon dropped in a garbage pail at the mall, he reported. Odometers. A whole bag of them.

were several of them, metal cylinders. The cop walked out of the mall, got into his unmarked car, and drove back to the station. You’ll never guess what Dhillon dropped in a garbage pail at the mall, he reported. Odometers. A whole bag of them.

Police found a bag of odometers that Dhillon had tossed in the garbage.

On Wednesday, November 13, Korol and Dhinsa again paid a visit to Dhillon’s home. Korol wanted to get him to agree to take a lie detector test. The three men sat at his kitchen table. Dhillon stood up, opened the fridge, and turned to Dhinsa. Speaking Punjabi, he asked Dhinsa a question. Dhinsa shook his head no. Korol smirked. “Dhillon, we know you can speak English,” he said. “We found out that you helped the Khela family as a translator in the past. You should also know that the polygraph test will go much quicker if you speak English.”

Other books

The Dwarfs by Harold Pinter

El vendedor más grande del mundo by Og Mandino

Sleep with the Fishes by Brian M. Wiprud

Brightling by Rebecca Lisle

THE ORANGE MOON AFFAIR by AFN CLARKE

Wolf at the Door by Sadie Hart

Nerd Girl by Lee, Sue

From Cape Town with Love by Blair Underwood, Tananarive Due, Steven Barnes

Roman's Redemption: Roman: Book II (Roman's Trilogy) by Dawn, Kimber S.