Poison (15 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Ranjit awoke on Saturday morning, June 22, filled with anticipation. That day a jet carrying his parents and his sister Karmajit had taken off from India. They were coming to visit him in Canada. And he was closing a deal to sell a car. That afternoon he sold his brother-in-law, Udham “Billo” Sekhon, a Dodge Caravan for $6,500. Dhillon was there. The three of them drove the minivan to the Ministry of Transportation to register the purchase. Time to celebrate. They stopped at the liquor store in Queenston Mall, picked up a twenty-sixer of Crown Royal whisky, returned to Ranjit’s place on Gainsborough Road. Ranjit rarely drank. Dhillon and Billo took turns on the bottle inside the van as it sat parked in the driveway.

Later that evening, Ranjit offered to drive Jodha home. It was only a few minutes’ drive. Dhillon brought it up again, Ranna’s impotence problem. He had just the remedy. Dhillon had the pill with him. He showed it to Ranjit. It was a capsule. Miracle medicine. Think about it, Ranna. In bed you will last much longer. Amazing. If anyone knows about performance with women—much younger women—it’s Jodha! All those women in India, sex every day.

Ranjit said good night to Dhillon and drove back to his house, alone. That night, a late dinner. Lakhwinder served Ranjit and the family vegetables with ginger, roti bread, yogurt. Afterward Ranjit spoke upstairs with his grandmother, Surjit, then went downstairs to the area he shared with Lakhwinder. She waited for him in the bedroom, where she had tucked in their two-year-old boy, Ranjoda. After Ranjit showered he walked across the hall into the bedroom. Incense burned on top of the dresser.

The bed he shared with Lakhwinder was a mattress and some sheets on the floor. He slipped in beside her. How long had it been since he took the medicine? He felt—odd. And vigorous. The erection, yes, but more than that, his other muscles felt hard, blood pumping through them. Jodha was right. He could go all night. They had sex, then lay on the bed side by side. But Ranjit was still erect. Something did not feel right. All his muscles felt as if they were contracting against his will. The touch of the sheets felt like needles on his skin. He put on his underwear.

“Ranjit, what’s wrong?” Lakhwinder asked.

“I don’t know—don’t touch me,” Ranjit said, then yanked the sheets away from his skin as though they were on fire. Minutes later, he was convulsing, muscles clenching spastically. Somebody phoned 911 at two minutes after midnight. And then Paviter Khela, Ranjit’s uncle, phoned Dhillon. Ranna is very sick. What did Jodha give him? “He had nothing at my house. I gave him nothing,” Dhillon replied. “I’ll come over.”

Paramedics Timothy Dault and Peter Morgan were sitting in an ambulance at Barton and Kenilworth when the emergency call came in. “Emergency. Eighty-eight Gainsborough Road.” The dispatcher had the wrong house number, perhaps because of a language barrier over the phone. They arrived at the correct address at 12:16 Sunday morning. They carried the stretcher inside, were shown to the basement. Incense in the air, family members, as many as 10 of them, shouting, wailing, chaos. On the bed lay Ranjit Khela, 25, in his underwear, his penis still erect. Drenched in sweat, drooling. Muffled sounds from the back of his throat. He seemed euphoric, talking to himself, his teeth clenched so tightly the gums bled, lips drawn back in a bizarre grimace.

Dhillon arrived at the house. In the kitchen upstairs, the Khelas confronted him. What did you give Ranna? “I didn’t give him anything,” he said. “I didn’t do anything.”

The paramedics fired questions at the family. Dhillon acted as translator. He was the only one who spoke any English. “He ate dinner, and felt fine,” Dhillon told Dault and Morgan. “Nobody knows what happened.” The paramedics strapped Ranjit onto the stretcher and loaded him into the ambulance and sped to Hamilton General Hospital. He lapsed in and out of consciousness.

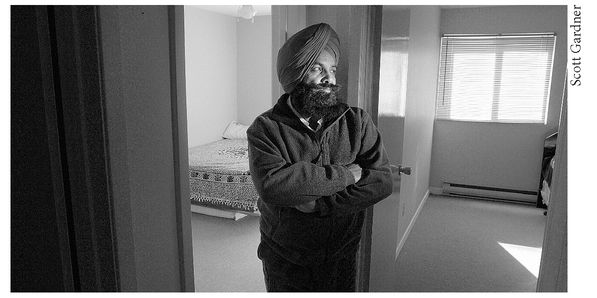

Makhan Khela was on his way to visit from India when his son, Ranjit, died.

Strychnine—

kuchila

—rapes the nervous system, sends signals from the brain that strangle muscles, but worst of all, leaves the victim aware of what is happening. At the end, Ranjit called out briefly in Punjabi. He was declared dead at 2:03 a.m. Paviter, his uncle, knelt on the floor, crying. “If I had a gun,” he cried, “I’d shoot myself and then I could be with him.”

kuchila

—rapes the nervous system, sends signals from the brain that strangle muscles, but worst of all, leaves the victim aware of what is happening. At the end, Ranjit called out briefly in Punjabi. He was declared dead at 2:03 a.m. Paviter, his uncle, knelt on the floor, crying. “If I had a gun,” he cried, “I’d shoot myself and then I could be with him.”

Dhillon was there with the weeping family, his face creased in sorrow. He put his thick hand on Paviter’s shoulder and helped him to his feet.

“God’s will,” Dhillon said. “We can’t understand it.”

The sudden, unexplained death of a young adult meant a call to the coroner. Dr. Bashir Khambalia received the call to visit the morgue at Hamilton General Hospital to examine the body and charts. The deceased was a Sikh man named Ranjit Khela. It is not known whether the coroner read the notes on Ranjit written by those who had treated him. A coroner has access to such notes, but is not required to consult them. It was another sudden death of a seemingly healthy young Indian who lived in the Riverdale neighborhood of east Hamilton. Once again, the deceased was stricken by seizures, muscle spasms, the sickly grimace, oxygen shut-off to the brain. Khambalia had also handled the mysterious death of Parvesh Dhillon 17 months earlier.

He did not order toxicology testing from the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto. That was an option open to him, but was not required. Khambalia ordered an autopsy. He did not phone police. He would have done that only if he suspected something.

CHAPTER 8

AN IMPOSSIBLE CASE

The funeral for Ranjit Khela was held July 6. His cremated ashes were taken back to India by his grandparents. Dhillon was at the funeral in Hamilton. At the visitation, he was overheard telling someone next to him to keep a distance from the body: “Be careful, stand back, there might be harmful gas coming from it.” The family friend looked at Dhillon, puzzled. What does that mean? At the Khela home, friends and members of the Sikh community dropped by to express condolences. They spoke with Lakhwinder, who was still devastated and had wept through the entire service. A friend of Dhillon’s named Mangat and a few others walked up to her.

“What happened that night?” Mangat asked. Lakhwinder had kept the secret to herself. Her husband’s dying words were too dangerous to reveal. And Ranjit was gone, there was no changing that. But still, she spoke out. “Ranna told me just a few minutes before that he had taken a pill,” Lakhwinder said.

“A pill? What kind?”

“He didn’t say. He took a pill at Jodha’s house.”

Dhillon stood to the side, listening.

“No, Ranna ate nothing at my house,” he said.

“He—he must have been joking,” Lakhwinder said.

Silence filled the room.

Dhillon quickly applied for Ranjit’s life insurance benefits. It was time for Ranna’s “uncle” to close the deal. The first week in July, Sunoco asked Dhillon about finalizing his purchase of the vacant Barton Street property where he intended to expand his used-car dealership. He still didn’t have the money. Just needed more time. He signed a second delay agreement, to July 30. And then, on July 25, Dhillon asked a local builder for an estimate on designing and building a new garage on the land. He was quoted a price of $89,000. Five days later, on July 30, Dhillon signed a new contract with Sunoco, delaying the sale to the end of August. His money was on the way. Dhillon was unstoppable.

It sits like a mirage in Agra, two hours south of New Delhi, a shimmering white beacon in the sun’s harsh light at high noon; a textured, sparkling ivory colossus in the moonlight. It took 20 years to build the Taj Mahal—20,000 workers, starting in 1631, with no modern engineering technology. Yet what they built is miraculously exact, windows lined up perfectly, all of it precisely symmetrical as though designed by the hand of God. It is an architectural wonder. It is perfect. Almost. The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan ordered the Taj Mahal built as a tomb for his dead wife. It was a brash act. He succeeded. But then he ordered a second mausoleum, a black one, to be built across the Yamuna River from the original to house his own body. This act of egotism prompted his son to throw the emperor in jail for the remainder of his life to stop him bankrupting the country. And so the second tomb was never completed. When the emperor died, he was entombed beside his wife in the original Taj Mahal. But this second crypt destroyed the symmetry of his ethereal creation, which was designed to hold one body. The second crypt—for the emperor who went too far—is the Taj Mahal’s one glaring flaw.

Central Station

Hamilton Police Service

August 13, 1996

Hamilton Police Service

August 13, 1996

Tuesday morning, August 13, 1996, dawned hot. The unraveling began so slowly as to be imperceptible, with a phone ringing.

“Sergeant McCulloch.”

The uniformed cop’s voice carried a Scottish brogue which instantly cast him as a seasoned veteran, as though his life was defined by knocking heads with toughs, maybe walking a foggy beat with a billy club years ago. In the case of David McCulloch, who was nearing retirement and worked in the Hamilton police coroner’s department, that was in fact pretty much true.

He was raised in a Scottish village called Elderslie, his house a brief sprint from the monument marking the birthplace of

Braveheart, national hero William Wallace. McCulloch was born on September 3, 1939, the day Britain and France declared war on Hitler. His earliest memory was being snug in his mother’s arms, peering up at a blue-black sky flecked with dots of white light, the beams searching for Luftwaffe bombers. In his adult life McCulloch had once walked the beat unarmed in London, though he used the club a few times. The Scot had met his share of nasty characters in his 30 years on the Hamilton force, too. He once rode in the courthouse prisoner’s elevator beside a six-foot, 230-pound repeat child molester named James Clayton Collier, whom he had helped catch. A brilliant 34-year-old Hamilton Crown prosecutor named Brent Bentham sent Collier to federal prison for an indefinite sentence wearing the city’s first dangerous-offender tag.

Braveheart, national hero William Wallace. McCulloch was born on September 3, 1939, the day Britain and France declared war on Hitler. His earliest memory was being snug in his mother’s arms, peering up at a blue-black sky flecked with dots of white light, the beams searching for Luftwaffe bombers. In his adult life McCulloch had once walked the beat unarmed in London, though he used the club a few times. The Scot had met his share of nasty characters in his 30 years on the Hamilton force, too. He once rode in the courthouse prisoner’s elevator beside a six-foot, 230-pound repeat child molester named James Clayton Collier, whom he had helped catch. A brilliant 34-year-old Hamilton Crown prosecutor named Brent Bentham sent Collier to federal prison for an indefinite sentence wearing the city’s first dangerous-offender tag.

Other books

America's Galactic Foreign Legion - Book 22: Blue Powder War by Walter Knight

Surrender by Rhiannon Paille

Harvard Hottie by Costa, Annabelle

A Broken Us (London Lover Series Book 1) by Amy Daws

Behind Closed Doors by Sherri Hayes

Giants (A Distant Eden Book 6) by Tackitt, Lloyd

Kilenya Series Books One, Two, and Three by Andrea Pearson

Florida Heatwave by Michael Lister

The Vampire Stalker by Allison van Diepen

Demon Butchers Zombie Horde by Dawn Harshaw